Many thanks go to Doug Banks and his team – the masters of colourisation. The beauty of these colourised images is that colour, allows you to pick out and study the smallest detail. Do not click on their page – you will become addicted to their work It is the research that they do on each image that makes the captions themselves a history lesson.

The world’s first global conflict, the “Great War” pitted the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire against the Allied forces of Great Britain, the United States, France, Russia, Italy and Japan. The introduction of modern technology to warfare resulted in unprecedented carnage and destruction, with more than 9 million soldiers killed by the end of the war in November 1918.

Facebook page here WW1 Colourised Photos

9038 was later retrieved and in 1919 was sent to Russia as part of the White Russian Army but captured by the Red Russians on January 1st 1921.

(Photo source – Australian War Memorial collection E03832)

(Colourised by Joshua Barrett from the UK)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Painting-The-Past/891949734182777?fref=ts

(© IWM Q 1778)

(Colourised by Doug UK)

The fighting at Mouquet Farm was the site of nine separate attacks by three Australian divisions between 8 August and 3 September 1916. The farm stood in a dominating position on a ridge that extended north-west from the ruined, and much fought over, village of Pozieres. Although the farm buildings themselves were reduced to rubble, strong stone cellars remained below ground which were incorporated into the German defences. The attacks mounted against Mouquet Farm cost the 1st, 2nd and 4th Australian Divisions over 11,000 casualties, and not one succeeded in capturing and holding it. The British advance eventually bypassed Mouquet Farm leaving it an isolated outpost. It fell, inevitably, on 27 September 1916.

(Photo source © IWM Q 1417)

Photographer – Lt. Ernest Brooks

(Colorised by Gabriel Bîrsanu from Romania)

https://www.facebook.com/War-In-Colours-508317129316864/…

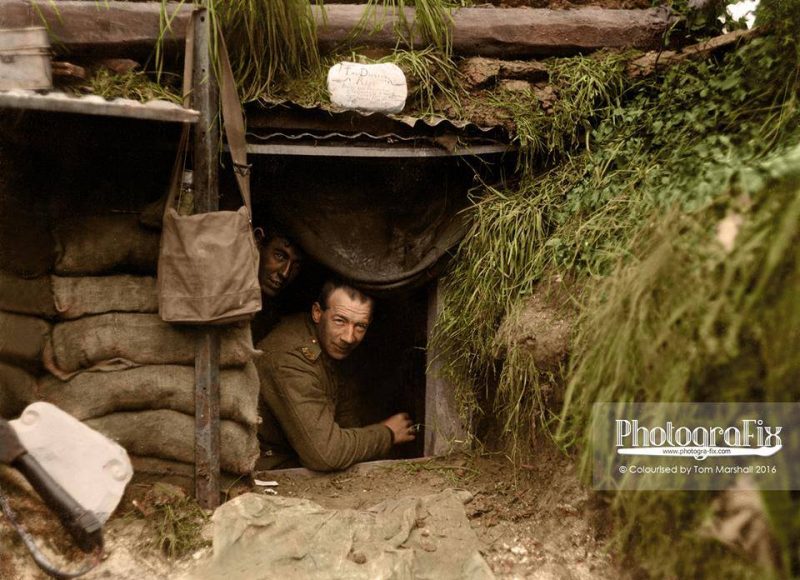

The sign above the entrance reads; “The Diggers Rest. Board and residence. Cold showers when it is wet. Herr Fritz’s Orchestra plays at frequent intervals.”

Hébuterne and its vicinity are of some significance in the history of New Zealand arms. Not only did the division finally arrest the German momentum there in March/April 1918, but it also became the start point of the Advance to Victory of August to November 1918.

Hébuterne was the place where Sergeant (later Major) Reginald Stanley Judson of the Auckland Regiment won the Distinguished Conduct Medal, to which in the space of a month he would add a Military Medal and then the Victoria Cross at Bapaume.

(text courtesy of christchurchcitylibraries.com)

(Photosource – National Library of New Zealand – H577)

Photographer Henry Armytage Saunders

© Colourised by Tom Marshall at PhotograFix – Restored and Colourised Photos 2016.

(Photo source – © IWM Q 29585)

(Colourised by Doug)

“…… the dressing station was pushed up to Achiet-le-Petit, and 500 casualties were passed through. Here three German medical officers presented themselves. One was the A.D.M.S. of a Naval Division; another, one of his staff; the third, Lt. Schnelling, of the 14th Bavarian Regiment. It transpired that this last was the medical officer who had been in charge of that cellar in Flers in which such ample personal correspondence, supplies, surgical instruments and medical comforts were found, these coming into Major Goldstein’s possession at that time……” (24th August 1918)

(Achiet-le-Petit is about 6kms from Bapaume)

(Colourised by Benjamin Thomas from Australia)

“On 5 September 1914 General Willcocks took command of the first divisions of Indian Army troops, on 26 September, just seven weeks after the declaration of war, two brigades of the 3rd Lahore Division landed at Marseilles, France. This was notwithstanding the delays caused by the activities of the German raiders Emden and Konigsburg and the slow transport ships. The Sihind brigade had been dropped off in Egypt to reinforce the garrison there and did not make it to the front until November 1914.”

“The Army of India was little understood by the general public and many thought that Indian brigades and divisions were composed of Sikhs and Gurkhas alone, without including the many other races of India. Nor were they aware that in each brigade was a British battalion.”

“The Army of India in 1914 was trained for frontier war or minor overseas expeditions, and for these purposes was to a certain extent sufficiently well armed and equipped, but it was by no means fully so. The two divisions which sailed from Karachi and Bombay had to have their equipment completed at Marseilles, at Orleans, and on the battle front itself. The artillery was only made up by denuding the guns of other divisions and the rifles could not fire the latest class of ammunition with which the British Army was supplied. As a result both rifles and ammunition had to be handed into store at Marseilles and fresh arms issued making things difficult for the troops as most soldiers trained and practised with this weapon to the exclusion of almost all others.”

“Under the Indian officers were the N.C.O.’s all of whom were in charge of a vast array of people from different backgrounds including: Rajputs, Jats, Pashtuns, Sikhs, Gurkhas, Punjabis, sappers from Chennai (Madras State), Dogras, Garhwalis and many others.”

(read more; http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2014/09/26/world-war-one-the-arrival-of-the-indian-army-in-france-1914-part-1/)

(Colorized by Marina Amaral from Brazil)

https://www.facebook.com/marinamaralarts/?fref=nf

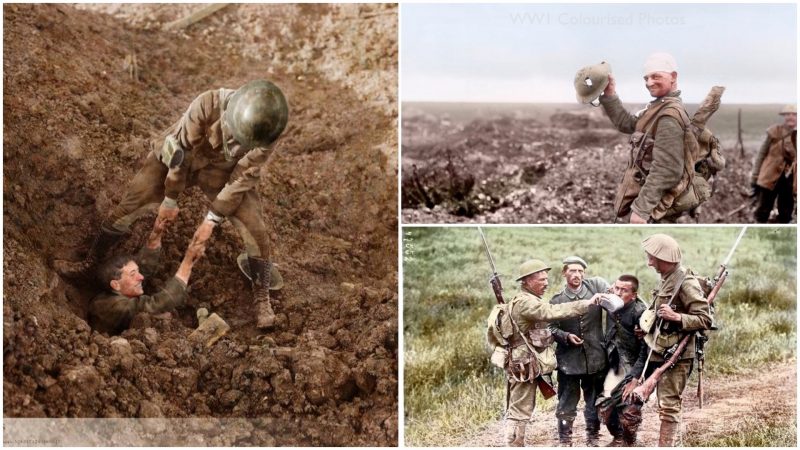

Battle of Flers-Courcelette. A stretcher borne wounded soldier waves his helmet (and leg) as he is carried in by German prisoners. Near Ginchy, 15th September 1916.

