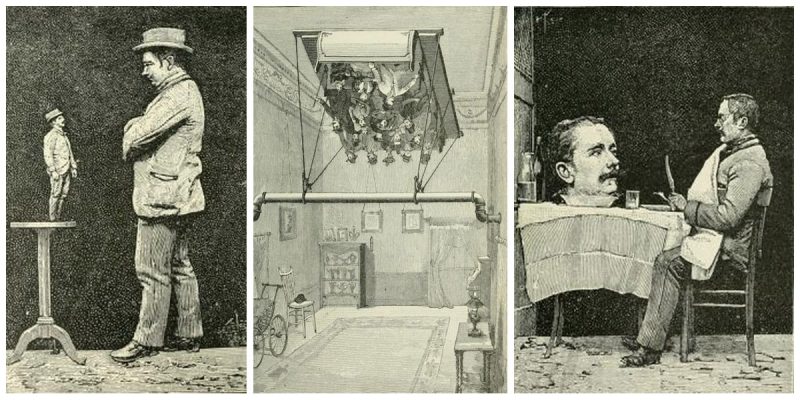

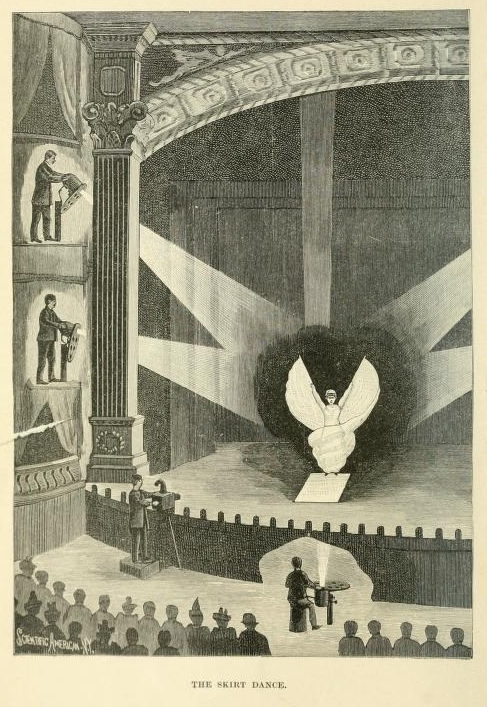

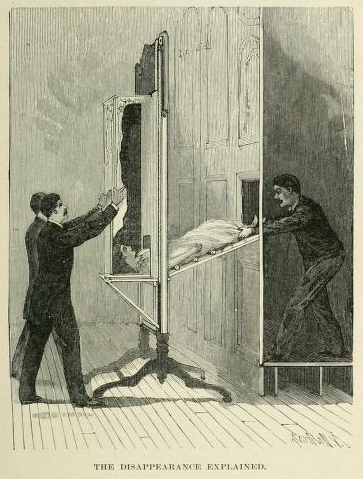

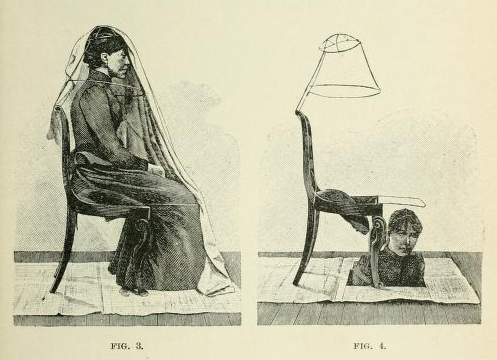

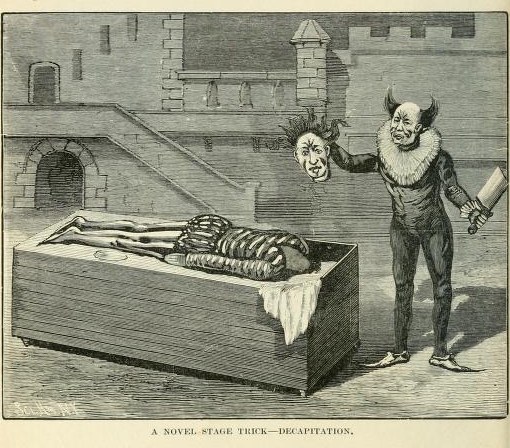

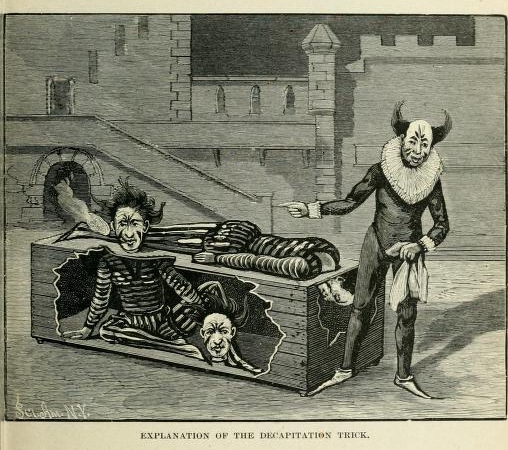

