Edward Sheriff Curtis was an American ethnologist and photographer best known for his amazing project “The North American Indian” that consist of a vast photo collection of the American West and of Native American peoples.

In 1906, J. P. Morgan provided Curtis with $75,000 to produce a series on Native Americans. This work was to be in 20 volumes with 1,500 photographs. He took over 40,000 photographic images from over 80 tribes. He recorded tribal lore and history, and he described traditional foods, housing, garments, recreation, ceremonies, and funeral customs. He wrote biographical sketches of tribal leaders, and his material, in most cases, is the only written recorded history, although there is still a rich oral tradition that documents tribal history.

He worked extensively with ethnographer and British Columbia native George Hunt in 1910, which inspired his work with the Kwakiutl, but much of their collaboration remains unpublished

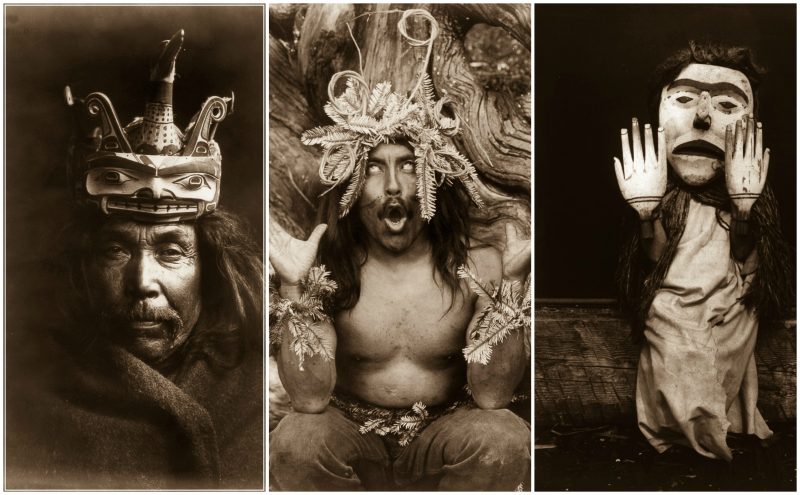

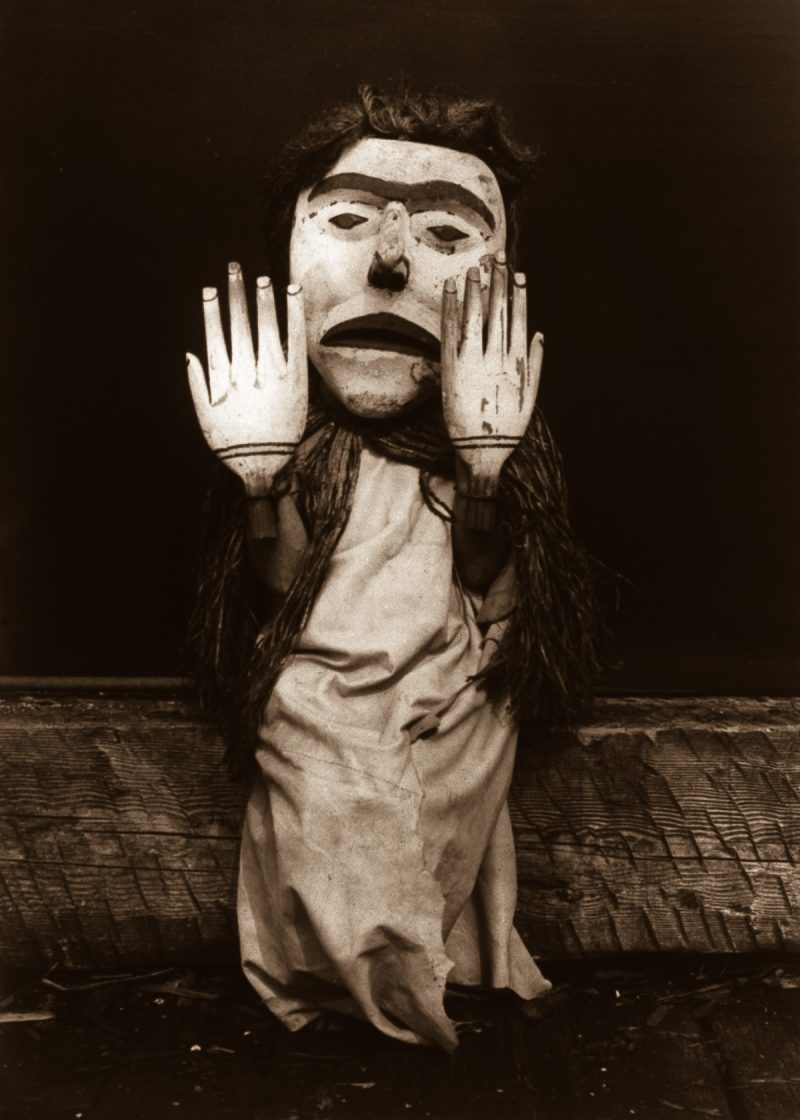

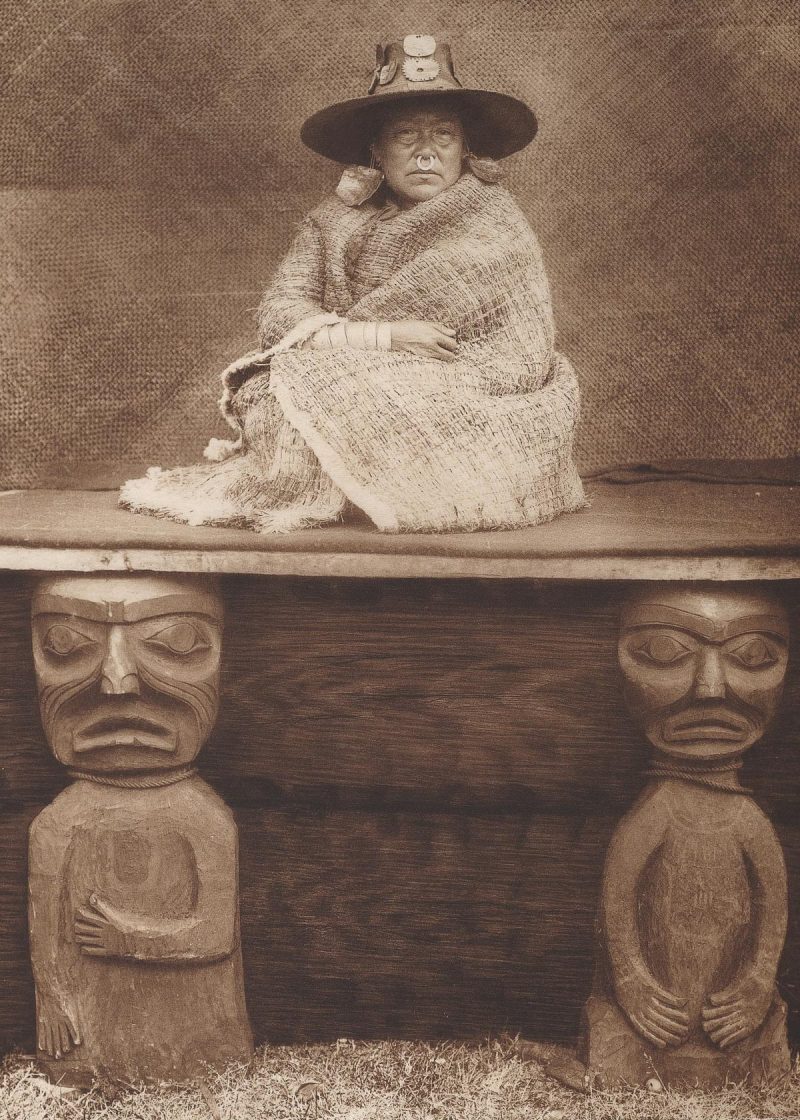

Here, we selected amazing photos from the Kwakiutl tribe or originally known as the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw.

The Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw are a Pacific Northwest Coast indigenous people. Their current population is approximately 5,500. Most live in British Columbia, on northern Vancouver Island and the adjoining mainland, and on islands around Johnstone Strait and Queen Charlotte Strait. Some also live outside their homelands in urban areas such as Victoria and Vancouver.

