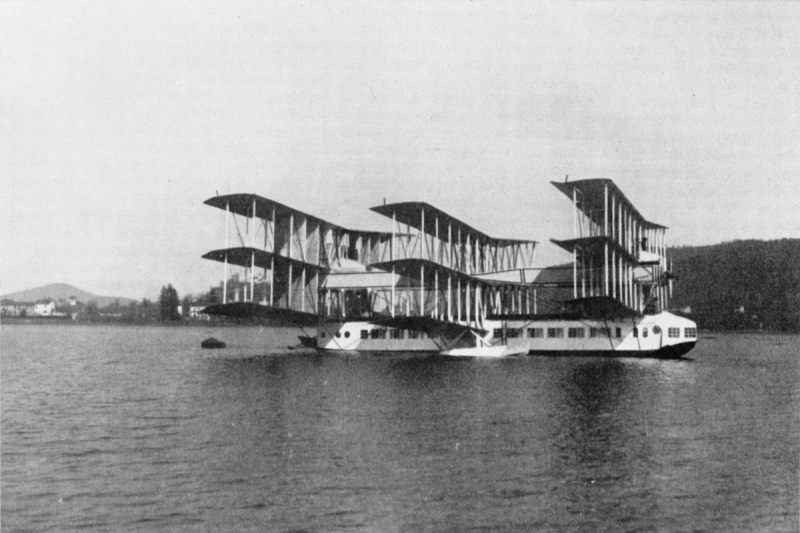

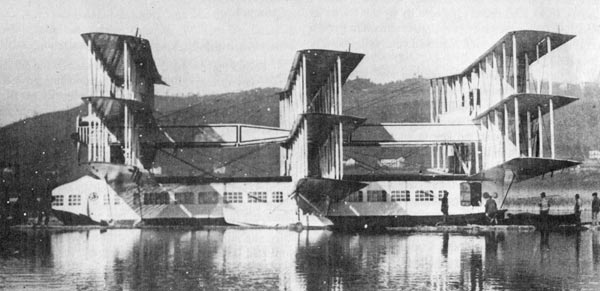

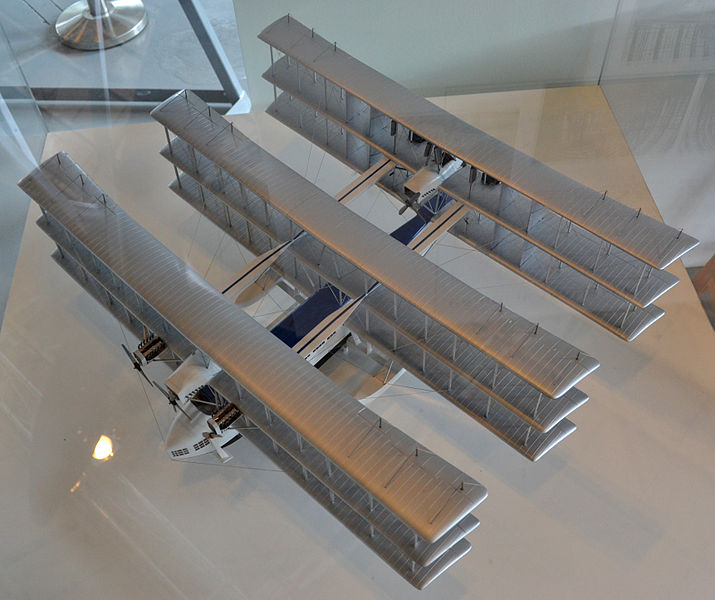

The Caproni Ca.60 Transaereo, often referred to as the Noviplano (nine-wing) or Capronissimo, was the prototype of a large nine-wing flying boat intended to become a 100-passenger transatlantic airliner. Only one example of this aircraft, designed by Italian aviation pioneer Gianni Caproni, was built by the Caproni company. It featured eight engines and three sets of triple wings.

The idea of a large multi-engined flying boat designed for carrying passengers on long-range flights was considered, at the time, rather eccentric. Caproni thought, however, that such an aircraft could allow the travel to remote areas more quickly than ground or water transport, and that investing in innovative aerial means would be a less expensive strategy than improving traditional thoroughfares. He affirmed that his large flying boat could be used on any route, within a nation or internationally, and he considered operating it in countries with large territories and poor transport infrastructures, such as China.

In spite of criticism from some important figures in Italian aviation, especially aerial warfare theorist Giulio Douhet, Caproni started designing a very innovative aircraft and soon, in 1919, he took out a patent on it.

