Hilts (Steve McQueen) strings a wire across the road to obtain a motorcycle. McQueen himself played the German motorcyclist who hits the wire.

Charles Bronson, who portrays the chief tunneler, brought his own expertise and experiences to the set: he had been a coal miner before turning to acting and gave director John Sturges advice on how to move the earth. As a result of his work in the coal mines, Bronson suffered from claustrophobia just as his character had.

One day, the police in the German town where the film was shot set up a speed trap near the set. Several members of the cast and crew were caught, including Steve McQueen. The Chief of Police told McQueen “Herr McQueen, we have caught several of your comrades today, but you have won the prize [for the highest speeding].” McQueen was arrested and briefly jailed.

Several cast members were actual P.O.W.s during World War II. Donald Pleasence was held in a German camp, Hannes Messemer in a Russian camp and Til Kiwe and Hans Reiser were prisoners of the Americans.

During the climactic motorcycle chase, John Sturges allowed Steve McQueen to ride (in disguise) as one of the pursuing German soldiers, so that in the final sequence, through the magic of editing, he’s actually chasing himself.

During production, Charles Bronson met and fell in love with David McCallum’s wife, Jill Ireland, and he jokingly told McCallum he was going to steal her away from him. In 1967, Ireland and McCallum divorced, and she married Bronson.

Steve McQueen also personally attempted the jump across the border fence, but crashed. The jump was successfully performed by Bud Ekins.

Donald Pleasence had actually been a Royal Air Force pilot in World War II, who was shot down, became a prisoner of war and was tortured by the Germans. When he kindly offered advice to the film’s director John Sturges, he was politely asked to keep his “opinions” to himself. Later, when another star from the film informed John Sturges that Pleasence had actually been a RAF Officer in a World War II German POW Stalag camp, Sturges requested his technical advice and input on historical accuracy from that point forward.

Wally Floody, the real-life “Tunnel King” (he was transferred to another camp just before the escape), served as a consultant to the filmmakers, almost full-time, for more than a year.

Paul Brickhill, who wrote the book from which the film is based, was piloting a Spitfire aircraft that was shot down over Tunisia in March 1943. He was taken to Stalag Luft III in Germany, where he assisted in the escape preparations.

Although Steve McQueen did his own motorcycle riding, there was one stunt he did not perform: the hair-raising 60-foot jump over a fence. This was done by McQueen’s friend Bud Ekins, who was managing a Los Angeles-area motorcycle shop when recruited for the stunt. It was the beginning of a new career for Ekins, as he later doubled for McQueen in Bullitt (1968) and did much of the motorcycle riding on the television series CHiPs (1977).

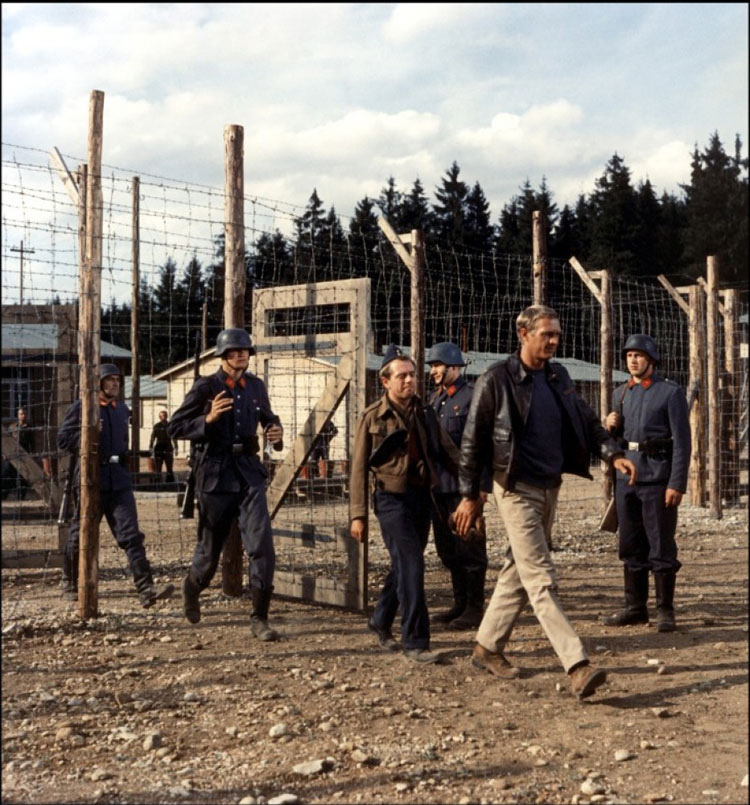

During idle periods while The Great Escape (1963) was in production, all cast and crew members – from stars Steve McQueen and James Garner to production assistants and obscure food service workers – were asked to take thin, five-inch strings of black rubber and knot them around other thin strings of black rubber of enormous length. The finished results of all this knotting were the coils and fences of barbed wire seen throughout the film.

