Butter as a sculpting medium was a tradition most associated with the Renaissance and Baroque periods and can be traced back to “banquet art.” In the same vein as sugar art, it was a way of bringing entertainment to the table and usually signified a special occasion or part of the meal. The earliest reference to the practice dates from 1536 and details the creations of Pope Pius V’s cook Bartolomeo Scappi, among which could be found an elephant and a tableau of Hercules engaged in combat with a lion.

The earliest pieces in the modern sense as public art date from c. 1870s America, created by Caroline Shawk Brooks, a farm woman from Helena, Arkansas. She showed her artistic talents as a young child, enjoying painting and drawing. Her first sculpting project, modeled in clay from a creek, was Dante’s head. At the age of twelve, she won a medal for her wax flowers.

Brooks was the first known American sculptor working in the medium of butter, and she would come to be identified as “The Butter Woman”. In 1867, she created her first butter sculpture, when, after the failure of the farm’s cotton crop, she sought a source of supplemental income. Rather than traditional sculpting tools, she used “common butter-paddles, cedar sticks, broom straws and camels hair pencils”.

Her customers appreciated the skillfully sculpted butter, and there was a good market for her works. She continued producing her butter sculptures for about a year and a half, then took a break for a few years. Brooks resumed making butter art in 1873 when she created a bas-relief portrait, which she donated to a church fair.

Working with, transporting, and exhibiting butter sculptures presented Brooks with a unique set of challenges. Brooks had overcome the major disadvantage of butter as a medium by simply by using ice. To preserve her delicate butter sculptures, she created them in flat metallic milk pans, which she set in larger pans filled with ice.

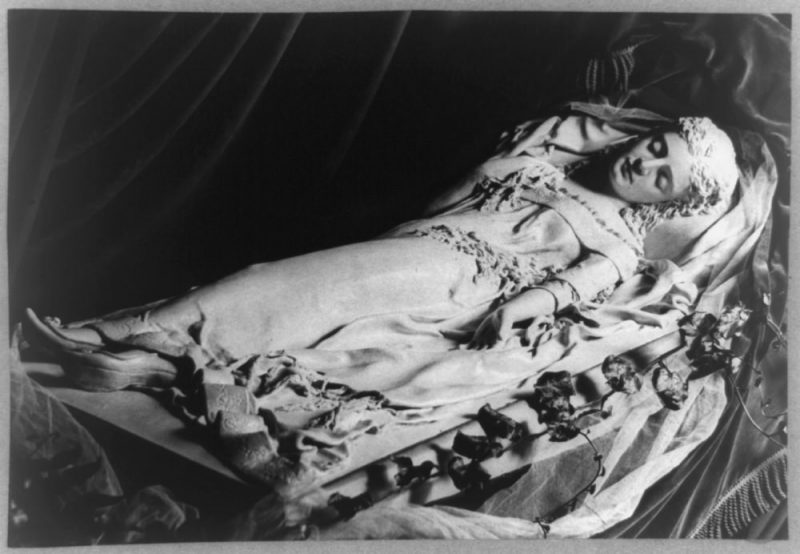

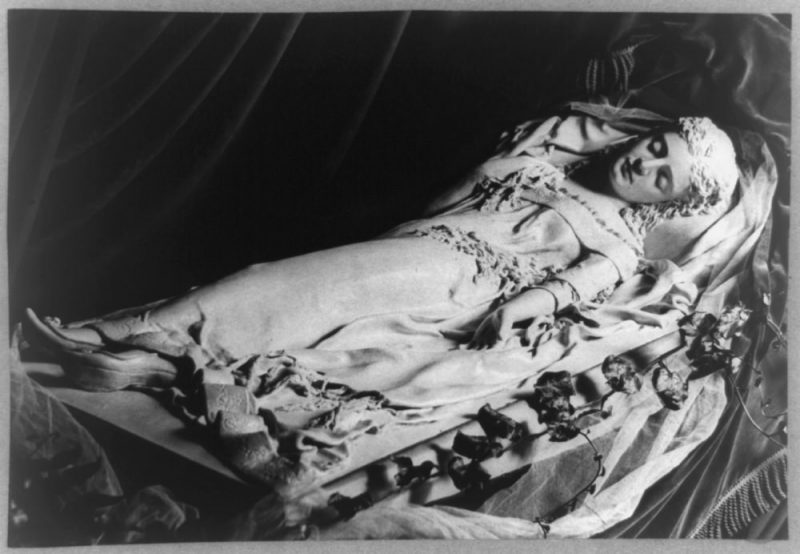

In 1873, she made a sculpture of the blind princess Iolanthe from Danish poet and playwright Henrik Hertz’s verse drama King René’s Daughter. Dreaming Iolanthe, as it was known, was exhibited at a Cincinnati gallery in 1874 for two weeks and attracted more than two thousand people keen to catch a glimpse of the sleeping princess.

Four years later, in 1878, she opened a Washington, D.C. studio and sculpted a life-size version of Dreaming Iolanthe in butter, and shipped it to be exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. She found it amusing that customs officials had listed her sculpture not as a work of art, but as “110 lbs. of butter”.

After preserving her original butter Dreaming Iolanthe for a half a year, she desired a method which would not require keeping it in cold storage. She mixed up some plaster and poured it onto the butter sculpture, without knowing ahead of time what the results may be. The plaster quickly set, and she cut a hole in the bottom of the milk pan which held her creation.

Brooks then set the pan over a container of boiling water, and the butter melted and drained out of the hole. She removed the remainder of the bottom of the pan and was left with a greased plaster negative. She placed more plaster inside and, after some difficulty removing the outer layer, was left with a successful plaster positive.

Caroline Shawk Brooks received a patent in 1877 for her process of creating lubricated plaster molds. However, she did not use plaster casts to reproduce her butter sculptures, instead preferring to sculpt a new one for each exhibit.