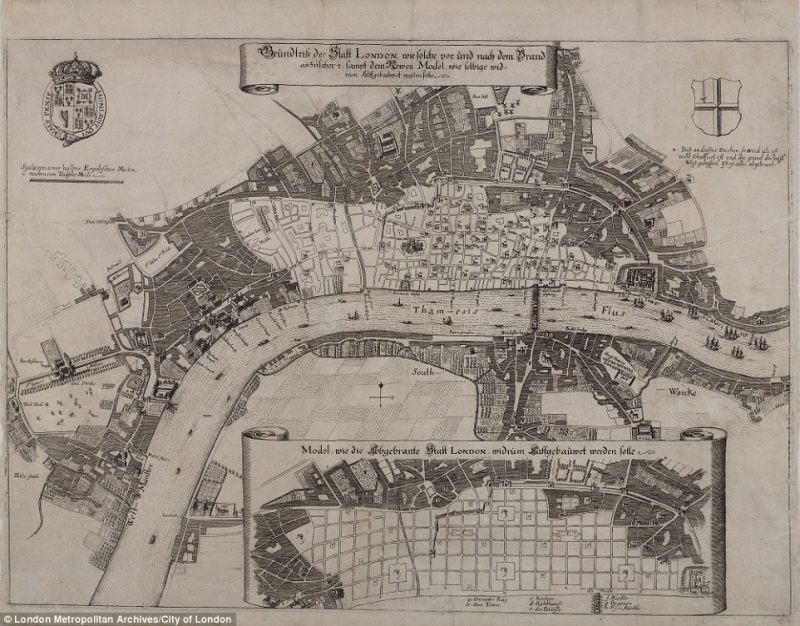

For centuries, the city of London has been constantly reminded of the terrible fire that destroyed over one-third of the city. In 1666, the fire started at a bakery on Pudding Lane on an early Sunday morning. In just five days 13,200 houses, 87 churches, many official buildings, and St. Paul’s Cathedral were all eaten by the flames. The authorities at the time had to think of a plan for rebuilding the parts of the city after what would be called the Great Fire of London.

As devastating as the incident was, many people in the city saw this as a good opportunity to rebuild what was ruined. They would eventually have a gorgeous, modern city if they chose to rebuild.

Photo Credit: London Metropolitan Archives

There had been several master plans brought forward by the architects in the city. Those masterplans have now gone on display to reveal to London’s current citizens just how different their city might look if those plans had been approved.

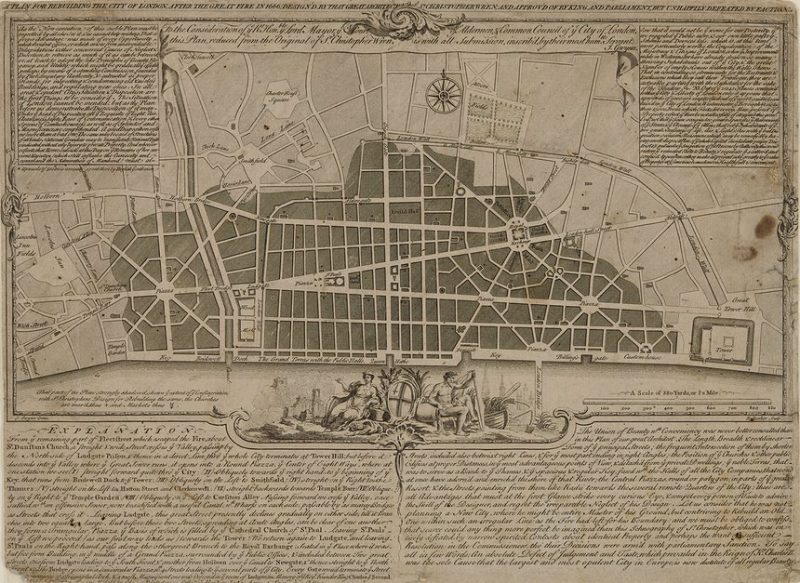

One of the architects, Christopher Wren, had an idea to re-organize London’s streets. His plans were very much influenced by Paris’ design. He had proposed that London should be rebuilt with grand formal streets, classical buildings, and even sweeping plazas.

Seeing these different ideas, King Charles II had encouraged other young men to put their ideas on paper and submit them like Wren had. One of the proposals was John Evelyn’s; he had favored the idea of adopting the Italian-style piazzas and broad avenues in his master plan.