The real-life escape preparations involved 600 men working for well over a year. The escape did have the desired effect of diverting German resources, including a doubling of the number of guards after the Gestapo took over the camp from the Luftwaffe.

The motorcycle scenes were not based on real life but were added at Steve McQueen’s suggestion.

Some aspects of the escape remained classified during production and were not revealed until well after. The inclusion of chocolate, coffee and cigarettes in Red Cross packages is well documented, as is their use to bribe Nazi guards. Other materials useful for escaping had to be kept secret and were not included in the novel or screenplay. Also not revealed until many years later was the fact that the prisoners actually built a fourth tunnel called “George.”

The film was shot entirely on location in Europe, with a complete camp resembling Stalag Luft III built near Munich, Germany. Exteriors for the escape sequences were shot in the Rhine Country and areas near the North Sea, and Steve McQueen’s motorcycle scenes were filmed in Fussen (on the Austrian border) and the Alps. All interiors were filmed at the Bavaria Studio in Munich.

Steve McQueen accepted the role of Hilts on the condition that he got to show off his motorcycle skills.

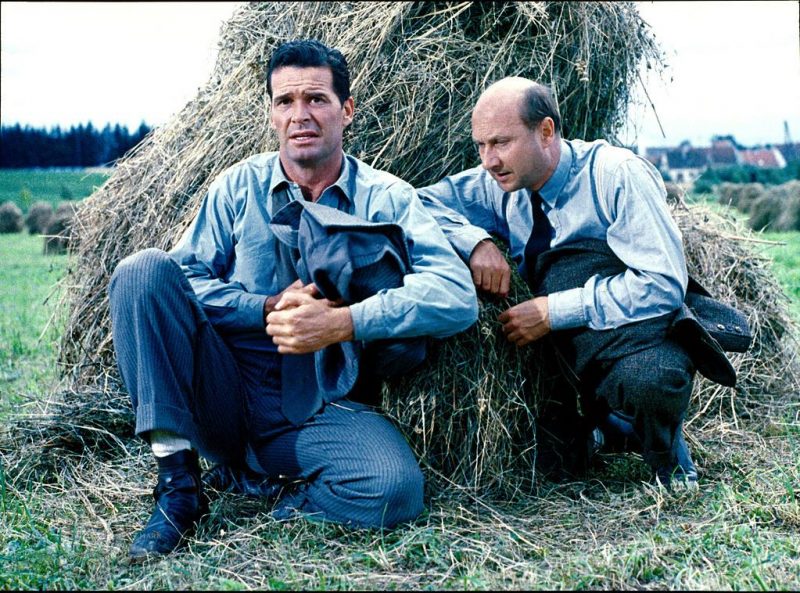

James Garner developed his “Scrounger” character from his own personal experiences in the military during the Korean War.

The nationality of a few of the prisoners in the story was changed, emphasizing American, and de-emphasizing Commonwealth and other Allied.

The motorcycle that Hilts (Steve McQueen) rides is a cosmetically modified Triumph TR6 Trophy. Bud Ekins who actually performs the famous barbed wire leap stunt, was a Triumph dealer. Triumph was McQueen’s favorite motorcycle marque. The motorcycle sidecar combination that crashes into a ditch is revealed to be a Triumph motorcycle, too. As is well known, these British motorcycle models were not in existence during the Second World War and their appearance is somewhat incongruous.

With the deaths of James Garner (Robert Hendley) on July 19, 2014 and Richard Attenborough (Roger Bartlett) on August 24, 2014, David McCallum (Eric Ashley-Pitt)and John Leyton are the last surviving stars of the film.

