The history of Mexico, a country in the southern portion of North America, covers a period of more than three millennia. First populated more than 13,000 years ago, The territory had complex indigenous civilizations before being conquered by the Spanish in the 16th century. One of the important aspects of Mesoamerican civilizations was their development of a form of writing, so that Mexico’s written history stretches back hundreds of years before the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519. This era before the arrival of Europeans is called variously the prehispanic era or the pre-Columbian era.

The Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan became the Spanish capital Mexico City, which was and remains the most populous city in Mexico.

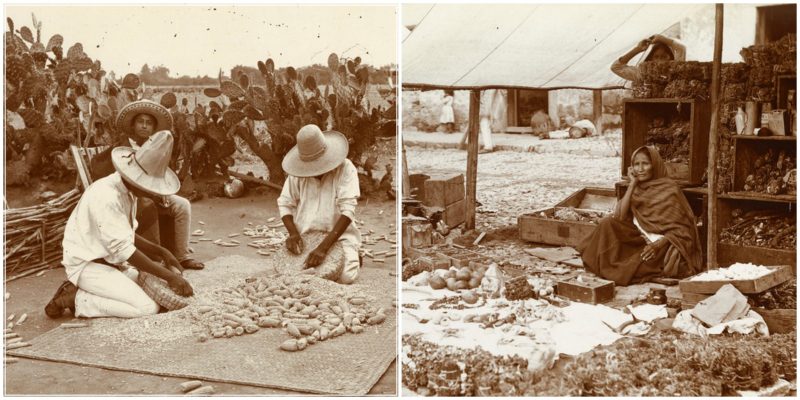

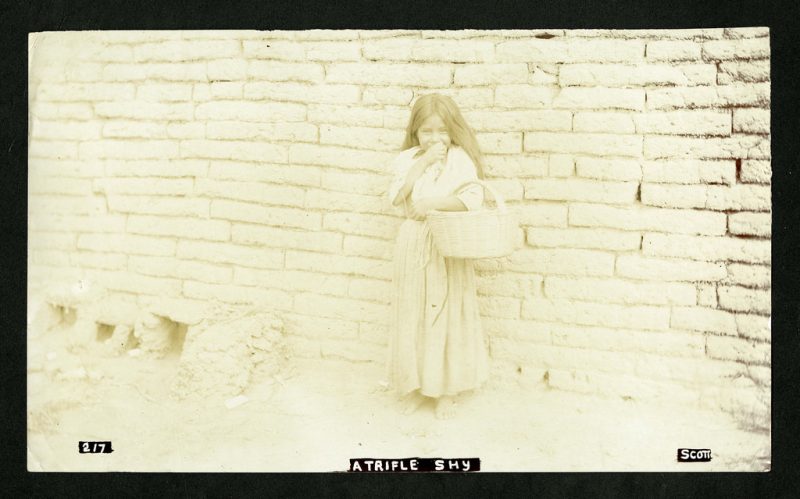

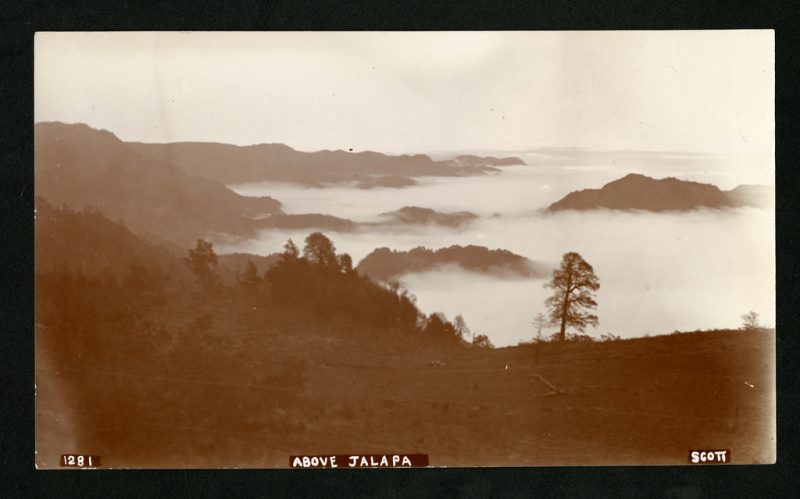

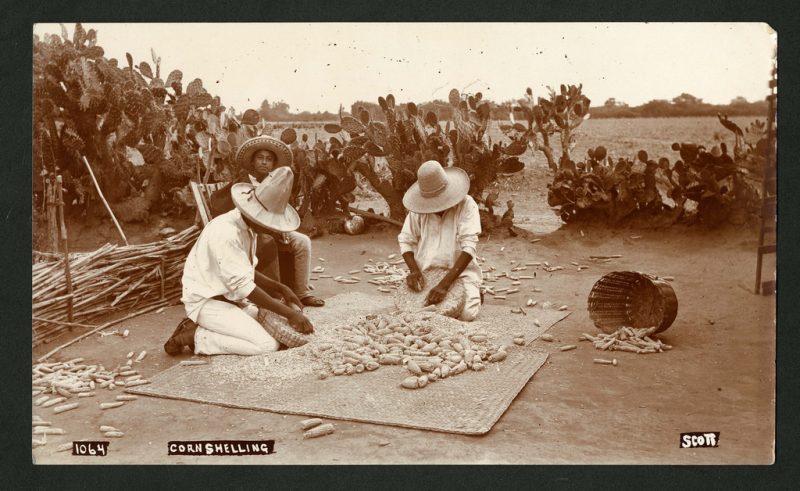

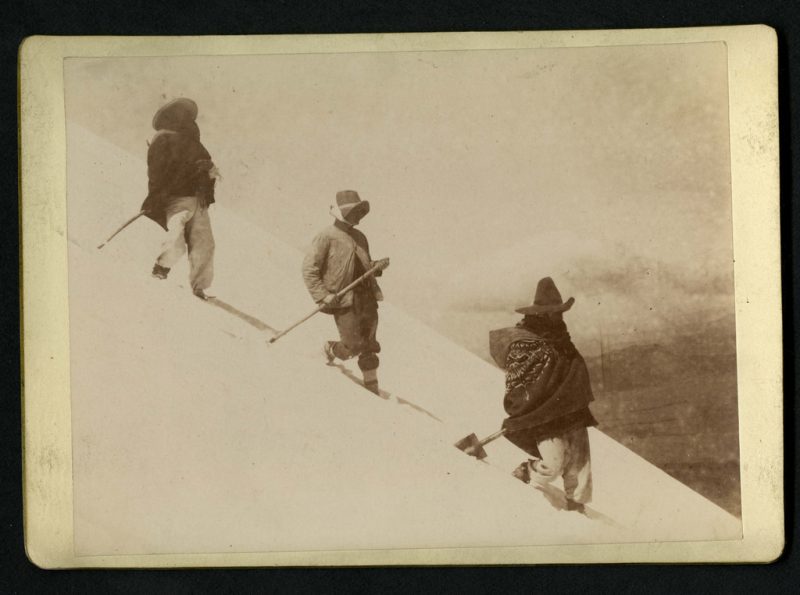

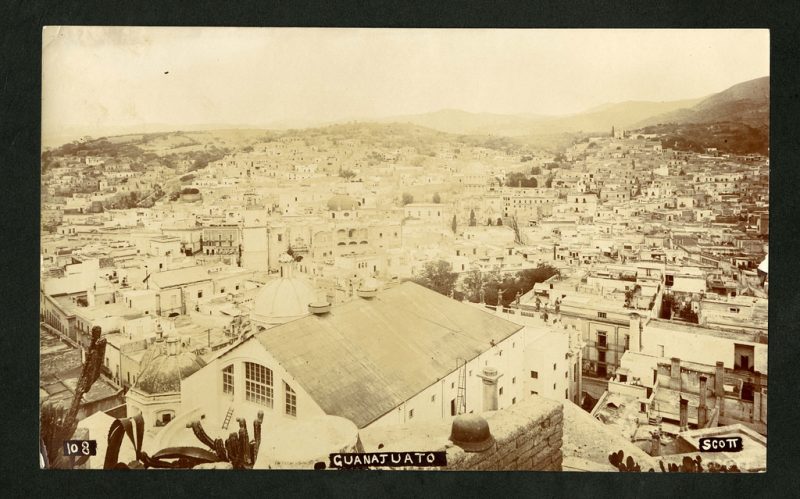