The construction of the model 3000, or Transaereo, began in the second half of 1919. The earliest reference to this event is found in a French daily newspaper of August 10, 1919, and perhaps the first parts were built in the Caproni factory of Vizzola Ticino. In September, an air fair took place at the Caproni factory in Taliedo, not far from Milan, during which the new, ambitious project was heavily publicized. Later in September, Caproni experimented with a Caproni Ca.4 seaplane to improve his calculations for the Transaereo. In 1920, the huge hangar where most of the construction of the Transaereo was to take place was built in Sesto Calende, on the shore of Lake Maggiore.

It was a large flying boat, whose main hull, which contained the cabin, hung below three sets of wings each composed of three superimposed aerodynamic surfaces: one set was located fore of the hull, one aft and one in the center (a little lower than the other two). Each set of three wings was obtained by the direct reuse of the lifting surfaces of the triplane bomber Caproni Ca.4; after the end of the war, several aircraft of this type were cannibalized in order to build the Transaereo.

The wingspan of each of the nine wings was 30 m (98 ft 5 in), and the total wing area was 750.00 m² (8073 ft²); the fuselage was 23.45 m (77 ft) long and the whole structure, from the bottom of the hull to the top of the wings, was 9.15 m (30 ft) high. The empty weight was 14,000 kg (30,865 lb) and the maximum takeoff weight was 26,000 kg (57,320 lb). The fuel tanks were located in the cabin roof, close to the central wing set. Fuel reached the engines thanks to wind-driven fuel pumps. The aircraft was powered by eight Liberty L-12 V12 engines built in the United States. Capable of producing 400 hp (294 kW) each, they were the most powerful engines produced during the First World War.

The passenger cabin was enclosed and featured wide panoramic windows. Travelers were meant to sit in pairs on wooden benches that faced each other—two facing forward and two backward. The open-air cockpit accommodated a pilot in command and a co-pilot side-by-side. Its floor was raised above the passenger cabin floor so that the shoulders and heads of the pilots protruded through the roof. The flight deck could be reached from inside the fuselage by a ladder.

On January 10, 1921, the forward engines and nacelles were tested, and no dangerous vibrations were recorded. On January 12 two of the aft engines were also successfully tested. On 15, Caproni forwarded his request for permission to undertake test flights to the Inspector General of Aeronautics, General Omodeo De Siebert.

The second flight took place on March 4. Semprini accelerated the aircraft to 100 or 110 km/h (54–59 kn, 62–68 mph), pulling the yoke toward himself; suddenly the Transaereo took off and started climbing in a sharp nose-up attitude; the pilot reduced the throttle, but then the aircraft’s tail started falling and the aircraft lost altitude, out of control. The tail soon hit the water and was rapidly followed by the nose of the aircraft, which slammed into the surface, breaking the fore part of the hull. The fore wing set collapsed in the water together with the nose of the aircraft, while the central and the aft wing sets, together with the tail of the aircraft, kept floating. The pilot and the flight engineers escaped the wreck unscathed.

Most of the damaged structure of the wreck was lost after the Transaereo project was eventually abandoned.

Caproni, however, was convinced of the importance of preserving and honoring the historical heritage related to the birth and early development of Italian aviation in general, and to the Caproni firm in particular.

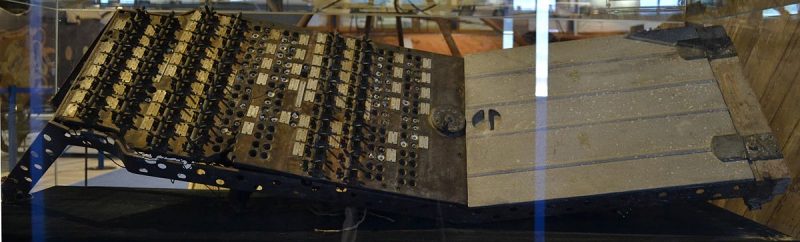

His historical sensibility meant that several parts of the Transaereo, retrospectively known as the Caproni Ca.60, survived: the two outriggers, the lower front section of the main hull, a control and communication panel and one of the Liberty engines were spared and, after following the Caproni Museum in all its whereabouts between its foundation in 1927 and its move to its current location in Trento in 1992, they were displayed together with the rest of the permanent collection in the main exhibition hall of the museum in 2010.

A section of one of the two triangular truss-booms also survived, as well as one of the hydrofoils that connected the main hull and the outriggers. These fragments are on display at the Volandia aviation museum, in the Province of Varese, hosted in the former industrial premises of the Caproni company at Vizzola Ticino.