According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the word “dazzle” means “to lose clear vision especially from looking at bright light; to arouse admiration by an impressive display” and “to shine brilliantly.” Nowhere does it allude to camouflage. But that’s exactly what it meant during the first world war.

By 1917, Kaiser Wilhelm II, the Emperor of Germany, had launched an extremely successful U-boat submarine campaign. Over one fifth of British supply ships had been sunk by the Germans whose submarines were authorized to sink any vessel, even hospital ships. Hiding ships at sea was extremely difficult, as the colors of the sea and the sky are always changing.

Mirrors, tarps, and other ideas were discussed but were rejected due to feasibility and the inability to camouflage the smoke from the ship’s smokestacks. Finally, a solution called “dazzle” was proposed by renowned artist and Britain’s Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Head of Staff, Norman Wilkinson.

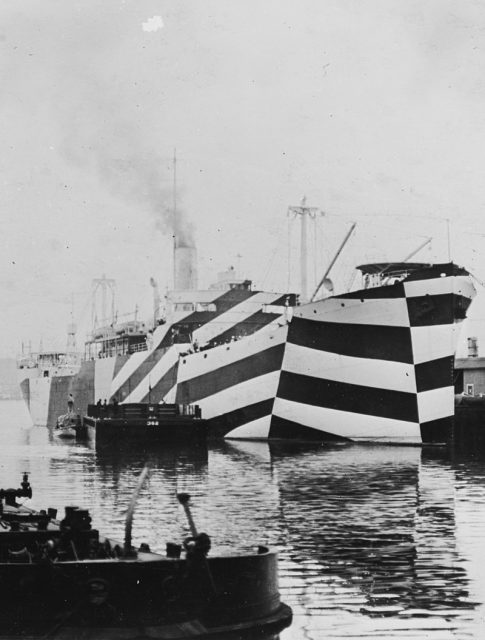

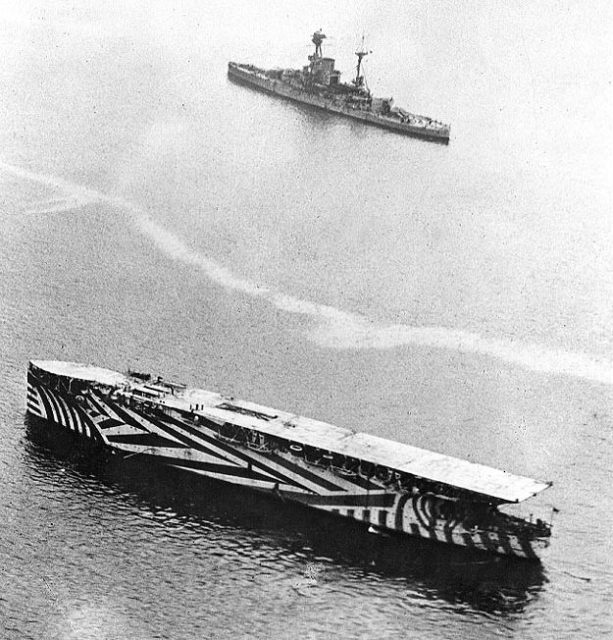

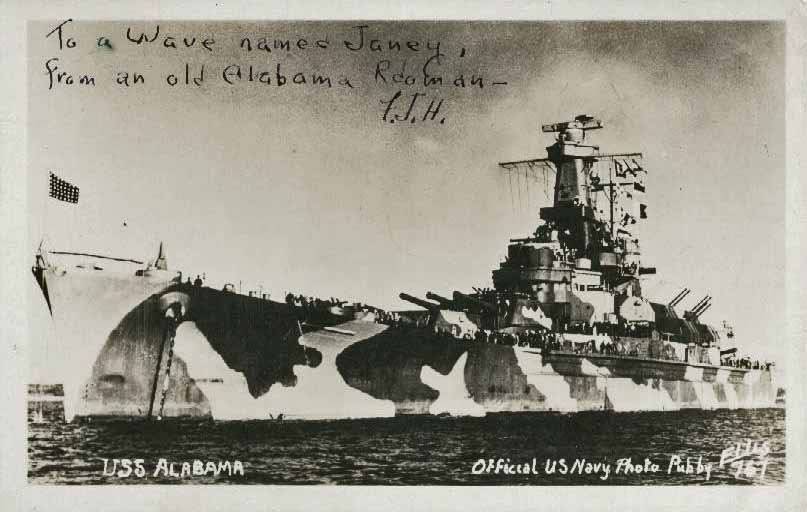

Rather than attempt to camouflage the ship, his idea was to camouflage the location and direction of the ship. To do this, he had ships painted in colorful geometric designs.

In the movies when a submarine is attacking a ship, the person using the periscope yells out, and someone pushes a button releasing the torpedo. In real life, it is much more complicated.

The sub could be no closer than about 10 feet and no farther away than just over 6,000 feet. The position of the ship and where it would be when the torpedoes were launched had to be estimated using the size, the usual speed of the ship, and the direction in which it was headed. This is where dazzle came into play. The bright colors, unusual shapes, and curved lines confused the eye, and it became very difficult to determine the shape, size, and direction of the ship.

According to SmithsonianMag, in May of 1917 the first dazzled ship, the HMS Industry, was sent out for a test. Local sailing ships and coastguards were to report back on the position. The dazzle worked brilliantly. After the initial test, about 400 troop ships were dazzled as well as 4,000 British merchant ships.

The designs painted on the ships closely resembled the Modernist art wave of the time, made popular by artists such as Picasso. Some of the painters of dazzle not only painted ships but put the same technique to canvas.

Over 100 years later, New York artist Tauba Auerbach created another dazzled ship. The New York Art Fund commissioned the artist to paint the fireboat, John J. Harvey.

As reported by ArtNet, Auerbach remarked, “I’m interested in the unlikely intelligence of dazzle camo. I like that it works to outsmart rather than hide. It’s like prioritizing ‘ingenuity over virtuosity,’ which is something I say to myself all the time in my head.” The boat was painted in what Auerbach calls “Flow Separation” and is displayed in various locations in New York Harbor where it will remain until May 2019, offering free weekend rides for those who are interested.

Artist Tobias Rehberger also designed a dazzle ship, the HMS President – a World War I era ship that may have been painted in dazzle during the war, which now sits at Somerset House on the River Thames in London, England. He also painted an entire café in dazzle, winning the Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennale.

Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez is another artist who dazzled a vessel, the Edmund Gardner, which sits in dry dock in Liverpool, England as a city monument.

Read another story from us: The Greatest Beer Run in History Happened During the Vietnam War

The Imperial War Museum in London has posters, clothing, pillows, tote bags and other items made with dazzle designs in honor of the imaginative designs created for the World War I ships.