We all know it, the bright yellow poster with a strong woman in work clothes and cute red scarf, encouraging her fellow ladies to join her in the war effort , because “They Can Do It” and they could do it and did it, but not thanks to this poster.

For years the “We can do it poster” colloquially known as Rosie the Riveter has served and still does as an iconic symbol of strength, motivation, and is closely connected with feminism.

The poster is so popular nowadays that gives an impression that it single-handedly inspired the phenomenon of “Rosie the Riveters ” and motivated all the housewives during WWII. Well, one may think this, but one would be very wrong.

The poster that we all love so much, was not popular at all during World War II, as a matter of fact, it was hardly seen. The poster rose to fame, years after the war was over, more specifically in the early 1980s. This is what actually happened.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the US government called upon manufacturers to produce greater amounts of war goods. The workplace atmosphere at large factories was often tense because of resentment built up between management and labor unions throughout the 1930s. Directors of companies such as General Motors (GM) sought to minimize past friction and encourage teamwork.

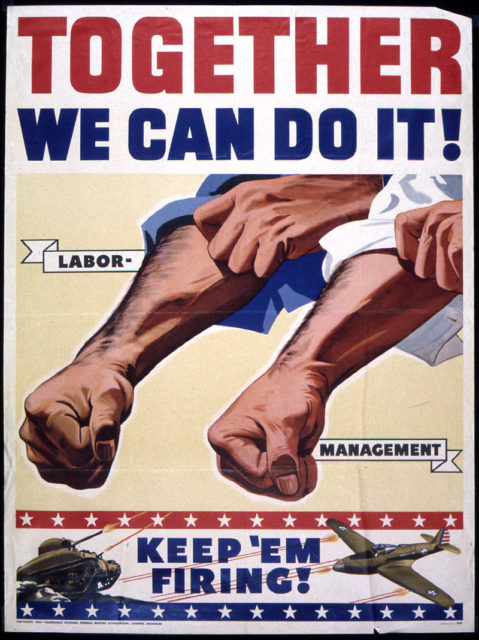

In response to a rumored public relations campaign by the United Auto Workers union, GM quickly produced a propaganda poster in 1942 showing both labor and management rolling up their sleeves, aligned toward maintaining a steady rate of war production.

The poster read, “Together We Can Do It!” and “Keep ‘Em Firing!” In creating such posters, corporations wished to increase production by tapping into the popular pro-war sentiment, with the ultimate goal of preventing the government from exerting greater control over production.

In 1942, Westinghouse Electric’s internal War Production Coordinating Committee hired the Pittsburgh artist J. Howard Miller through an advertising agency, to create a series of posters to display to the company’s workers.

The intent of the poster project was to raise worker morale, to reduce absenteeism, to direct workers’ questions to management, and to lower the likelihood of labor unrest or a factory strike. Each of the more than 42 posters designed by Miller were displayed in the factory for two weeks, then replaced by the next one in the series. Among all the “men” posters emphasizing traditional roles for men and women, was the yellow poster with a strong female figure with the words “We Can Do it.”

So that was it, the poster was strictly internal to Westinghouse displayed only during February 1943, and was not even intended to inspire women to join her but to exhort already-hired women to work harder. The war was over, women got back to being housewives and men got back in the factories. The poster along with other war ephemera found its place somewhere in the National Archives.

Years after, in 1982, the “We Can Do It!” image was reproduced in a magazine article, “Poster Art for Patriotism’s Sake”, a Washington Post Magazine article about posters in the collection of the National Archives. From then on, feminists and others have seized upon the uplifting attitude and apparent message to remake the image into many different forms, including self-empowerment, campaign promotion, advertising, and parodies.

The poster served and still serves as an advocate for women’s rights in the workforce. In 1984, former war worker Geraldine Hoff Doyle came across an article in Modern Maturity magazine which showed a wartime photograph of a young woman working at a lathe, and she assumed that the photograph was taken of her in mid-to-late 1942 when she was working briefly in a factory. Ten years later, Doyle saw the “We Can Do It!” poster on the front of the Smithsonian magazine and assumed the poster was an image of herself. Without intending to profit from the connection, Doyle decided that the 1942 wartime photograph had inspired Miller to create the poster, making Doyle herself the model for the poster.

Subsequently, Doyle was widely credited as the inspiration for Miller’s poster. From an archive of Acme News photographs, Professor James J. Kimble obtained the original photographic print, including its yellowed caption identifying the woman as Naomi Parker. The photo is one of a series of photographs taken at Naval Air Station Alameda in California, showing Parker and her sister working at their war jobs during March 1942.

These images were published in various newspapers and magazines beginning in April 1942, during a time when Doyle was still attending high school in Michigan. In February 2015, Kimble interviewed the Parker sisters, now named Naomi Fern Fraley, 93, and her sister Ada Wyn Morford, 91, and found that they had known for five years about the incorrect identification of the photo, and had been rebuffed in their attempt to correct the historical record.

Although many publications have repeated Doyle’s unsupported assertion that the wartime photograph inspired Miller’s poster, Westinghouse historian Charles A. Ruch, a Pittsburgh resident who had been friends with J. Howard Miller, said that Miller was not in the habit of working from photographs, but rather live models. Penny Coleman, the author of Rosie the Riveter: Women working on the home front in World War II, said that she and Ruch could not determine whether the wartime photo had appeared in any of the periodicals that Miller would have seen

After she saw the Smithsonian cover image in 1994, Geraldine Hoff Doyle said that she was the subject of the poster. Doyle thought that she had also been captured in a wartime photograph of a woman factory worker, and she innocently assumed that this photo inspired Miller’s poster. Conflating her as “Rosie the Riveter”, Doyle was honored by many organizations including the Michigan Women’s Historical Center and Hall of Fame. However, in 2015, the woman in the wartime photograph was identified as 20-year-old Naomi Parker, working in early 1942 before Doyle had graduated high school. Doyle’s notion that the photograph inspired the poster cannot be proved or disproved, so first Doyle and then Parker cannot be confirmed as the model for “We Can Do It!”

Another myth connected to the iconic poster if not biggest, is the association with Rosie the Riveter. The poster does not have anything in common with Rosie the Riveter.

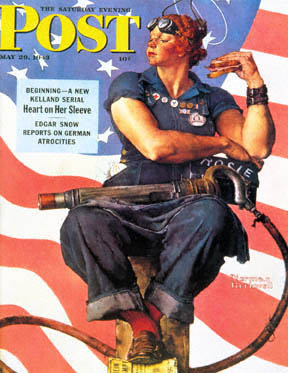

The real Rosie the Riveter poster was created by Norman Rockwell, featuring a chubby woman, taking her lunch break with a rivet gun on her lap and a lunch box beside her that reads “Rosie”.”; viewers quickly recognized this to be “Rosie the Riveter” from the familiar song.

So, that’s it. Don’t shot the messenger for “bursting the bubble”. Don’t get us wrong, we love this poster and what the poster represents, but we thought it would be a good idea to reveal the true behind it and free it from all the misconceptions and sensationalism related to it because “We can do it”