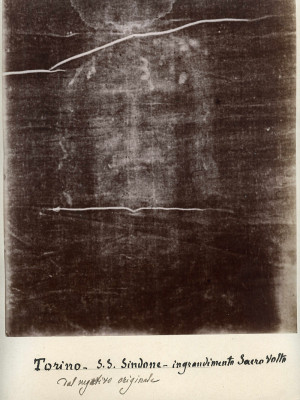

Some venerate it as the burial cloth of Christ. To others, the Turin Shroud is nothing more than a medieval hoax. Now, science has come down on the side of the believers. Researchers have dated a sample of the 14ft linen sheet to anything between 300BC to 400AD.

They used forensic tests to compare fibres from the shroud with a range of ancient fabric samples. And they discovered that the material could have been made in Jesus’s lifetime. Their results contradict a landmark 1988 study, spearheaded by the British Museum, which used carbon dating to examine the cloth.

It said the shroud, which has an imprint of a bearded man with wounds consistent to being nailed to a cross, was actually made in the Middle Ages – more than 1,000 years after the Crucifixion. But scientists at Padua University believe the original results could have been skewed by centuries of water and fire damage.

Key to the findings are three new tests, two chemical ones and one mechanical, the first two were carried out using infra-red light, and the other using Raman spectroscopy – which measures radiation through wavelengths and is commonly used in forensic science.

The results dated the fibres from the cloth to a period between 300BC to 400AD, which covers the years of Christ’s life. Debate has raged whether the image is that of Christ or a fake from the Middle Ages. But what is certain is that experts have never really been able to explain how the image was made.

Carbon 14 tests were conducted on the cloth in 1988 and these findings suggested it dated from between 1260 and 1390. However, some scientists have since claimed that contamination over the ages from water damage and fire, were not taken sufficiently into account and could have distorted the results.

Since then, there have been several requests for fresh tests but Church chiefs have always refused – and this is why Professor Fanti and his team had to rely on fibres that were used in the 1988 tests. Before he retired last month pope Emeritus Benedict XVI gave permission for the Shroud to go on display as a ‘last gift’ to the millions of Catholics before he retired from public office.

Thirteen years ago when he was plain cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Benedict wrote that the shroud was a ‘truly mysterious image, which no human artistry was capable of producing. In some inexplicable it appeared imprinted upon cloth…’

The linen cloth, believed by some to have wrapped the body of Jesus Christ, has captivated the imagination of historians, church chiefs, sceptics and Catholics for more than 500 years.

There are no definite historical records concerning the shroud prior to the 14th century. Although there are numerous reports of Jesus’ burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the 14th century.

But there is no historical evidence that these refer to the shroud currently at Turin Cathedral. A burial cloth, which some historians maintain was the Shroud, was owned by the Byzantine emperors but disappeared during the Sack of Constantinople in 1204. Historical records seem to indicate that a shroud bearing an image of a crucified man existed in the small town of Lirey around the years 1353 to 1357. It was in the possession of a French Knight, Geoffroi de Charny, who died at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356.

However the correspondence of this shroud with the shroud in Turin, and its very origin has been debated by scholars and lay authors, with claims of forgery attributed to artists born a century apart. Some contend that the Lirey shroud was the work of a confessed forger and murderer.

The history of the shroud from the 15th century is well recorded. In 1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in a chapel of Chambéry, capital of the Savoy region, where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches.

In 1578 Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy ordered the cloth to be brought from Chambéry to Turin and it has remained at Turin ever since. The shroud has had many notorious admirers. It even obsessed Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, who wanted to steal it so he could use it in a black magic ceremony. In May 2010, five years after he became Pope, Benedict authorised a public viewing of the Shroud – the first since 2000 and also 15 years ahead of its next scheduled public display.

Want The Vintage News delivered straight to your inbox? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter!