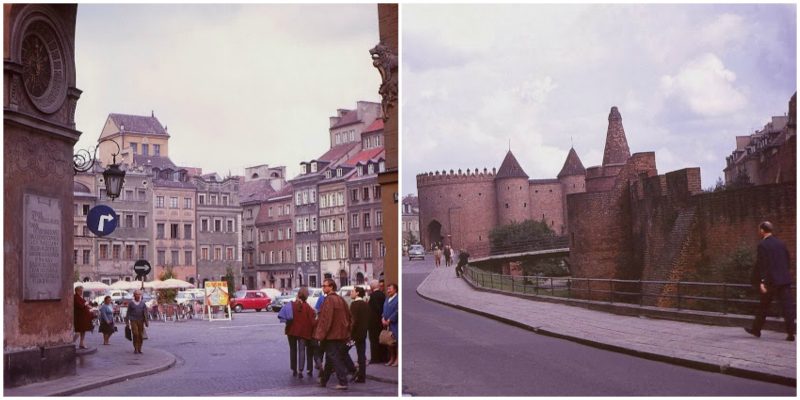

Warsaw is the sprawling capital of Poland. Its widely varied architecture echo the city’s long, tumultuous history, from Gothic churches and neoclassical palaces to Soviet-era blocks and modern skyscrapers.

The history of Warsaw spans over 1400 years. In that time, the city evolved from a cluster of villages to the capital of a major European power, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—and, under the patronage of its kings, a center of enlightenment and otherwise unknown tolerance. Fortified settlements founded in the 9th century form the core of the city, in today’s Warsaw Old Town.

The city has had a particularly tumultuous history for a European city. It experienced numerous plagues, invasions, and devastating fires. The most destructive events include the Deluge, the Great Northern War (1702, 1704, 1705), War of the Polish Succession, Warsaw Uprising (1794), Battle of Praga and the Massacre of Praga inhabitants, November Uprising, January Uprising, World War I, Siege of Warsaw (1939) and aerial bombardment—and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw Uprising (after which the German occupiers razed the city).

During the Second World War, central Poland, including Warsaw, came under the rule of the General Government, a Nazi colonial administration. Germans planned destruction of the Polish capitalbefore the start of war. On 20 June 1939 while Adolf Hitler was visiting an architectural bureau in Würzburg am Main, his attention was captured by a project of a future German town, Neue deutsche Stadt Warschau.As early as 1939 Hitler approved of a plan known as the Pabst Plan, which envisaged changing Warsaw into a provincial German city.The Germans immediately closed all higher education institutions. Since the first days, the German authorities arrested and executed Poles or took them to the concentration camps. The executions were carried out mainly in the forests around Warsaw (e.g., in Kampinos Forest or Kabaty Woods). Many small monuments on Warsaw streets today commemorate those crimes. Since the beginning of the occupation, the Nazis had organized so-called łapankas. These consisted of the sudden and accurate surrounding of a chosen place (for example, a railway station) and arresting every resident or passerby who happened to be there. in Polish “łapać” means to catch. Such actions were carried out in other occupied European countries, but not on the same scale as in Poland. Arrested people were deported either to concentration camps or forced labor camps in Germany. From 1943, a concentration camp existed also in Warsaw: KL Warschau. Until August 1944, about 200,000 Poles died in gas chambers.

The Soviet presence, symbolized by the Palace of Culture and Science, turned out to be very acute. The Stalinism lasted in Poland until 1956—like in USSR. The leader (First Secretary) of the Polish Communist party, (PZPR), Bolesław Bierut, suddenly died in Moscow during the 20th Congress of CPSU in March, probably from a hearth attack. Already in October, the new First Secretary, Władysław Gomułka, in a speech during a rally on the square in front of the PKiN supported the regime liberalization (so-called “thaw”). At first, Gomułka was very popular, because he also had been imprisoned in Stalinist prisons and as he had taken up the office of PZPR’s leader, he promised a lot, but the popularity passed pretty fast. Gomułka was gradually tightening the regime. In January 1968, he forbade to put on Dziady, a classical drama by Mickiewicz, full of anti-Russian allusions. That was “the last drop of bitterness”: then students went out on the Warsaw streets and gathered by the monument to Mickiewicz to protest against censorship. The demonstrations spread throughout all the country, the protesting people were arrested by police. This time, the students were not supported by workers, but two years later, when in December 1970 the army fired at the protesting people in Gdańsk, Gdynia and Szczecin, those two social groups cooperated—and that helped end Gomułka.