When celebrating the Fourth of July and pouring alcohol, Hilts (Steve McQueen) is thrown off by an ad-lib by Goff (Jud Taylor). While Hilts is drinking, Goff says, “No taxation without representation.” McQueen jumps out of character and gives him a look (and mouths, “What?”) The director must have signaled to “just go with it” and the scene continues. But it is an obvious ad-lib.

The medal that Colonel von Luger wears around his neck is the Pour le Merite, also known as the Blue Max. Originally a Prussian military honor, in the First World War it was automatically given to fighter pilots who shot down eight planes (later raised to sixteen). The Nazis replaced it with the Knight’s Cross but it could still be worn by officers who’d won it before the Third Reich.

Steve McQueen held up production because he demanded that the script be rewritten to give his character more to do.

The actual escape from Stalag Luft III occurred on March 24, 1944 – which was Steve McQueen’s 14th birthday.

There is a film company called Virgil Films. It uses the sound of Virgil Hilts bouncing his baseball inside the cooler as the introduction to its movies.

For the train sequences, a railroad engine was rented and two condemned cars were purchased and modified to house the camera equipment. Scenes were shot on the single rail line between Munich and Hamburg, and a railroad representative was on hand to advise the filmmakers when to pull aside to avoid hitting scheduled oncoming trains.

MacDonald (Intelligence) is based on George Harsh, a very good friend of Wally Floody (the real Tunnel King). They were both transferred to Belaria before the escape. Harsh was a very interesting character who was from the American south and had joined the RCAF as a tail-gunner. In the 1920s Harsh had committed murder and was sent to jail for life. A medical student, Harsh performed an appendectomy on a dying prisoner and saved his life. The governor of Georgia granted him a pardon and he was set free. After the war, he had personal problems as he was plagued by guilt over the crime he committed as a youth; on top of adjusting to life after fifteen years in captivity (12 years on the Georgia chain gang, followed by three years as POW). On Christmas Eve 1974, he did shoot himself but survived. A stroke soon after left him partially paralyzed. When that happened, Wally Floody and his wife brought him up to their Toronto home and looked after him. He eventually went to live -at his own urging- at the Veteran’s Wing at the Sunnybrook Medical Centre. He died in January of 1980.

Three of the actors, Steve McQueen, James Coburn and Charles Bronson starred together in the movie The Magnificent Seven (1960), also directed by John Sturges and scored by Elmer Bernstein.

Richard Attenborough was an RAF air gunner/photographer who served in the RAF for three years unlike his character, based on Squadron Leader Roger Bushell who was a Spitfire Pilot in 92 Squadron in the early years of World War Two.

When the Bavaria Studio’s backlot proved to be too small, the production team obtained permission from the German government to shoot in a national forest adjoining the studio. After the end of principal photography, the company restored (by reseeding) some 2,000 small pine trees that had been damaged in the course of shooting.

The song sung by Ives & McDonald on 4th July is “Wha Hae the 42nd?” Contrary to common belief it is not in Gaelic but a light Scots dialect of English. The 42nd Regiment of Foot was the Scottish regiment in the British Army known as the Black Watch.

Steve McQueen’s character Hilts was based on amalgamation of several characters, including Major Dave Jones, a flight commander during Doolittle’s Raid who made it to Europe and was shot down and captured and Colonel Jerry Sage, who was an OSS agent in the North African desert when he was captured. Col. Sage was able to don a flight jacket and pass as a flier otherwise he would have been executed as a spy. Another inspiration was probably Sqn Ldr Eric Foster who escaped no less than seven times from German prisoner-of-war camps.

Richard Attenborough was cast at short notice after the first choice pulled out.

Most of the planes in the airfield are actually American AT-6 Texan trainers painted with a German paint scheme, but the one actually flown is an authentic German plane, a Bucker Bu 181 ‘Bestmann.’

The hooch-making scene in the film, where the Americans celebrated Independence Day, is believed to be based on the British creating an alcohol distillery for Christmas Day celebrations in 1943. Captain Guy Griffiths, a Royal Marine pilot in Stalag Luft III who produced forged documents for the escape, also produced a comical illustration of the scene which survives to this day. This painting, along with many others, forms the basis for a Special Exhibition on ‘Griff’ at the Royal Marines Museum (Southsea, England) running from Easter 2010.