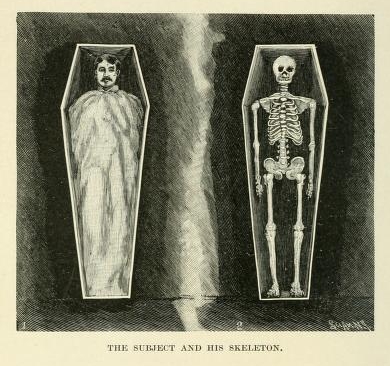

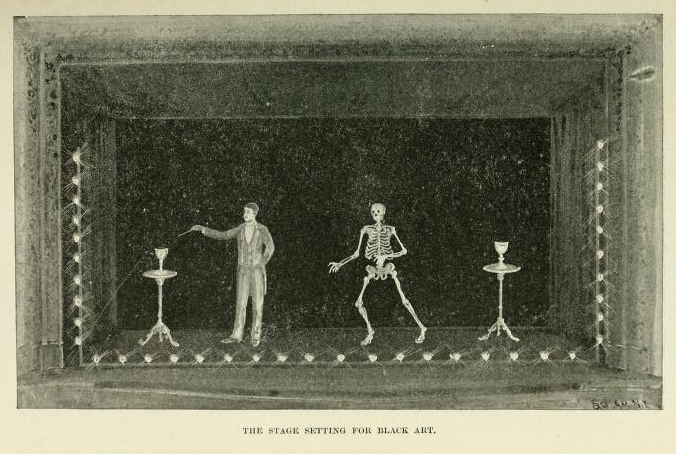

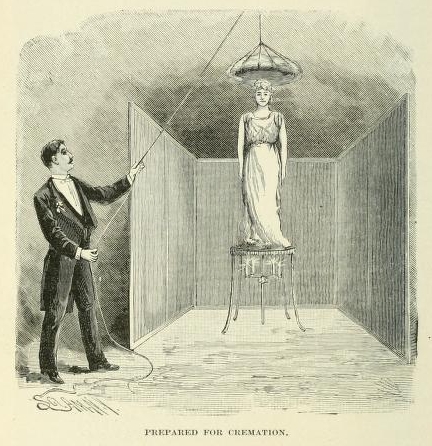

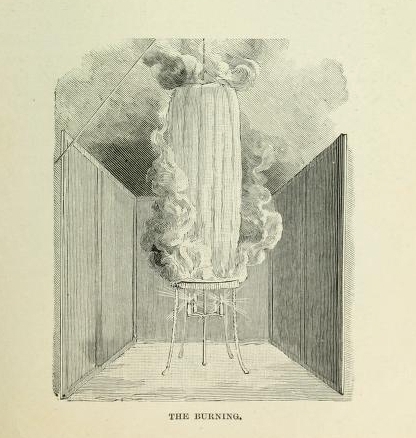

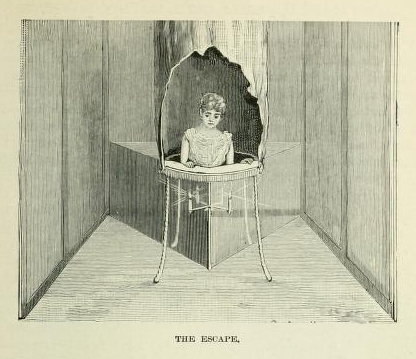

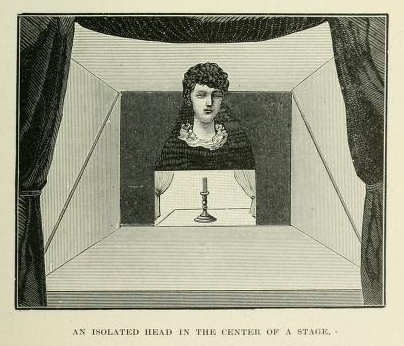

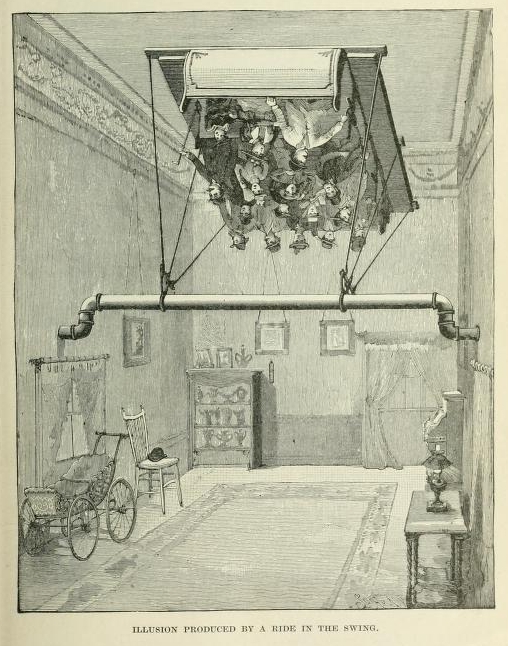

