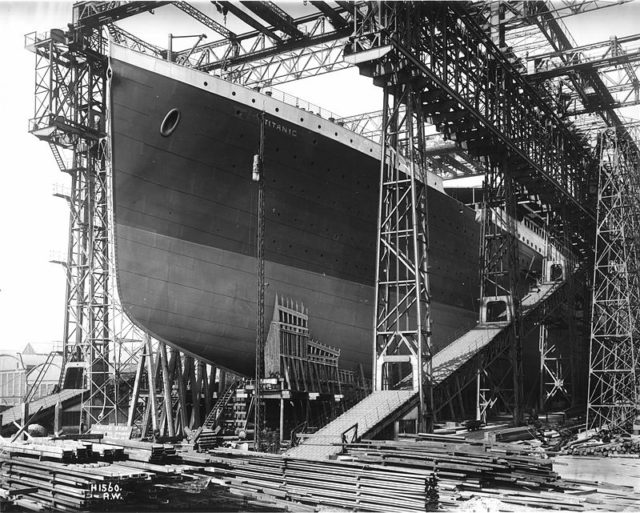

The sinking of the RMS Titanic is one of the most well-known maritime disasters in history. Owned by the White Star Line, the ship was ordered from Harland and Wolff builders in Ireland in 1908. Work began on March 31, 1909, and was completed April 2, 1912, at a cost of $7.5 million.

The ship’s designers were former naval architects: Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff’s design department; First Viscount Lord William James Pirri, chairman of Harland and Wolff from 1895 to 1924 and uncle of Thomas Andrews; Edward Wilding, Andrews’ deputy; and Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard’s chief draughtsman and general manager who was also the brother-in-law of Lord Pirrie. Significantly, Carlisle left the company after an argument with Lord Pirrie regarding the number of lifeboats Harland and Wolff ordered for the ship.

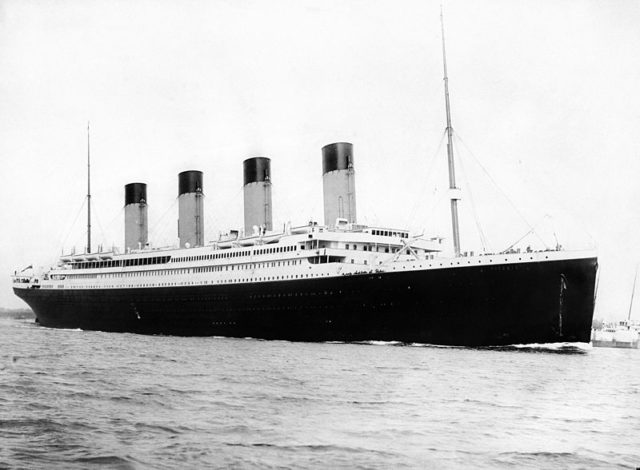

The Titanic was one of three Olympic class liners built by the White Star Line to compete with the Cunard line of ships, the Mauretania and the Lusitania. The Olympic and the Britannic were almost identical to the Titanic except for a few modifications made by Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line. Both the Titanic and the Britannic had a steel screen with sliding windows, installed along the forward half of the A Deck promenade to enable first-class passengers to view the sea under shelter.

The captain was Edward Smith, who had had a long and successful career with the White Star Line and had planned on retiring at the end of Titanic’s first voyage.

Titanic was the largest liner afloat at the time, and not only provided passenger service to New York but was a Royal Mail Ship under contract with Royal Mail and the United States Post Office.

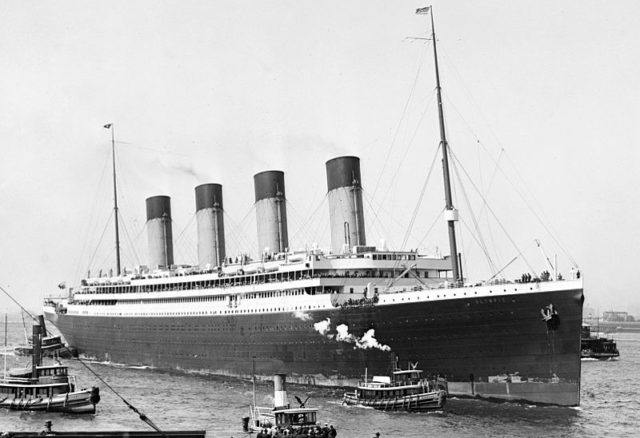

The ship’s maiden voyage began on April 10, 1912, from Southampton, England, with stops in France and Ireland, where it picked up more passengers. There were approximately 1,317 people on board–324 in First Class, 284 in Second Class, and 709 in Third Class. The ship was supposed to arrive in New York on April 17. A fire in the coal bunkers had started several days before it saile—a common occurrence in coal-powered steamships—and was extinguished on April 14 with fire hoses and by rearranging the coal.

Titanic had been called “unsinkable” by the White Star Line, and Captain Smith declared in 1907 that he “could not imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.” Therefore, little attention was paid to the iceberg warnings from off the coast of Newfoundland. The ship continued to sail at maximum speed, depending on the lookouts and the officers on the bridge to spot ice. Unfortunately, the lookouts were not supplied with binoculars.