Kwakwaka’wakw oral history says their ancestors (‘na’mima) came in the forms of animals by way of land, sea, or underground. When one of these ancestral animals arrived at a given spot, it discarded its animal appearance and became human. Animals that figure in these origin myths include the Thunderbird, his brother Kolus, the seagull, orca, grizzly bear, or chief ghost. Some ancestors have human origins and are said to come from distant places.

Historically, the Kwakwaka’wakw economy was based primarily on fishing, with the men also engaging in some hunting, and the women gathering wild fruits and berries. Ornate weaving and woodwork were important crafts, and wealth, defined by slaves and material goods, was prominently displayed and traded at potlatch ceremonies. These customs were the subject of extensive study by the anthropologist Franz Boas. In contrast to most non-native societies, wealth and status were not determined by how much you had, but by how much you had to give away. This act of giving away your wealth was one of the main acts at a potlatch.

Kwakwa’wakw society was organized into four classes: the nobility, attaining through birthright and connection in lineage to ancestors, the aristocracy who attained status through connection to wealth, resources, or spiritual powers displayed or distributed in the potlatch, commoners, and slaves. On the nobility class, “the noble was recognized as the literal conduit between the social and spiritual domains, birthright alone was not enough to secure rank: only individuals displaying the correct moral behavior [sic] throughout their life course could maintain ranking status.”

The first documented contact was with Captain George Vancouver in 1792. Disease, which developed as a result of direct contact with European settlers along the West Coast of Canada, drastically reduced the indigenous Kwakwaka’wakw population during the late 19th-early 20th century. Kwakwaka’wakw population dropped by 75% between 1830 and 1880.

All Images by Edward.S. Curtis, Library of Congres