Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot was a French inventor who experimented with working models of steam-engine-powered vehicles for the French Army, intended for transporting cannons, starting in 1765. He is known to have built the first working self-propelled mechanical vehicle, the world’s first automobile. He was one of the first to employ successfully, a device for converting the reciprocating motion of a steam piston into rotary motion by means of a ratchet arrangement.

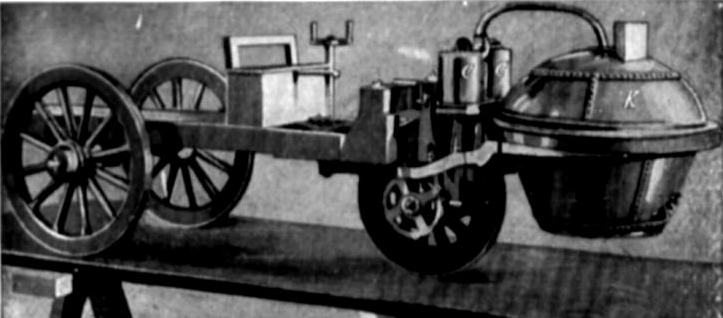

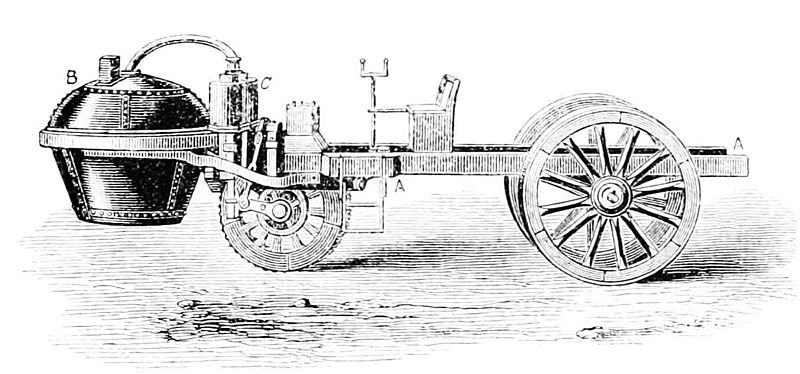

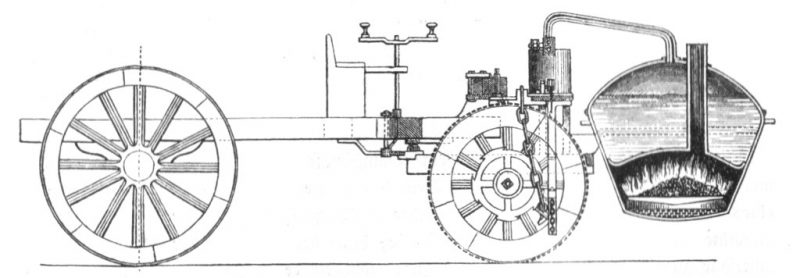

His “machine à feu pour le transport de wagons et surtout de l’artillerie” (“fire engine for transporting wagons and especially artillery”) was built from 1769 in two versions for use by the French Army. A small version of his three-wheeled fardier à vapeur (“steam dray”) ran in 1769. (A fardier was a massively built two-wheeled horse-drawn cart for transporting very heavy equipment such as cannon barrels).