At about 11:40 pm, lookout Fredrick Fleet spotted an iceberg directly ahead of the Titanic, but with a calm sea at night it took too long to identify, and the ship could not stop in time. The First Officer ordered the ship to turn, but such a large ship has a long reaction time; the turn took too long, and the ship’s starboard side scraped along the underwater portion of the iceberg, which punched holes in the hull below the water line. The watertight compartments failed because they were not tall enough and acted like an ice cube tray, gradually filling one after another as the ship started to list.

After two hours, the front deck of the ship was underwater, and the stern had started to rise out of the water. Titanic broke in two, and the bow slipped under the surface. The stern bobbed in the water for a few minutes, then submerged, taking hundreds of people with it.

Most survivors claimed the ship had gone down in one piece, which was the prevailing belief even though survivor Eva Hart insisted she had seen the ship break up before it sank. In a 1993 interview, she stated that although her mother tried to cover her eyes in the lifeboat, “I saw that ship sink. I never closed my eyes. I didn’t sleep at all. I saw it, I heard it, and nobody could possibly forget it. I can remember the colors, the sounds, everything,” she said. “The worst thing I can remember are the screams.” On the silence that followed, she remarked, “It seemed as if once everybody had gone, drowned, finished, the whole world was standing still. There was nothing, just this deathly, terrible silence in the dark night with the stars overhead.”

The nearest ship to respond was the Carpathia, which steamed at full power despite the icebergs, hoping to save passengers’ lives. Still, it took until 4 AM for the ship to arrive and most of the people who survived the sinking had frozen in the icy water. In all, only 710 people survived, mostly first-class passengers. The low survival rate is blamed on the lack of enough lifeboats and the crew’s fear, due to never having participated in a drill of filling them to capacity. Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews died in the disaster, but even though only women and children were being loaded into the lifeboats, Bruce Ismay got into one and survived.

The Carpathia picked up only survivors in lifeboats, and the CS Mackay-Bennett was sent to retrieve bodies. After seeing how many bodies there were, the captain and the embalmer decided to identify only first-class passengers. Some bodies were unidentifiable and were buried at sea, while others were taken to nearby cemeteries in Nova Scotia and buried. Occasionally, bodies were found floating hundreds of miles from the site, with the last being picked up in June. Of all of the missing passengers and crew, only 333 were recovered and either turned over to relatives or given a proper burial without being claimed.

Robert Ballard, a member of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Institution, found the Titanic wreckage in 1985 after years of searching. He confirmed Miss Hart’s statement that the ship had broken in two as the stern and the bow sections lay almost a third of a mile apart in the deep ocean off the coast of Newfoundland.

One reason given for the collision with the iceberg included an unsafe speed due to the persistence of Bruce Ismay, who allegedly directed Captain Smith to increase speed in order to set a record for the trip. However, other sources say that full speed was normal for transatlantic passenger ships.

Journalist Senan Molony has proposed that the Titanic sunk not directly because of the iceberg but as a result of the fire in the coal bunker. According to Independent, Molony claims the fire was burning unnoticed for three weeks before the ship went down and it was due to the “out of control” fire that the ship’s bulkheads were weakened enough to allow the iceberg to pierce the outer hull. Many experts have debunked Molony’s theory and supposed evidence.

Titanic’s sister ship, the RMS Olympic, started her maiden voyage on June 14, 1911, on the same route Titanic would later take, and arrived in New York on June 21, 1911. She completed four journeys before an incident with British cruiser HMS Hawke on September 20, 1911, caused the two ships to collide. The Olympic had two large holes in her starboard side — causing two watertight compartments to flood — along with damage to the propeller shaft. The ship was able to return safely to Southampton under her own power. The Royal Navy inquiry blamed the incident on the Olympic, which cost the White Star Line thousands of dollars in repairs, subsequent loss of revenue, and legal fees.

Author Robin Gardiner has provided one of the most controversial conspiracy theories regarding the two ships. In Titanic: The Ship That Never Sank, Gardiner states his opinion that the ship that sank that April morning was not the Titanic at all, but the Olympic disguised as the Titanic.

Because of the Inquiry’s conclusions in the Olympic incident, the White Star Line’s insurance agent, Lloyd’s of London, purportedly refused to pay the claim, causing a delay in repairs to the Olympic and delaying the maiden voyage of the Titanic. Gardiner claims the White Star Line disguised the Olympic as the Titanic to recover financial losses. They did this by swapping out parts of the ship that had the Titanic’s name attached. The seacocks were opened so the ship would take on water very slowly while the crew and passengers were transferred to other ships waiting nearby.

One factor in Gardiner’s reasoning is based on the fact that the Olympic‘s trials lasted two days while the Titanic‘s took only 12 hours. He asserts that full speed testing of the disguised ship was never done because the repaired hull from the collision with the Hawke could not survive high speeds.

Gardiner believes that an iceberg was not capable of the damage that sank the Titanic and that the ship hit one of the rescue ships in the darkness. He also claims the Titanic continued service for the White Star Line for 25 more years as the Olympic.

Many reviewers have criticized the book. Most reputable Titanic websites explain why Gardiner’s theories fail.

Countless movies and books from reputable and non-reputable sources have been offered to the public, notably James Cameron’s 1997 film, Titanic. Cameron went to great lengths to assure his movie would be historically correct, right down to the china used. Other than the characters of Jack and Rose and their immediate circle, the movie was probably the most faithful depiction of the fateful journey.