Jud Taylor, who played Goff, the third American in the prison, said the camp set was so authentic and impressive that one day he came upon a man walking his dog who was very distressed when he came upon the site. The man was greatly relieved, Goff said, when he learned it was just a movie set.

The gold medallion Steve McQueen wears throughout the film was a present from his wife.

The film was shot on location in a German forest. To make room for the camp set, several trees had to be bulldozed. John Sturges had to show the West German Minister of the Interior his plans and, to get permission to bulldoze, had to promise to plant two seeds for every tree felled when production was over.

The German characters were cast from actors out of Munich, including Hannes Messemer and Til Kiwe. Both had their own prisoner of war experiences. Messemer had been captured on the Eastern front by the Soviet army, escaped, and walked hundreds of miles to the German border. Frick served time in an American prison camp in Arizona. He tried to escape seventeen times.

The newspaper that Ashley-Pitt (David McCallum) reads on the train is the ‘Völkischer Beobachter’, a real newspaper produced for 25 years by the National Socialist German Workers Party. It served as a propaganda sheet for the Nazis and helped bring Adolf Hitler to power. At its height, it had a circulation of approximately 1.4 million. The headline for the issue seen in the film translates roughly to “Day after day, the Soviets have high, bloody losses.” Given that the escape in the film occurs in the summer of 1944, this too can be viewed as propaganda. The Nazis had transferred hundreds of thousands of troops to Normandy to stop the Allied advances after D-Day, allowing for the Soviet’s to launch Operation Bagration on 22 June, which pushed the Nazis back into Poland by the beginning of 13 July and sparked the Warsaw uprising. In all, the Soviet advance caused German losses of approximately 670,000 dead, missing, wounded and sick, including 160,000 captured. Although the date of the escape is unclear, given the green pastures around the Alps that the escapees encounter, one can easily surmise that the newspaper was putting a positive spin on the battles in the east.

John Leyton who played Willy, the Tunneler, was one of the most popular UK pop singers in the early ’60s. He recorded the title song with lyrics.

Although the German airfield displays mainly North American AT-6 Texan trainers, it is feasible that this was authentic. The Germans did use the AT-6 in some numbers as advanced trainers, which they had sequestrated from the French in 1940.

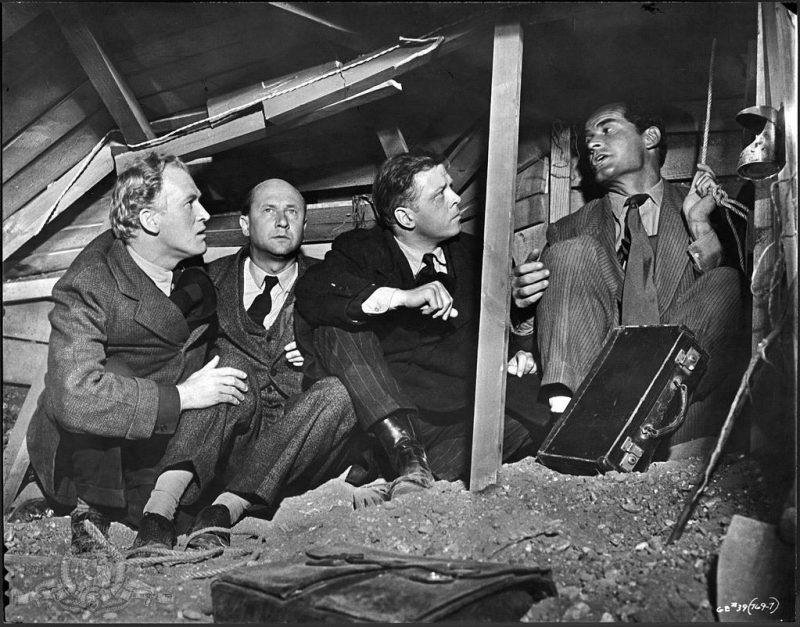

The tunnel sets were were constructed of wood and skins filled with plaster and dirt and open on one side with a dolly track running the length of the set in order to shoot scenes of prisoners scooting along through them.

Early on in the production, John Sturges began receiving memos from distributor United Artists requesting female roles in the picture. One even suggested having the dying Ashley-Pitt cradled in the lap of a beautiful girl in a low-cut blouse. The studio wanted to cast this bit by having a Miss Prison Camp contest in Munich. Sturges would have none of it.