© IWM (Q 1321)

Photographer – Lt. Ernest Brooks

(Just a goodbye … happy Saint Valentine’s Day, young and old because love has no age.)

A soldier of the 71st Regiment Infantry, New York National Guard, says goodbye to his sweetheart as his regiment leaves for Camp Wadsworth, Spartanburg, South Carolina, where the Division is set to train for service, 1917.

(Colorised by Frédéric Duriez from France)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Histoire-de-Couleurs/695886770496139

“I have 3 volumes of ‘I Was There!’ from the 1930s, the issues came out weekly so at the end some readers were identifying people photographed . For this photo someone called W.Acott 6th Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment says the man on the left is stretcher bearer Jimmie Nye, later killed in action”.

Battle of Albert.

British infantrymen give a helping hand to wounded German prisoners near La Boisselle on 3 July 1916. They are both wearing their equipment in ‘fighting order’. One has an additional bandolier of ammunition, and each has an anti-gas PH (phenate hexamine) mask in a small bag hung at the front.

A first day objective, La Boisselle fell on 4 July.

The 6th moved to Baizieux on the 30th June and went into the reserve at Hencourt and Millencourt by mid morning on the 1st of July. They relieved the 8th Division at Ovillers-la-Boisselle that night and attacked at 3.15 the following morning with mixed success. On the 7th they attacked again and despite suffering heavy casualties in the area of Mash Valley, they succeeded in capturing and holding the first and second lines close to Ovillers. They were withdrawn to Contay on the 9th July. (wartimememoriesproject)

(Photo source – © IWM Q 758)

Photographer Lt. Ernest Brooks

(Colourised by Doug)

A Mark IV (Male) tank H45 ‘Hyacinth’ of H Battalion ditched in a German trench while supporting the 1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment, one mile west of Ribecourt. Some men of the battalion are resting in the trench, 20 November 1917.

Commanded by 2nd Lt. Jackson, H Btn, 24 Coy, 10 Sec. During the attack it reached the first objective of the day, The Hindenburg Line, before falling in the ditch. (additional info from John Winner)

(Photo source – © IWM Q 6433)

Photographer – Lt. John Warwick Brooke

(Colourised by Doug)

Note a camouflaged periscope.

A ‘Listening Post’ also commonly referred to as a ‘sap-head’, was a shallow, narrow, often disguised position somewhat in advance of the front trench line – that is, in No Man’s Land.

1/4th Battalion

August 1914 : in Blackburn. Part of East Lancashire Brigade in East Lancashire Division. Moved on mobilisation to Chesham Fold Camp (Bury) but sailed on 10 September 1914 from Southampton for Egypt.

26 May 1915 : formation became 126th Brigade, 42nd (East Lancashire) Division.

14 February 1918 : transferred to 198th Brigade in 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division, and absorbed 2/4th Bn. Renamed 4th Bn.

7 April 1918 : reduced to cadre strength.

16 August 1918 : transferred to 118th Brigade in 39th Division on Lines of Communication work.

(Photo source – © IWM Q 6473)

Photographer – Lt. John Warwick Brooke

(Colorised by Paul Kerestes from Romania)

https://www.facebook.com/jecinci/

In the early stages of the war, between a quarter to a third of recruits were rejected for service on account of dental defects.

The New Zealand Dental Association, seeing an opportunity to raise their profile, took up the challenge to treat these men and contribute to the war effort. They lobbied the Defence Force to create the first ever Dental Corps in November 1915, with the aim to have every soldier of the Expeditionary Force dentally fit for service. This was by no means an easy feat. Dental officers inspected the teeth of prospective soldiers in New Zealand mobilisation camps, and accompanied troops when they were mobilised overseas.

If the Army’s policy was to send a reinforcement of approximately two thousand healthy men each month, the work of the New Zealand Dental Corps (NZDC) was not to be underestimated. Between 1915 and 1918, they performed 221,214 filling operations and 98,817 teeth extractions.

