Faced with a daunting and unfamiliar situation, many did what they had to do to overcome the hardships of World War One. Women, in particular, were able to do much to support the war effort at home and abroad; sometimes even as spies.

But no one offered to use her feminine wiles to infiltrate enemy lines and gather information from the enemy as flamboyantly as Margaretha Zelle, better known as Mata Hari.

She was born to Adam Zelle and Antje van der Meulen, a wealthy couple from the Netherlands. Her father was a successful businessman; his lucrative investments in oil enabled him to send his children to exclusive schools, one of which Margaretha attended until the age of thirteen. When her father declared bankruptcy in 1889, her parents divorced and, tragically, two years later her mother died. Her father remarried in 1893, but the family did not stay together.

Margaretha moved in with her godfather. She enrolled in a school in Leiden, a Dutch province of Southern Holland, and was studying to be a kindergarten teacher. However, due to advances she received from the headmaster, her godfather removed her from the school. She ran away from her godfather and went to stay with her uncle in The Hague.

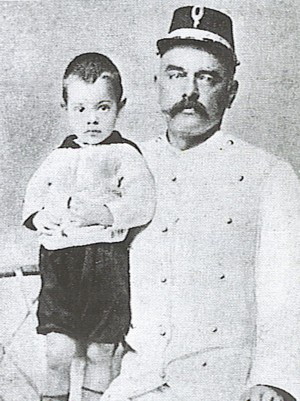

When Margaretha turned 18, she answered an ad in a newspaper from the wealthy Captain Rudolf MacLeod in the Dutch Colonial Army, who was advertising for a wife. In 1895, she and the Captain were married in the Netherlands; this placed her back into the Dutch upper class. The Captain had been living on the island of Java, and the couple returned there, where Margaretha soon gave birth to two children, Norman-John MacLeod in 1897, and Louise Jeanne MacLeod in 1898.

She was not happy in her marriage, as the Captain was an abusive alcoholic who, according to local tradition, openly kept a concubine. Margaretha left her husband and temporarily moved in with a Dutch officer. During this time she studied dance and Indonesian customs and came up with her stage name of Mata Hari.

The Captain promised to change if Margaretha returned to him, but he was soon back to his old ways.

In 1899, both children became seriously ill. Many believed the children were poisoned by enemies of their father, while others said they suffered from syphilis contracted from their father, who had passed it on to Margaretha. Norman-John passed away at the age of two, but Louise Jeanne survived the illness.

After the death of their son, the couple moved back to the Netherlands. In August of 1902, Margaretha and the Captain officially separated and finalized their divorce in 1906, with Margaretha gaining custody of Louise Jeanne. The Captain never paid child support, which made life difficult for Margaretha.

After one of the arranged visits with his daughter, Macleod refused to give the child back to her mother. Women had very few rights concerning their children at that time, and Margaretha was unable to get her daughter back. Louise Jeanne never was returned to her mother and, sadly, died at the age of twenty-one, possibly from complications of syphilis. Margaretha moved to Paris in 1903 and performed as a horsewoman in a circus and as an artist’s model. She originally used her married name, much to the chagrin of her former in-laws. Within two years, she had made a name for herself as an exotic dancer.

