Ramesses II was one of the most powerful rulers of Ancient Egypt. He reigned in the 12th century B.C. for approximately 66 years, which was an unusually long time for a pharaoh, as the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

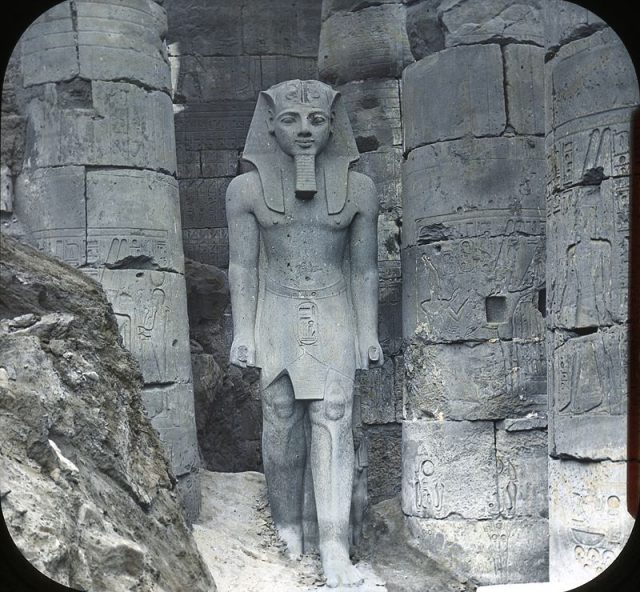

Egyptologists of the 19th century nicknamed him “Ramesses the Great” after they discovered that numerous archaeological sites across modern-day Egypt, Sudan, and Palestine contained monuments, temples, palaces, and shrines built in his honor. One of the most impressive structures built under Ramesses is the Ramesseum, a monumental memorial temple which still stands within the vast Theban necropolis.

The nickname “Great” was apparently well-deserved, as historical sources prove that the mighty pharaoh governed Egypt at a time of abundance, prosperity, and military conquests. His father, Pharaoh Seti I, known as Ramesses I, came from a non-royal family and took the throne some time after the demise of Akhenaten, a pharaoh who attempted to convert Egyptians to a newly-introduced monotheistic religion. Seti I made his son a military general when little Ramesses was merely 10 years old and appointed him Prince Regent when he was 14. The young prince then received extensive military training and was also given control over his own harem.

Contemporary historians are unsure at what age Ramesses inherited the throne from his father, but he likely became king in his early twenties. During his reign, he led several successful military campaigns to Syiria and Nubia (modern-day Sudan): his soldierly conduct and populist reforms made him a favorite among his subjects and no mutiny ever threatened to dethrone him. His obsession with building and progress left a mark on Egypt in the form of intricately developed city centers and architectural marvels.

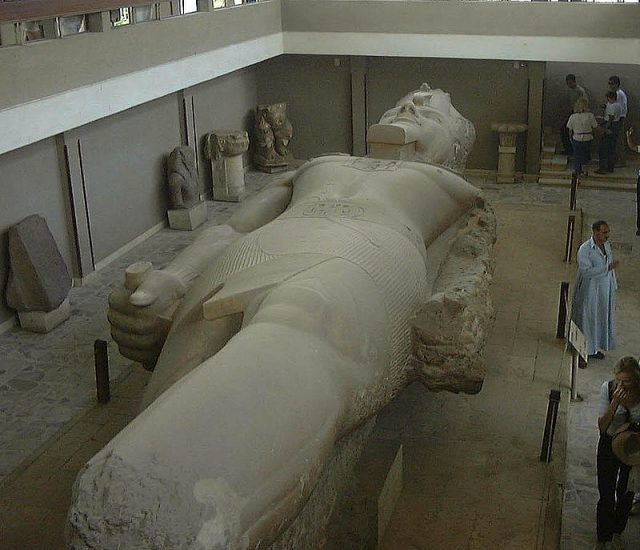

Also, some of the structures built during his reign show that he was, like most pharaohs, somewhat narcissistic: at the Great Temple of Ptah near Memphis, his minions erected a giant 91-ton statue of him.

Ramesses’ mummy was discovered in 1881 in the tomb of a high priest named Pinedjem II who lived almost 400 years after the great pharaoh’s reign. The mummy was likely moved from the pharaoh’s original tomb in the Valley of the Kings, designated KV7, after looters desecrated the burial chamber and the priests of the time feared that someone might even try to ruin or steal the body. Upon discovery, the body of Ramesses the Great was was in pristine condition. His skin was entirely preserved, as well as most of the hair on his head. Since his facial features remained virtually intact, researchers compared them to the statues which represented him. They concluded that many statues accurately depicted Ramesses and his strong jaw and aquiline nose.

Due to several factors, including the humidity of the room in which Ramesses’ mummy was kept at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the condition of the mummy began to deteriorate. By early 1970s it was infested with bacteria and started showing signs of decomposition. This prompted Egyptian authorities to search the world for expert Egyptologists and restorers who would be capable of preserving the ancient body. Such experts were found in France.

However, in order for Ramesses’ mummy to be transported to France, the long-deceased pharaoh needed to have a valid passport. At that time, French laws dictated that all persons, dead or alive, needed to have valid identification documents in order to legally enter France. Since the mummified king desperately required the help that only French experts could provide, Egyptian authorities issued a valid passport for Ramesses the Great. At the time when the document was officially issued, the legendary pharaoh had been dead for more than 3,000 years. The “occupation” section of the document stated “king (deceased).”

When the plane with Ramesses’ remains arrived in Paris, the mummy was greeted by a military procession and received full military honors. Whether dead or alive, kings who enter France on official business are entitled to such a reception. Therefore, Ramesses became the first pharaoh in history to hold an official Egyptian passport and to receive full military honors in France.

When the pharaoh’s remains were repaired, they were returned to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo where they can be visited today. Upon the mummy’s return, the remains were inspected by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and his wife, who wanted to make sure that the body of one of the icons of Egyptian history was properly refreshed. They were seemingly satisfied.