The NZDC earned a reputation for mobility and efficiency. A dental hospital was set up only 5 kilometres from the front line on the Somme in September 1916. From ‘moral tooth brush drills’ at the camps to fillings, extractions and the treatment of the prevalent gum disease, ‘trench mouth’, the Dental Corps is thought to have saved the State around £19,000 per year.

Photograph taken by Henry Armytage Sanders.

Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, reference: 1/4-009512-G.

(Colourised by Richard James Molloy from the UK)

(Colourised by Nick Stone from the UK)

http://www.invisibleworks.co.uk/

Colourist Nick Stone,

“You start to doubt your sanity slightly when you spend an hour colouring in a photo brown that was, erm, brown, well sepia, but I’ve also tried to pull the detail out a bit as well.”

“…..you can see the scale of it, I realised as I worked on it you can see planks and joists as well as piles of brick rubble in quite a lot of detail, it becomes almost like a video game image, like some morsel of video intrigue from the 1990s, ‘Close Combat’, with it’s crawling terrified and tired men. There I suspect is one of the main problems we have in industrialised warfare, that game image and the fact that there’s real people in it down there somewhere too small to see while you’re pouring shells onto them or bombing them or now of course using missiles and drones.

Ploegsteert Wood, 22nd January 1918.

The soldier on the right in the white shirt has been identified as Driver – Alexander Henderson Priest (17822) from Collingwood, Victoria (demobbed in 1919 in good health)

(Photo source – Official Photo no.E4487)

Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office: W.L. Crowther Library

(Colorised by Frédéric Duriez from France)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Histoire-de-Couleurs/695886770496139

(Photo source – National Library of New Zealand

Photographer – Henry Armytage Sanders.

(Colorised by Benoit Vienne from France)

https://www.facebook.com/World-War-Colorisation-790508287736232/?fref=nf

August 1918

(Photo source – Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN No. 3395388)

(Colorised by Paul Kerestes from Romania)

https://www.facebook.com/jecinci/

A German sentry welcomes in the new year – 1918.

(Source image © Flickr ✠ drakegoodman ✠ Collection)

Colorised by Leo Courvoisier https://www.facebook.com/pages/Greetings-from-the-trenches/830845900362286?fref=nf

September 1916.

(Source – IWM Q1340)

Photographer – Lt. Ernest Brooks

(Colourised by Doug from the UK) https://www.facebook.com/ColouriseHistory?ref=hl

Carrier pigeons were used extensively during the First World War to relay messages over distances at relative speed and astonishing reliability.

Man-made communication devices were still largely un-reliable and crude at the time and as a result the duty of delivering news was pasted down to message runners, dogs and pigeons.

Pigeons excelled were runners could not. The job of a runner during the First World War was exceptionally dangerous as it required the soldier to leave his cover and run, often completely exposed to the enemy lines, between trenches. The fatality rates of runners were extremely high and there was little guarantee of messages reaching their intended destinations or knowing if they had if they did.

The small size of pigeons combined with their fast speed made them almost impossible for marksmen to shoot out of the sky, as a result birds of prey were often fielded by the enemy forces who let nature play out between the two.

After the introduction of tanks in the First World War, crews were equipped with a number of carrier pigeons as a means of keeping in touch with the outside world and relaying their position to friendly forces.

(Source – © IWM Q 9247)

(Colourised by Joshua Barrett from the UK)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Painting-The-Past/891949734182777?fref=ts

Toward the end of 1916, Germany introduced a new scheme called ‘Lozenge’ camouflage which was made up of polygons in four or five colors, sometimes more, printed on the fabric. This camouflage not only saved the weight of the paint, but also the time needed to apply it to each and every aircraft. Germany also had to develop camoflage schemes involving patterns that disrupted the silhouette of the plane making it difficult to distinguish the silhouette of the aircraft; the three to five colors they used were often quite similar to the ones printed on the “lozenge fabric”. (wwiaviation.com)

The Albatros D.V was a fighter aircraft used by the Luftstreitkräfte (Imperial German Air Service) during World War I. The D.V was the final development of the Albatros D.I family, and the last Albatros fighter to see operational service. Despite its well-known shortcomings and general obsolescence, approximately 900 D.V and 1,612 D.Va aircraft were built before production halted in early 1918. The D.Va continued in operational service until the end of the war.