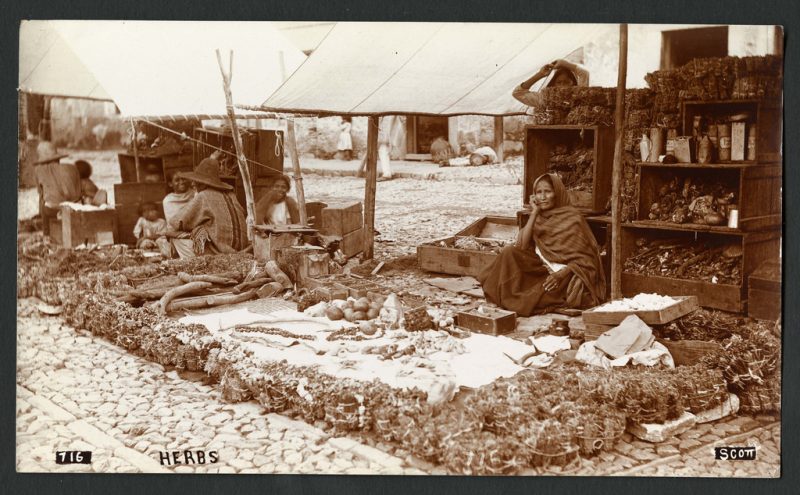

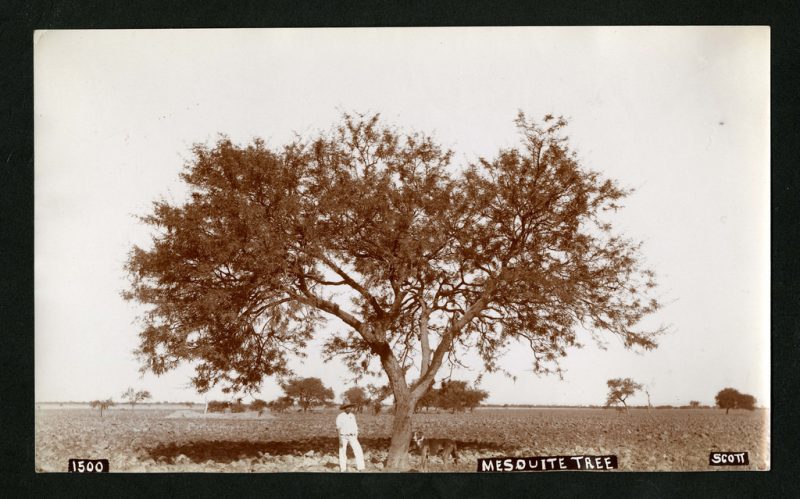

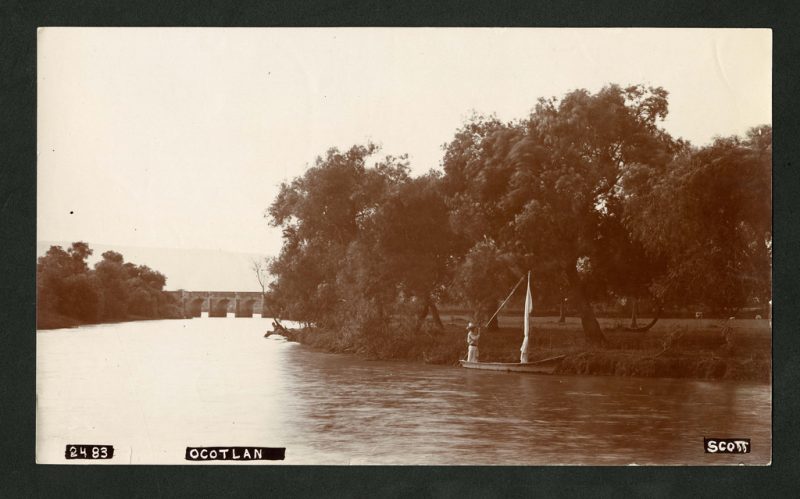

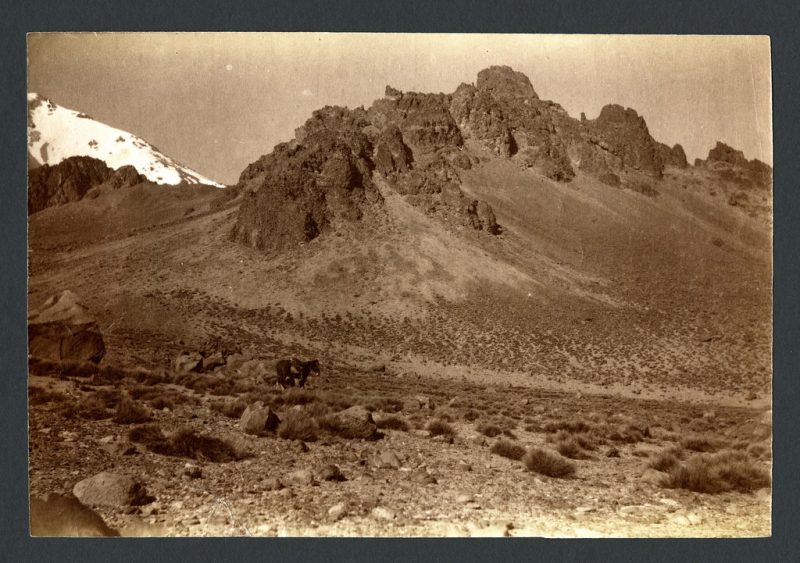

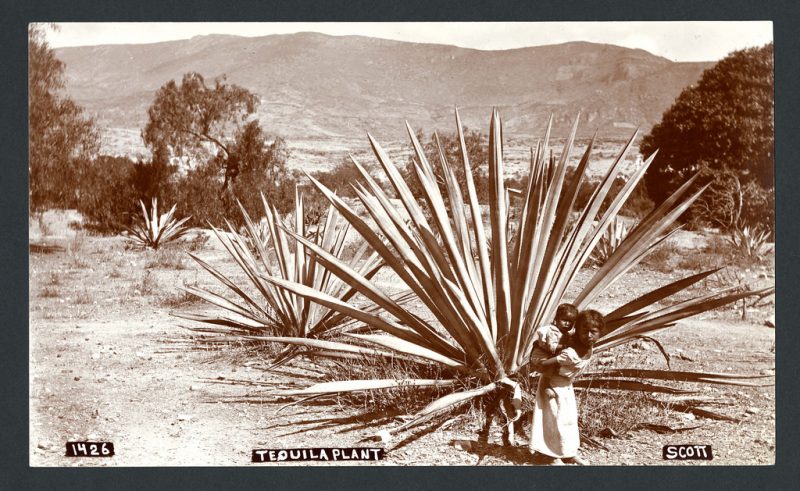

The below photos were taken by the biologists and naturalist Edward William Nelson and Edward Alphonso Goldman.

The rule of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) was dedicated to order—which meant the rule by law and the suppression of violence—and modernization of all aspects of the society and economy.Diaz was an astute military leader and liberal politician who built a national base of supporters. To avoid antagonizing Catholics he avoided enforcement of the anticlerical laws (but they remained on the books.) During this period, the country’s infrastructure was greatly improved, thanks to increased foreign investment from Britain and the U.S., and a strong, stable central government.

