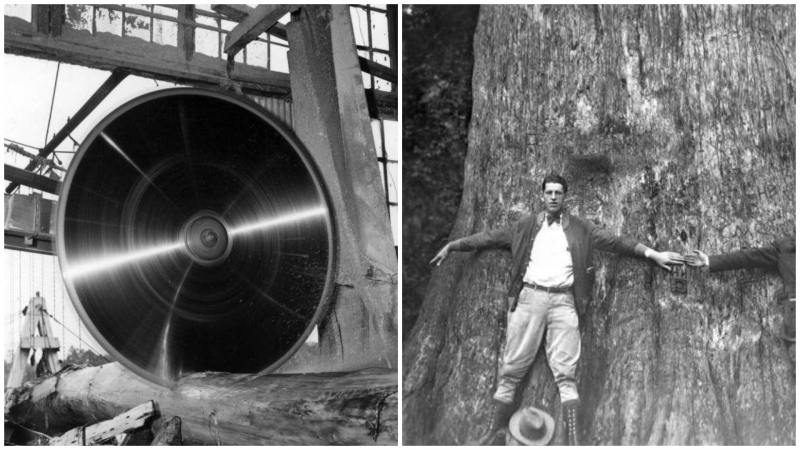

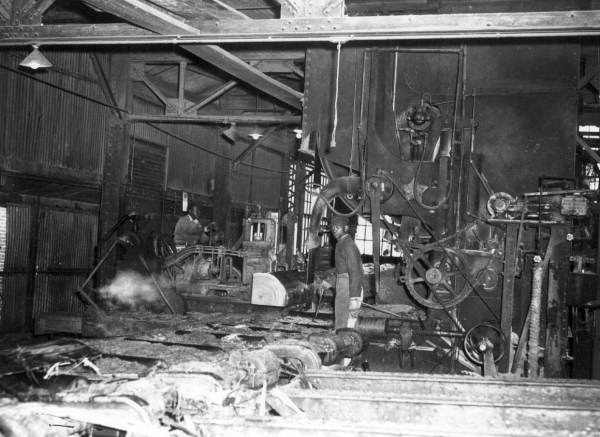

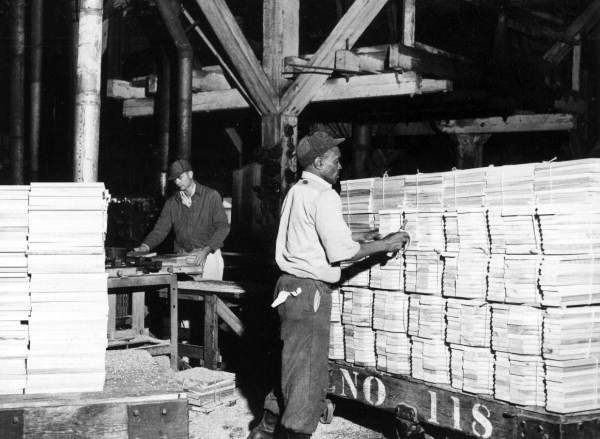

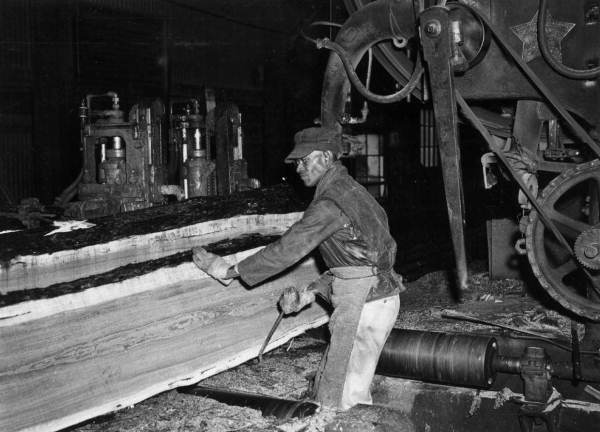

Big trees call for big sawmills with big sawblades. You have to build your sawmill to the scale of the giant trees and when you are felling the mighty trees in Florida during the 1940s – who do you turn to? Lee Tidewater Cypress Company was the world`s largest cypress logger and below is a collection of wonderful photographs from the Tidewater sawmill.