In April 1917, Albatros received an order from the Idflieg (Inspektion der Fliegertruppen) for an improved version of the D.III. The prototype flew later that month. The resulting D.V closely resembled the D.III and used the same 127 kW (170 hp) Mercedes D.IIIa engine. The most notable difference was a new fuselage which was 32 kg (70 lb) lighter than that of the D.III. The elliptical cross-section required an additional longeron on each side of the fuselage. The prototype D.V retained the standard rudder of the Johannisthal-built D.III, but production examples used the enlarged rudder featured on D.IIIs built by Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke (OAW). The D.V also featured a larger spinner and ventral fin.

(skytamer.com)

(Colorised by Frédéric Duriez from France)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Histoire-de-Couleurs/695886770496139

The back of a canvas and steel tree observation post, near Souchez, Pas-de-Calais, France. 15 May 1918.

Trying to hide yourself in No Man’s Land during the war was a risky business. The badly damaged landscape gave no real cover from the watching eyes on either side. Therefore, the ability to spy on the opposite trenches whilst remaining hidden was highly valuable.

To achieve this, both sides began to develop Observation Post Trees (O. P. Trees) made of iron, canvass and sheet metal. Designed to replicate the shell splintered trees that existed in No Man’s Land, these observation posts were originally constructed behind the lines. Then, once they were nearing completion, during the darkest nights engineers would cut down or remove existing trees and replace them with the false one.

From these fake trees observers and snipers were now able to watch the enemy whilst effectively hiding in plain sight. The British Army used around 45 Observation Post Trees during the conflict with the first being placed near Ypres. (eastsussexww1.org.uk)

(Source © IWM Q 10308)

McLellan, David (Second Lieutenant) (Photographer)

Colorised by Leo Courvoisier https://www.facebook.com/pages/Greetings-from-the-trenches/830845900362286?fref=nf

September 1916.

(Source – IWM Q1340)

Photographer – Lt. Ernest Brooks

(Colourised by Doug from the UK) https://www.facebook.com/ColouriseHistory?ref=hl

Holmes was 19 years old, when as a private serving with the 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles, Canadian Expeditionary Force, he won the Victoria Cross. On 26 October 1917 near Passchendaele, Belgium, he performed a deed for which King George V awarded Tommy the Victoria Cross: “when the right flank of the Canadian attack was held up by heavy machine-gun fire from a pill-box strong point and heavy casualties were producing a critical situation, Private Holmes, on his own initiative and single-handed, ran forward and threw two bombs, killing and wounding the crews of two machine-guns. He then fetched another bomb and threw this into the entrance of the pill-box, causing the 19 occupants to surrender.”

It was during the investiture at Buckingham Palace that Holmes admitted to King George V that he had lied about his age and joined the army at age 17.

Sergeant Tommy Holmes, VC, returned to Owen Sound after the war to great fanfare and receiving a hero’s welcome. On 16 September 1919, he was chosen to be part of the Colour Party for the laying-up of the 147th (Grey) Battalion, CEF Colours in the Carnegie Library, Owen Sound.

Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan #3216874

He is listed in the source as being the youngest Canadian recipient of the VC, however there is another Canadian VC, Thomas Ricketts from Newfoundland who was younger. However, Newfoundland wasn’t part of the Canadian confederation at that point…

(Colourised by Mark at Canadian Colour)

https://www.facebook.com/canadiancolour

105mm M14 lFH Skoda – was the standard Light Field Howitzer of the Austria-Hungarian Army and was also used by Germany.

(Photo source: bildarchivaustria – WK1/ALB051/13945)

(Colorised by Frédéric Duriez from France)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Histoire-de-Couleurs/695886770496139