Nearly 14 years ago an archeologist and diver, Jim Delgado, found something magnificent. He was on a ship passing the San Telmo Island in Pearl Archipelago, Panama when it occurred to him that the area was known for a sunken Japanese WWII submarine. Intrigued by the story and the history behind the possible wreck, Delgado wondered about initiating a mission to find it. Luckily, from his ship he saw something towering on the island. It was all rusted out and Delgado felt he had to go investigate.

Delgado managed to find a beached submarine in the area mentioned in the stories he had heard. However, what he did not anticipate was that the submarine was not Japanese, as the stories relate. Nor was it a submarine from WWII – it was much older. Delgado, more intrigued than ever, knew he wanted to investigate the mysterious submarine.

Finding out the name of the submarine took almost two years. A colleague helped Delgado find an old blueprint in a 1902 magazine that had been signed by Julius H. Kroehl, 1864. The magazine stated that there was a wreck around the San Telmo Island and described almost exactly what Delgado found.

Then Delgado found a New York Times article dated 1866 that outlined an event that happened on a New York river. According to the article, Julius Kroehl, who was a German-American who invented one of the first submarines that could be fully submerged and travel under water, had been testing out his ship in the river when it sunk. If this story is true, the sunken submarine is Kroehl’s Sub Marine Explorer.

But if the sunken submarine was Kroehl’s, then why would it be in Panama if it was only tested in a New York river? After more research, Delgado found out that the first trial was actually successful; that the submarine was then taken to Panama to be used for collecting pearls. It is said that the submarine actually lasted a few weeks while collecting pearls, however, something must have gone terribly wrong to leave it rusted out in the middle of an ocean.

The submarine managed to harvest pearls successfully for a while. In 1869 another New York Times article stated that one of the pearl-harvesting missions brought up almost 10 tons of oysters and pearls which estimated about $2,000. However, all men who had been on the submarine contacted fever and decompression sickness; the vessel was condemned as harmful to the crewmembers’ health. A year after the submarine arrived in Panama, Kroehl himself died from decompression sickness from diving in the submarine. The sub was then taken to the island where it has remained beached ever since. Delgado found it nearly 130 years later.

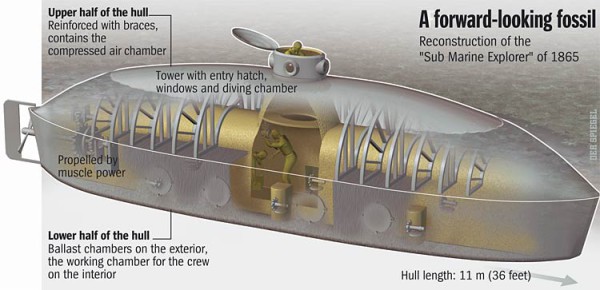

Sub Marine Explorer is a submersible built between 1863 and 1866 by Julius H. Kroehl and Ariel Patterson in Brooklyn, New York for the Pacific Pearl Company. It was hand powered and had an interconnected system of a high-pressure air chamber or compartment, a pressurized working chamber for the crew, and water ballast tanks. Problems with decompression sickness and overfishing of the pearl beds led to the abandonment of Sub Marine Explorer in Panama in 1869 despite publicized plans to shift the craft to the pearl beds of Baja California.

Sub Marine Explorer had an external high air pressure chamber which was filled with compressed air at a pressure of up to 200 pounds per square inch (1,400 kPa) by a steam pump mounted on an external support vessel. Water ballast tanks were flooded to make the vessel submerge. Pressurized air was then released into the vessel to build up enough pressure so it would be possible to open two hatches on the underside, while keeping water out. This meant that air pressure inside the submarine had to equal water pressure at diving depth, exposing the crew to high pressure, making them susceptible to decompression sickness, which was unknown at the time. To surface, more of the pressurized air was used to empty the ballast tanks of water.

A contemporary (August 1869) newspaper account of dives in Sub Marine Explorer off Panama documents 11 days of diving to 103 feet (31 m), spending four hours per dive, and ascending with a quick release of the pressure to ambient (sea level) pressure. Modern reconstruction of Explorer’s systems suggests an ascension rate of 1 foot per second (0.30 m/s), or a rise to the surface in just under two minutes. The problems of decompression do not appear to have been clearly understood; the contemporary reference notes that at the conclusion of the dives, “all the men were again down with fever; and, it being impossible to continue working with the same men for some time, it was decided, the experiment having proved a complete success, to lay the machine up in an adjacent cove….”(The New York Times, August 29, 1869)

source"

title="The submarine's rusting hull was well-known to locals, but they had presumed it to be a remnant of World War II.

source"

title="The submarine's rusting hull was well-known to locals, but they had presumed it to be a remnant of World War II.