It is estimated that prior to 1845 when Florida became a state; there was still 27 million acres of virgin

timber in the state. By that date only 15 million remained. The cypress is referred to as “the Wood

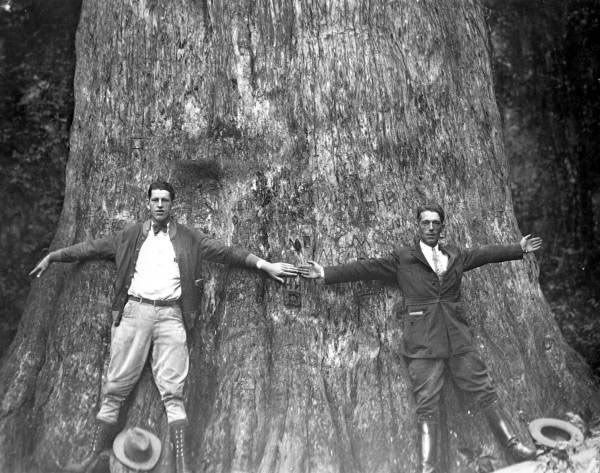

Eternal” because growing in water allows it to develop in protection from the elements. These “Giants

of the Swamp” reportedly measured up to 25 feet in circumference and reached heights up to 150

feet. Core samples revealed that some trees were more than 600 years old. The giant Bald Cypress that had sprouted at the time of the Magna Charta, and were already bearded with moss when Christopher Columbus discovered the New World, were cut down.

As the timber industry moved south to the Big Cypress in the early 1920’s, they encountered deep swamps, unstable terrain, mosquitoes, snakes, panthers and alligators, conditions that quickly discouraged logging operations in the area.

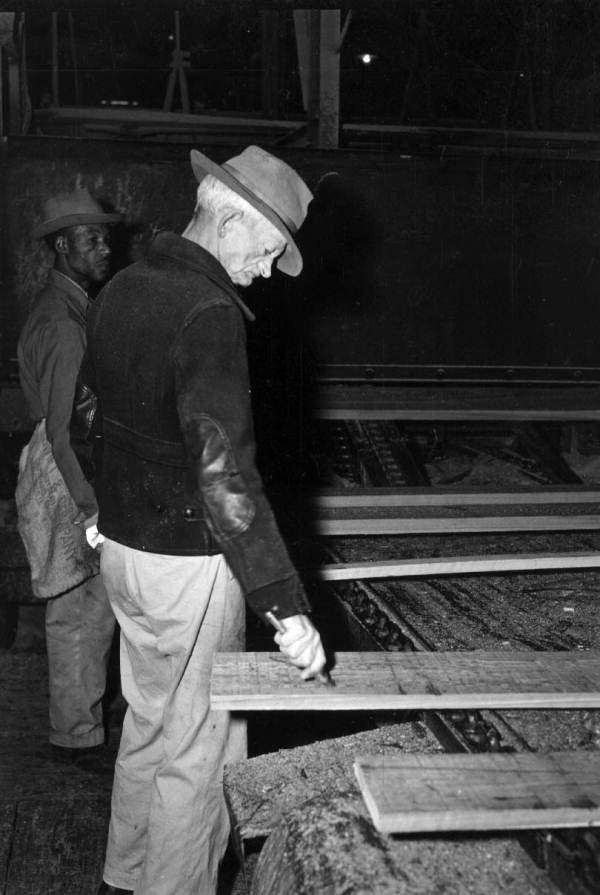

The loggers, about 200 of them, set out each Monday morning, riding the train in shacks built on flatcars. Sometimes it took three hours to reach the big trees. The men played penny-ante poker on the 40-mile trip from Copeland into the Big Cypress Swamp. This was in the early 1950s, when the Lee Tidewater Cypress Company was the world`s largest cypress logger. Although smaller operators had been logging since the turn of the century, Tidewater`s company owned two-thirds of the cypress timber in Collier County.

Its durability made the southern bald cypress one of the most desirable of all woods. The problem was that it grew in the middle of swamps, and hauling the huge trunks was difficult work. Northern logging firms could rely on rivers to move their wood to the sawmills, but Lee Tidewater had to build a railroad.

For the loggers, as much time was spent building new railroad spurs as cutting trees. The crews were made up of whites, blacks and Miccosukee Indians. They earned about $70 for a week in the swamp. Much of their time was spent standing in brackish water, potential prey to roving cottonmouth moccasins.

To fell the trees, loggers used a technique called girdling. They cut a complete circle into the trees` bark to kill them and drain them of water. Otherwise, the cypresses` weight caused the valuable trunks break into pieces when they hit the ground. A year had to pass between girdling and felling a tree.

At the height of operations, Tidewater moved more than a third of a billion board feet of cypress from Collier County to its mill in Perry, in North Florida. When the logging industry waned in the 1960s, the state began acquiring parcels of the cypress swamp.

Today Copeland is the site of a state road prison, and the logging train no longer runs. But its roadbed is still there — used by hikers exploring the 15-mile Fakahatchee Strand trail.