Before the invention of photography, people needed a different method of commemorating the faces of the deceased. They had paintings, of course, but another service was saved for the elites: the death mask.

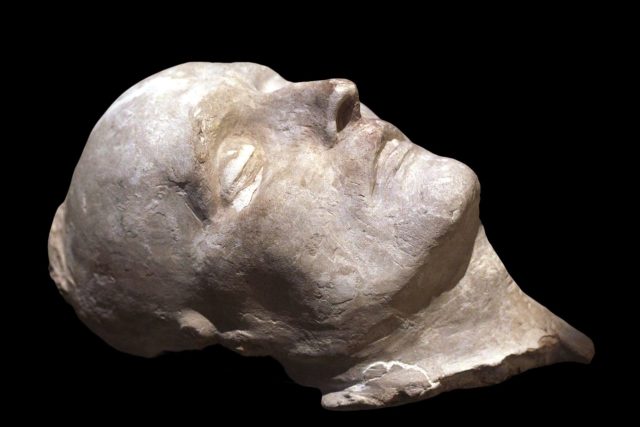

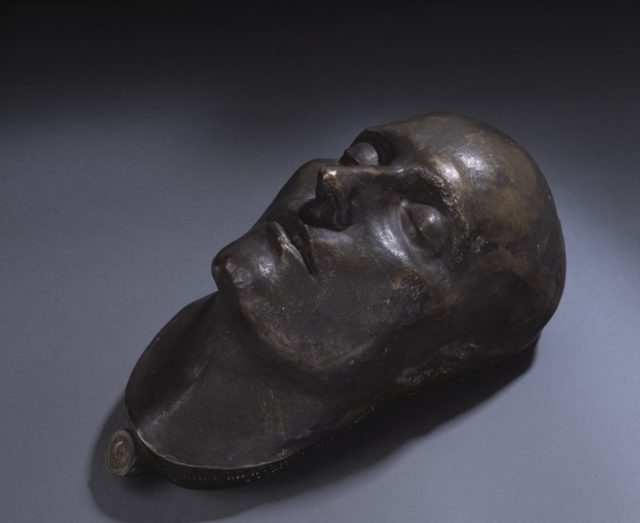

This technique was used in many nations to create a lasting memento of a ruler. Wax or plaster cast was poured onto the face of the deceased, forming a sculptural portrait. Used mainly for funeral ceremonies, the masks were later displayed at universities, museums, and libraries. Although they were most commonly made for state leaders, the honor was also granted to some lesser royalties, or to prominent scientists and artists.

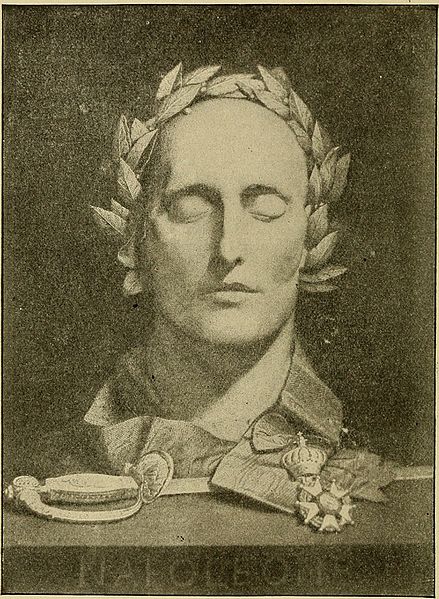

During the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte, France had a strong tradition of creating death masks. The notorious emperor who conquered much of Europe was exiled to the island of St. Helena after his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. There, surrounded by several French and British doctors, Napoleon died on May 5, 1821, at the age of 51. In keeping with the French custom, a mask was sculpted a day after his death. In fact, several death masks were created with the face of Napoleon, and mystery surrounds them even today.

Current historians aren’t sure who created Napoleon’s original death mask. The most common belief is that François Carlo Antommarchi, the emperor’s personal doctor, made the first mold, from which many bronze copies were later sculpted. Another, less popular theory is that Francis Burton, a British surgeon present at the autopsy of Napoleon, did the original cast. By that theory, Antommarchi would have made a copy from Dr. Burton’s mask, which he brought back to France to create several more copies.

Historians also don’t agree on which of the two physicians presided over Napoleon’s autopsy, although both were definitely present. The medical team found a widespread stomach cancer to be the exiled emperor’s cause of death.

A third theory about the mask is that Madame Bertrand, Napoleon’s attendant, managed to steal pieces of the mold created by Francis Burton, leaving him with only the ears and the back of the head. Some people believe that Madame Bertrand gave the mask to Antommarchi a year after she allegedly stole it. According to this theory, the attendant was later sued by Burton for custody of the mask, but the British doctor failed in his attempt.

Antommarchi sent a copy of the mask to Lord Burghersh, the British ambassador to Florence, who intended to pass it on to Antonio Canova, a famous sculptor. Canova was asked to create a statue of Napoleon based on his death mask, but the artist died before he could complete his work. The mask remained with Lord Burghersh.

Today, the piece is known as the Antommarchi-Burghersh mask and resides in the Musée de l’Armée in Paris. Another mask, which is considered to be one of the first created, is called the Bertrand mask (after Madame Bertrand) and is housed in the Musée de Malmaison in Rueil-Malmaison.

There are several other plaster casts of the face of Napoleon scattered around the world, but those two examples are likely the closest to the original.

Yet another controversy over the death mask of Napoleon Bonaparte revolves around the appearance of the casts. The emperor is presented as youthful and healthy, but given his illness, historians believe he would have looked much older.

The once great-ruler lived in terrible conditions and spent his last days working on his memoirs. After his death, Napoleon was buried on St. Helena. Twenty years later, his body was exhumed and transferred to Paris, where he was given a magnificent state funeral. The memorial in 1840 was attended by thousands of spectators, all wishing to say their last goodbyes to the great conqueror.