The date was January 24, 1848 and a carpenter, James Marshall, was constructing Sutter’s Mill, a sawmill, when he found gold in a river bed in the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Sacramento. This find led to the historic gold rush that hit California from 1848-1855. During that time an estimated 300,000 people, colloquially known as the “Forty-niners” (for the year 1849), journeyed to California from all over the world. In just seven years San Francisco developed from a struggling village of two hundred residents to a major town with over thirty five thousand people living and working to support the gold fields.

The miners used their gold to pay for food and lodging as well as the ubiquitous whiskey and women! In turn, the shop or saloon owners would buy goods from the purveyors that transported supplies from San Francisco to the goldfields, and eventually the gold would find its way to local banks and gold dealers. Prior to 1854 the banks and dealers would then turn to private mints to melt the gold into gold pieces and bars, but in 1854 the San Francisco Mint was opened and the gold was minted into official U.S. gold coins. The majority of the gold was then transported to New York. It was sent by sea from San Francisco down the west coast of the continent to Panama City. There it was transported across land to Aspinwall (named after William Aspinwall, who built the Panama Railroad from Panama City to Aspinwall on the Atlantic coast), and then by sea to New York.

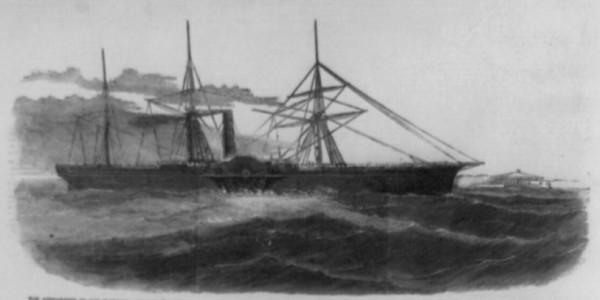

The United States Mail Steamship Company was regularly transporting mail, passengers and general cargo between New York and Aspinwall. In 1852 they launched their latest vessel to run this route, the SS Central America, a 280-foot side-paddle steam ship. In the five years, and almost ninety voyages, that she undertook between Aspinwall and New York, it is estimated that this paddle-wheeler carried one third of all the gold produced in the California fields.

Inevitably, in economic terms, any boom is followed by a bust. With the boom in California’s gold fields there was a fantastic upsurge in economic activity to support the mines. Banks in New York were tempted to invest heavily in any industry that supported this boom. The problem came when the easy pickings on the gold fields started to run out, and only professional mining concerns could then take advantage of the seams of gold that were underground. The nuggets and alluvial gold that had fuelled the initial rush were long gone, so land prices around San Francisco started to fall. Fewer people migrated to the West Coast, food and mining equipment sales collapsed, and in New York industries began to fail and investments collapsed.

In September of 1857, a major bank in New York, The Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, collapsed amid rumors of fraud and theft. This led to panic among the citizens of New York and initiated a run on the banks. After receiving an urgent message, the San Francisco Mint dispatched an extremely large shipment of gold, 30,000 pounds, to shore up the banks of New York.

This precious cargo was loaded, along with 476 passengers, onto the SS Central America on September 3, 1857. On the 10th of September she ran into a hurricane off the coast of North Carolina; a leak in one of the seals between the paddle wheel and the side of the ship extinguished the fire under the boiler. With the boiler out there was no steam to run the ship and no pumps to drain the bilges. She was soon in difficulty and was being tossed around like a cork in the ferocious storm. Eventually, the Marine, a two-masted brig transporting molasses from Cuba, came across the foundering SS Central America and rescued 148 women and children. The SS Central America then sank approximately 160 miles east of Cape Hatteras off the coast of North Carolina with the loss of 426 souls; the worst maritime tragedy at that time.

She lay on the seabed for 140 years until treasure hunter Tommy Thompson, of the Columbus America Group, located her lying in 8,000 feet of water. Thompson researched everything he could find regarding the sinking of the vessel and he then used sonar to scour the sea bed, covering an area of 1,400 square miles, looking for the SS Central America. Eventually he saw on the sonar printout what looked like the mast and the remains of a paddle-wheel lying in a debris field. Using this sonar printout as evidence, Thompson and his Group were awarded a license by the Admiralty to recover a vessel lying in international waters.

They sent down a remotely operated vehicle, nicknamed Nero, to find and recover the ship’s bell. With this absolute proof that the Columbus America Group had found the SS Central America, a federal judge granted the team 92% of any salvaged treasure. This opened a veritable floodgate of litigation with insurance companies, rival salvage companies, and even Capuchin Monks – all bringing forward legal claims to the gold on the sea bed.

Thompson and his group recovered three tons of gold valued at around $40 million, but salvage was suspended when the insurance companies won an appeal and the courts reversed their decision to award Thompson the salvage rights. The litigation dragged on until eventually, in 1993, the rights were again awarded to Thompson and Columbus America Group in exchange for a payment to the insurance companies.

The Columbus America Group was made up of 160 backers from Thompson’s hometown of Columbus, Ohio, who raised $12.7 million. They had faith in Thompson and agreed to support him, believing that the SS Central America would make them rich. But sadly, they never received a penny from the fabled wealth of gold. Thompson claimed that the money from the coins he sold was used for legal fees to fight the plethora of cases that were raised against them. He sold the gold bars for an estimated $50 million and fled when his investors slapped a law suit on him. A warrant of arrest was issued, but by the time the marshals arrived at this mansion in Florida he had fled.

Thompson had been arrested in January 2012 at a hotel near Boca Raton in Florida – he failed to appear before a federal judge and a charge of contempt of court was levied against him. In April he was brought to court to answer that charge, and as part of a plea agreement on this contempt of court charge he was required to answer questions, on behalf of the Columbus America investors, concerning the location of a hoard of gold coins. The first of the hearings was held on October 19th, with federal prosecutors saying that his answers were evasive, so a new hearing was set down for October 26th. Two days before this hearing Thompsons’s lawyer cancelled the hearing saying he had advised Thompson not to say anything more on the grounds that it may incriminate him. His investors accused Thompson of chicanery, saying his story was simply too far-fetched to have any grain of truth in it. Thompson inferred that he had no idea where the coins were, who he had given them to, or how he was to get them, or the proceeds from the sale, back.

As Thompson had not completed the salvage of the SS Central America, and with Thompson missing, the courts eventually appointed a new salver to undertake the salvage. They appointed Odyssey Marine Exploration to complete the job. This time all claims were carefully determined before the work commenced, with percentages of the proceeds for the insurance companies, Columbus American Group, and Odyssey agreed upon before the salvage ship left the dock. The contract was finalized in March of 2014 and to date Odyssey had recovered 3,000 gold coins and 45 bars of gold. Hopefully, this means that the small investors from Columbus, Ohio may yet realize their dream of gaining some reward from California’s fabled gold rush.