Increased tax revenues and better administration brought dramatic improvements in public safety, public health, railways, mining, industry, foreign trade, and national finances. He modernized the army and suppressed some banditry. After a half-century of stagnation, where per capita income was merely a tenth of the developed nations such as Britain and the U.S., the Mexican economy took off and grew at an annual rate of 2.3% (1877 to 1910), which was quite high by world standards.

Mexico moved from being a target of ridicule to international pride. As traditional ways were under challenge, urban Mexicans debated national identity, the rejection of indigenous cultures, the new passion for French culture once the French were ousted from Mexico, and the challenge of creating a modern nation by means of industrialization and scientific modernization

Tutino examines the impact of the Porfiriato in the highland basins south of Mexico City, which became the Zapatista heartland during the Revolution. Population growth, railways and concentration of land in a few families generated a commercial expansion that undercut the traditional powers of the villagers. There was anxiety and insecurity among the young men regarding the patriarchal roles they had expected to fill. The first signs came in violent crime within families and communities. However, after the defeat of Diaz in 1910 villagers expressed their rage in revolutionary assaults on local elites who had profited most from the Porfiriato. The young men were radicalized, as they fought for their traditional roles regarding land, community, and patriarchy.

Under Díaz, the population grew steadily from 11 million in 1877 to 15 million in 1910. Because of very high infant mortality (22% of new babies died) the life expectancy at birth was only 25.0 years in 1900.Few immigrants arrived. Diaz gave enormous power and prestige to the Superior Health Council, which developed a consistent and assertive strategy using up-to-date international scientific standards. It took control of disease certification; required prompt reporting of disease; and launched campaigns against tropical disease such as yellow fever.