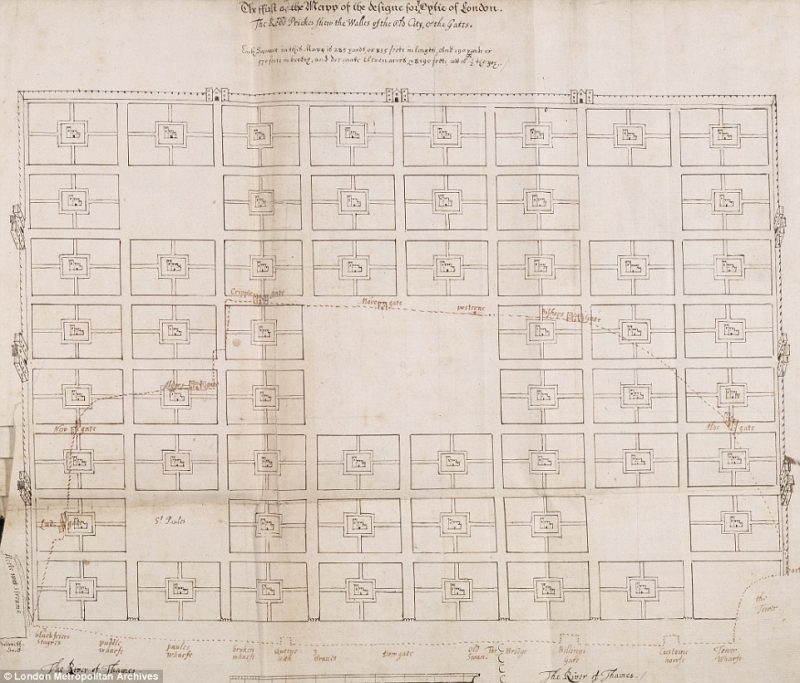

Richard Newcourt had, unknowingly at the time, proposed a new radical plan to use a grid system to map out the city. His idea of the grid system would later be used by United States cities like Philadelphia.

A scientist and architect, Robert Hooke, had also proposed a grid pattern complete with wide boulevards. His grid system and ideas would later be used for Paris’ renovation and in Liverpool.

Captain Valentine Knight had proposed building two main streets running east to west and eight running north to south. Between the streets there would be narrow blocks of houses connected by the smaller lanes. He also had an idea of a canal loop to the River Fleet.

Obviously, none of these plans were ever pushed through due to the fact that there was much fighting over the ownership of the land, and also because there was a lack of finances. Some of the plans were rather brilliant, as stated above.

Because of the fighting, and after hearing all of the competitive claims, the Fire Court left the city’s plans as they had been. The only changes that were made is that the streets were widened and straightened, and bottlenecks were eased.

There were only a few new things built. One was a street named King Street and another was special market halls which were created for those who had been living on the streets.

Knight’s plan of building the fleet into a canal was started, but it failed after a few decades of building. It failed because the plan to build a new Quay from Blackfriars had also failed, resulting in their quitting while they were ahead and not wasting any more money on the project.

As stated above, each and every architect’s plans were largely different from the next. London could have appeared quite different if people would have agreed on one of those plans. The plans are now in a new exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects in London. The title of the exhibition is called Creation from Catastrophe: How Architecture Rebuilds Communities.

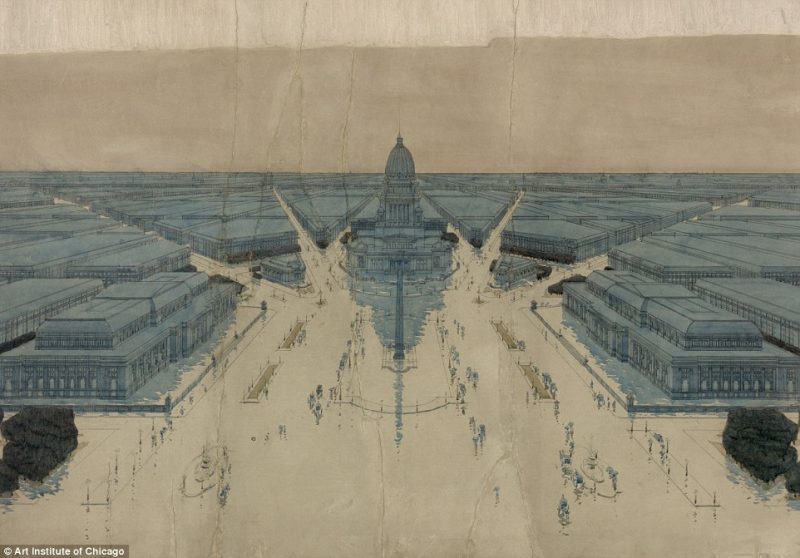

The exhibition also includes master plans for Chicago after their Great Fire of 1871, and Lisbon after the Portuguese city was destroyed by an earthquake in 1755. Other parts of the exhibition show newer solutions, such as the attempt to build bamboo homes in Pakistan and floating buildings for overcoming the flooding of Lagos, Nigeria.

Before the exhibition was opened, there was a statement from the museum that they would showcase five alternative plans for London that were produced after the Great Fire. The exhibition will also take visitors through other drastic events that happened to cities, such as 18th-century Lisbon, 19th-century Chicago, 20th-century Skopje, and winding up in the countries of Nepal, Nigeria, Japan, Chile, Pakistan, and the United States.

Photos Credit: London Metropolitan Archives