In 1989, a respected wine merchant named William Sokolin made his way to a dinner at the luxurious Four Seasons restaurant in Manhattan, taking with him a wine bottle said to be from the collection of Thomas Jefferson. Sokolin had the Chateau Margaux valued at a mind-blowing $500,000, though some believe the price exaggerated. As dinner began, either Sokolin himself or a waiter accidentally knocked the bottle over and it smashed, leaving insurers with a hefty sum of $225,000 to pay. “I committed murder,” Sokolin told a reporter from The New York Times a few hours later.

Sokolin’s bottle of wine certainly rose to fame as being the most expensive ever that was never actually sold. While we frequently hear about some of the most expensive wines in the world, it is less often that we learn about the oldest ones. It is probably wise not to take wines as old as the Speyer wine, which is widely considered to be the oldest unopened bottle of wine on the planet, to a restaurant, or try to sell it at an auction—indeed, it is probably best to leave it unopened and displayed in a museum.

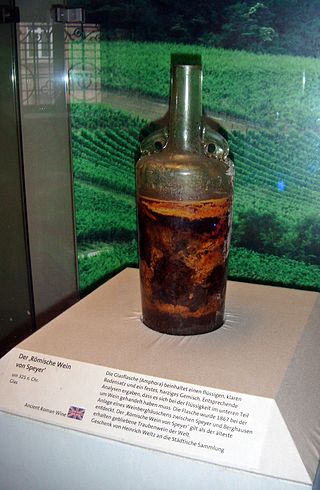

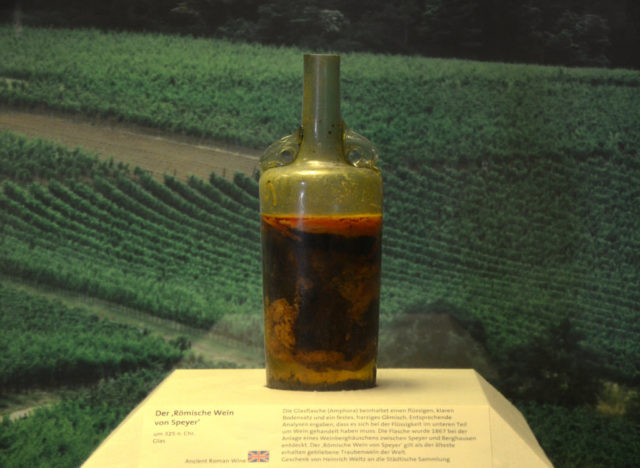

The age of the Speyer wine bottle is epic, estimated at around 1,650 years. Its makers did well by sealing it with hot wax and splashing it with olive oil, which is how the bottle, containing a presumably once drinkable white wine, has maintained the liquid inside it.

For many years, all kinds of experts have debated over what should be done with the Speyer bottle and whether it needs to be opened and analyzed at some point. However, the bottle has remained unopened as part of the Pfalz Historical Museum collection in the German City of Speyer.

Microbiologists have recommended not opening the wine and the same opinion was shared by the museum’s wine department curator, Ludger Tekampe, who in the past stated that if the bottle were to be opened, “We are not sure whether or not it could stand the shock of the air.”

The Speyer wine bottle is a rare artifact of the ancient world, one that helps us recall the earliest traditions of wine producing and consuming. This tradition was embedded well during the times of the ancient Greeks, a practice that was most certainly passed on from the East. In those early times, the ancient Greeks created a new deity, Dionysus, the god of the grape harvest, wine, and wine-making, and if somebody happened not to drink wine, the ancient Greeks would disregard them as being barbarians.

The cultural role of wine is even more evident in the case of Sparta, where, when Spartan boys were born, they were supposedly soaked in casks with wine. Spartans believed that bathing the babies in wine would increase their stamina. Each baby boy was further examined by the elderly members of the community. If a baby failed their test, he would allegedly be left to chance, either to die abandoned somewhere in the wilderness or to be saved by a stranger.

Wine cults smoothly continued in the days of Ancient Roma. Some books of history also tell us that the Romans even invented a technological device in Egypt’s Alexandria, one of their many provinces. This ancient gadgetry was used at social gatherings where all guests were invited to bring their own wine (this was one of the few known formats of Roman social events).

Supposedly, each guest would add their wine to the ancient machine, and the machine made sure that everyone drank only their own wine. This way, anyone who happened to bring a low-quality wine was discouraged to “steal” more refined wines from other guests.

These are just a few of the incalculable number of stories related to wine and why a bottle of wine can represent thousands of years of human history and customs. It was for this reason that finding the Speyer Wine in the grave of a Roman noble in 1867, in the Rhineland-Palatine region of Germany, was an event that caused such a stir. The antique bottle took its name from the city of Speyer, which was located in close proximity to the tomb it was found in.

The nobleman, along with his wife, had been buried there with the wine around 350 AD, and archaeologists were utterly baffled when they realized the bottle still contained liquid. To date, the wine is considered the earliest known liquid wine ever excavated from an archaeological site anywhere in the world.

The tomb where the Speyer wine bottle was found also contained two sarcophagi of the buried Roman spouses. There are numerous stories regarding the identity of the nobleman, one of which suggests that he was a Roman Legionnaire and that the bottle of wine was one of his provisions for his journey into the “afterlife,” which is probable given the burial customs then.

A chemist analyzed the Speyer bottle during World War I, but he did not dare to open it and after that, the wine was stored in the German museum in Speyer. While many scientists have hoped to obtain permission to analyze the bottle’s contents thoroughly, nobody has been granted one yet.

Perhaps this is for the best, since it may not be spoiled, but as one expert, Monika Christmann, commented, “It would not bring joy to the palate.”