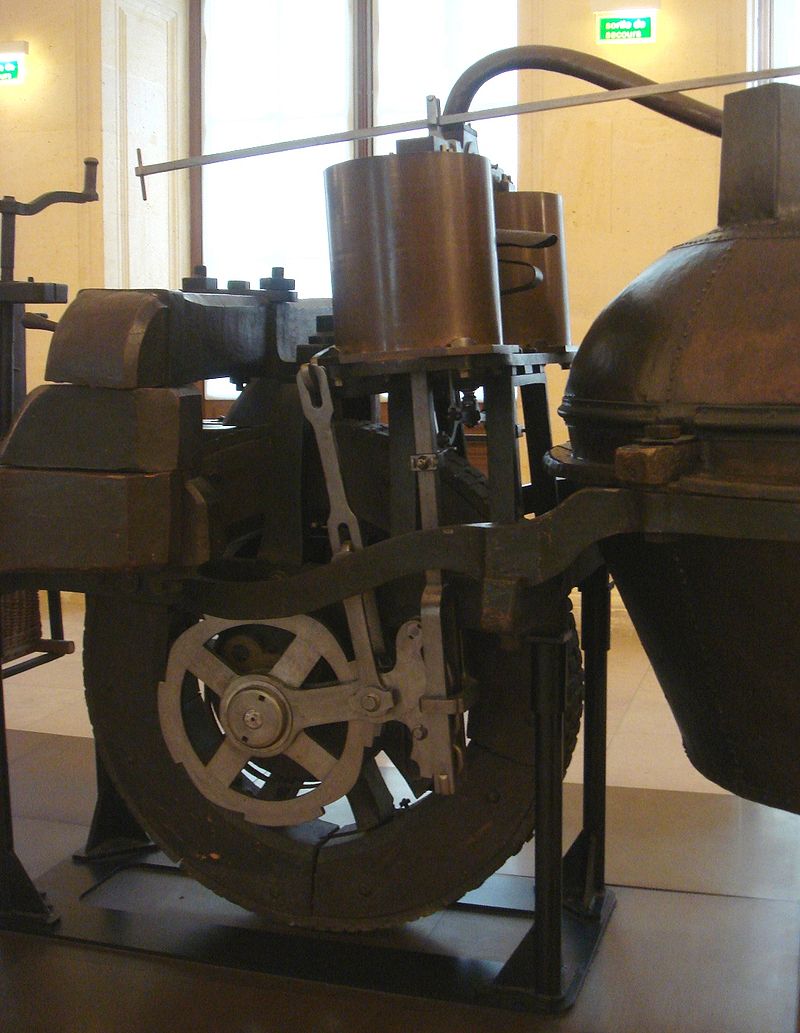

One year later, in 1770, a full-size version of the fardier à vapeur was built, specified to be able to carry 4 tons and cover 2 lieues (7.8 km or 4.8 miles) in one hour, a performance it never achieved in practice. The vehicle, which weighed about 2.5 tonnes tare, had two wheels at the rear and one in the front where the horses would normally have been; this front wheel supported the steam boiler and driving mechanism. The power unit was articulated to the “trailer” and steered from there by means of a double handle arrangement. One source states that it seated four passengers and moved at a speed of 2.25 miles per hour(3.6 km/h).

However, it remained a short-lived experiment due to inherent instability and the vehicle’s failure to meet the Army’s specified performance level. The vehicle was reported to have been very unstable due to poor weight distribution – which would have been a serious disadvantage seeing that it was intended that the fardier should be able to traverse rough terrain and climb steep hills. In 1771, the second vehicle is said to have gone out of control and knocked down part of the Arsenal wall, (reported to be the first known automobile accident); however according to Georges Ageon, the earliest mention of this occurrence dates from 1801 and it does not feature in contemporary accounts. Boiler performance was also particularly poor, even by the standards of the day, with the fire needing to be relit and steam raised again every quarter of an hour or so, considerably reducing overall speed.

After running a small number of trials variously described as being between Paris and Vincennes and at Meudon, the project was abandoned and the French Army’s experiment with mechanical vehicles came to an end. Even so, in 1772, King Louis XV granted Cugnot a pension of 600 livres a year for his innovative work and the experiment was judged interesting enough for the fardier to be kept at the Arsenal until transferred to the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in 1800, where it can still be seen today.

241 years later, in 2010, a copy of the “fardier de Cugnot” was built by some of the pupils of the Arts et Métiers ParisTech, a French Grande école, and the city of Void-Vacon. This replica worked perfectly, proving that the concept was viable, and the truth of the tests done in 1769. This replica was exhibited in 2010 at the Paris Motor Show. It is now visible at the native village of Cugnot, at Void-Vacon (Meuse), and exhibited by a local association.

With the French Revolution, Cugnot’s pension was withdrawn in 1789, and the inventor went into exile in Brussels, where he lived in poverty. Shortly before his death, he was invited back to France by Napoleon Bonaparte and eventually returned to Paris, where he died on 2 October 1804.