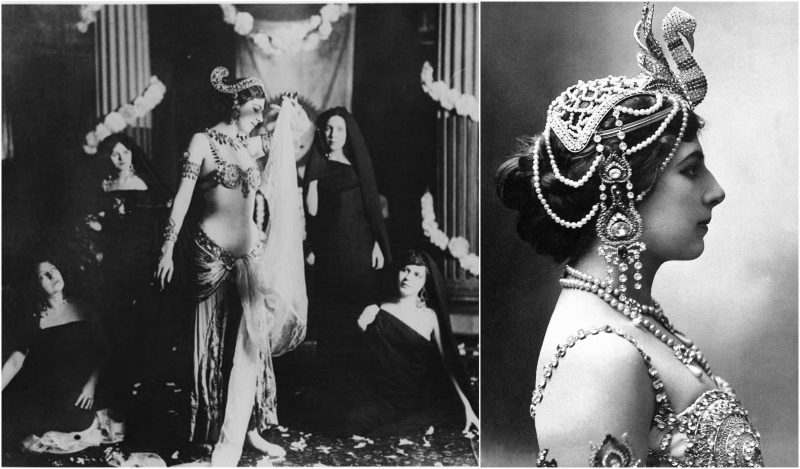

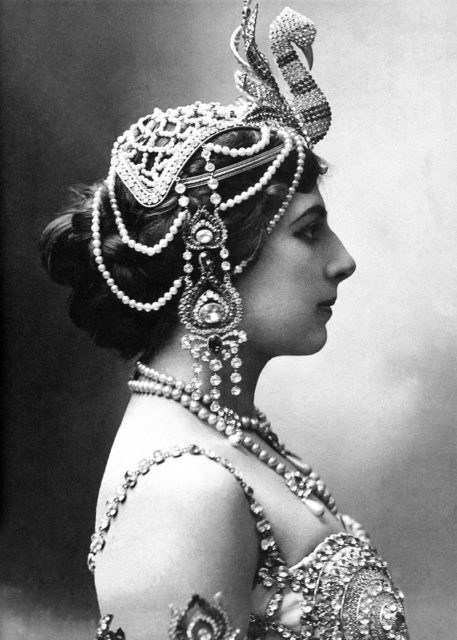

She was adept at using her talent to enchant her audiences, and she invented a new persona of Mata Hari, a Hindu princess who had been involved in the sacred Hindu method of dance since she was a child. She soon became friendly with millionaire Émile Étienne Guimet, the owner of the Musée Guimet, where she had made her dancing debut in 1905. She posed for photographs, either nearly naked or in her stage body stocking that made her appear nude. She tended to wear an East Asian style of jewelry, especially her signature headpieces and jeweled bras.

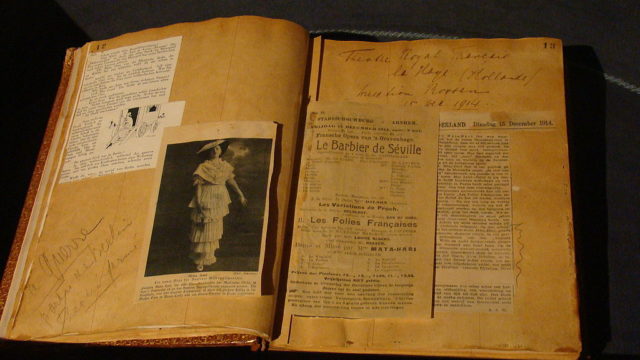

Her style of dance was currently all the rage in Paris. She helped to make exotic dancing more respectable due to her acceptance in wealthy social circles and her free-willed attitude. She had publicized affairs with military officers and high-ranking politicians, allowing her to cross international borders freely. Her lifestyle served to strengthen her image on stage until the approach of World War I. Suddenly, in the seriousness of the times, the public grew tired of her promiscuity and began to see her as a threat to security. She was still completing engagements across Europe, but due to public disapproval and her ageing body, she was last seen on stage in 1915.

Margaretha soon became involved with Captain Vadim Maslov, a Russian pilot serving in the French Army. When Maslov was shot down, she obtained permission from France’s external military intelligence agency, the Deuxième Bureau, to visit him on the condition of becoming a spy. Her dancing appearances for the Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany led the French Captain Georges Ladoux to believe she could obtain valuable military secrets by seduction. Unknown to the French, the Crown Prince was no more than a spoiled playboy who had little knowledge of military affairs.

Margaretha made arrangements to meet with the Crown Prince by offering to share French intelligence with the Germans. When General Walter Nicolai, the chief intelligence officer of the German Army, realized she had no more than gossip to offer, he accused her of being a spy.

In 1917, Margaretha was arrested in Paris, allegedly with a German check for a substantial amount found on her person, and put on trial. She was accused of spying for the Germans and was blamed for the deaths of fifty thousand soldiers. She maintained her innocence, claiming it was her work that took her to other countries; not activities for the German government. Margaretha’s Mata Hari persona was exposed as false, which further served to implicate her as being dishonest. Maslov abandoned her, refusing to testify on her behalf.

Recently, British historian Julie Wheelwright stated, “She really did not pass on anything that you couldn’t find in the local newspapers in Spain. [Margaretha] was an independent woman, a divorcee, a citizen of a neutral country, a courtesan and a dancer, which made her a perfect scapegoat for the French, who were then losing the war. She was kind of held up as an example of what might happen if your morals were too loose.”

At the age of 41, after blowing kisses to her executioners and refusing a blindfold, Margaretha Zelle was shot multiple times by a firing squad on October 15, 1917. She was then shot in the head by an officer who wanted to make sure she was dead. Her body was donated to the Museum of Anatomy in Paris when no family members claimed it; since then it seems to have disappeared.

Read another story from us: 102-Year-Old dancer sees herself on film for the first time

Through the years Hollywood, theater, and modern authors have elevated her Mata Hari persona as a cunning femme fatale – perhaps a skewed and unfair portrayal far beyond the reality of who she actually was. The sealed documents from Margaretha’s trial are scheduled to be released in October of 2017 by the French, and the truth about this most famous female spy may finally be revealed to the world.