The film features no main female characters

The character of von Luger was actually based on Friedrich von Lindeiner-Wildau. As with von Luger, the real commandant was an Oberst (Colonel), a general staff officer, and a holder of the “Blue Max” (Pour le Merite) medal. However, while the pictures on the wall of von Luger’s office are of World War I flying units, von Lindeiner-Wildau earned his Blue Max in the East Africa campaigns in 1905-07 and served as an infantry officer before and during World War I. He retired from the Army in 1919 and only joined the Luftwaffe in 1937 at ‘Hermann Goring”s personal invitation.

The motorcycle driven by the character of Virgil Hilts that is used for the fence jump is a 1962 Thunderbird Triumph, which was refurbished to look like a bike 20 years older.

In the scene following Hilts’ theft of a German motorcycle, he rolls into a nearby town, and stopped by a police officer. He tells Hilts something in German, to which Hilts kicks him away and rides off. The officer asked Hilts for identification papers Hilts doesn’t have.

On entering the workshop, Roger is heard to exclaim: “Bluey, where the hell is the air pump?” “Bluey” is an Australian slang term for someone with red hair.

The German National Railroad Bureau cooperated with the production to provide trains and logistics for the railway escape sequences. Platforms were fitted on passenger cars to accommodate huge arc lamps to illuminate the train interiors. On one flat car, a large Chapman crane was set up to swing out over the passenger car and film the jump from the moving train performed by two stuntmen disguised as Garner’s and Pleasence’s characters. The bureau attached a special radio operator to the crew to alert the train engineer to any potential traffic on the main line. The shooting schedule was squeezed in between actual runs on the rails. The bureau gave the production certain times and lengths of tracks to work on until a passenger train was scheduled to come by; the film train then had to duck onto a siding until the other passed.

In the film, several Americans (including Hilts and Henley) were among the escapees. In real life, American officers assisted with the construction of the escape tunnel, but weren’t among the escapees because the Germans moved them to a remote compound just before the escape.

After viewing the rushes, Steve McQueen decided his part was minor and undeveloped. He was particularly upset that his character virtually disappears from the film for about 30 minutes in the middle so he walked out demanding rewrites. John Sturges admitted the half-hour gap was likely a problem, but with the production already behind schedule due to the heavy rain, he felt he couldn’t take time out to do rewrites and rescheduling. James Garner said he and James Coburn got together with McQueen to determine what his specific gripes were. Garner later said it was apparent McQueen wanted to be the hero but didn’t want to be seen doing anything overtly heroic that contradicted his character’s cool detachment and sardonic demeanor. At the same time, McQueen never really liked his character’s calm acquiescence to his time in the cooler or the famous bit with the catcher’s mitt and ball. Sturges considered writing the character out of the story altogether, but United Artists informed him they considered McQueen indispensable to the picture’s success and would spring for the extra money to hire another writer, Ivan J. Moffitt, to deal with the star’s demands. McQueen returned to work.

Richard Harris was originally cast as Roger Bartlett, but dropped out because filming This Sporting Life (1963) was behind schedule and he was displeased with the diminished role of Big X after script changes had been made.

The actual camp – Stalag Luft III – was located in Zagan, Poland and the remains of the camp can be found at the following map coordinates: 51.599036, 15.310030

There are six different languages spoken or sung in the movie: English, German, French, Russian and one word in Spanish as well as two words of Latin “Lanius Nubicus” when Flight Lieutenant Blythe is describing the masked shrike or butcher bird in the forgery scene. There is also a song in a light Scots dialect where Ives and MacDonald are singing “Wha Hae the 42nd” in the 4th of July scene just before “Tom” is discovered.

John Sturges’ assistant Robert E. Relyea was an amateur pilot and offered to fly the plane himself for the sequence in which Hendley and Blythe commandeer a plane for their escape. In one segment he had to simulate the plane losing power and descending over a line of trees. According to Relyea, a farmer in his field saw the plane with its Nazi insignia coming in low over his head and threw his rake at it. Another time Relyea was arrested when he had to put the plane down in a field that happened to belong to a German aviation official. He also piloted the plane in the crash shot, knocking himself unconscious and being taken to the hospital where he woke up later feeling a sharp pain down his back.

Steve McQueen and James Garner became friends on this film. They bonded over their love of cars.