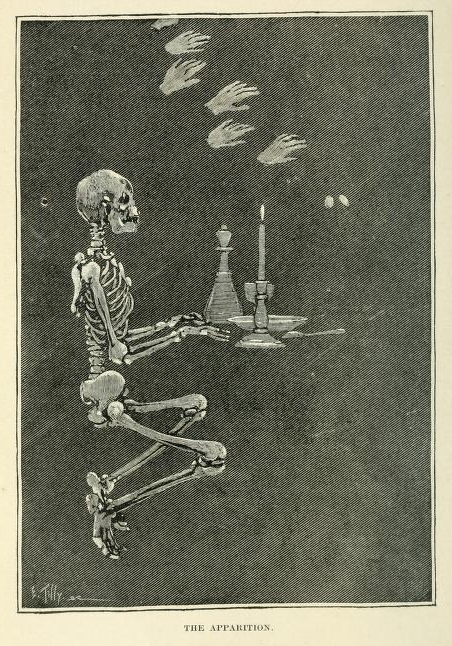

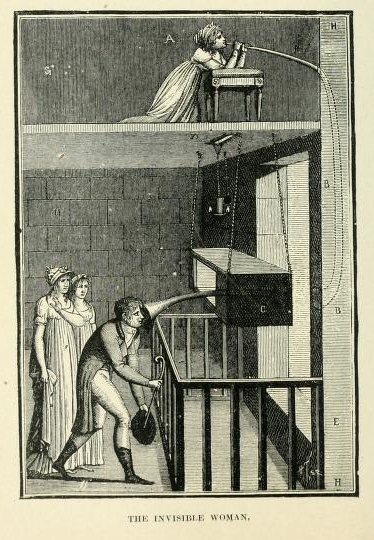

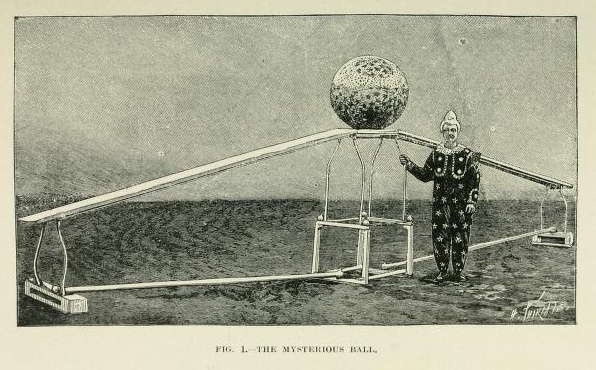

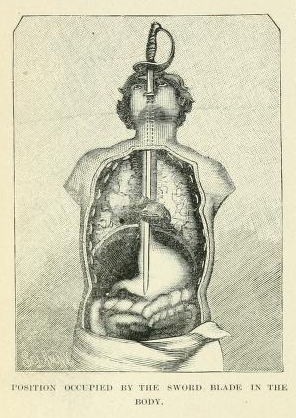

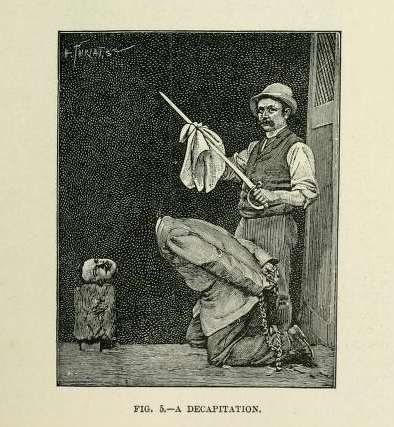

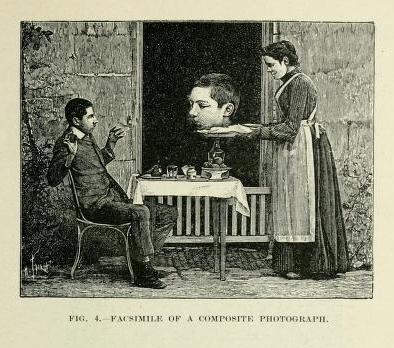

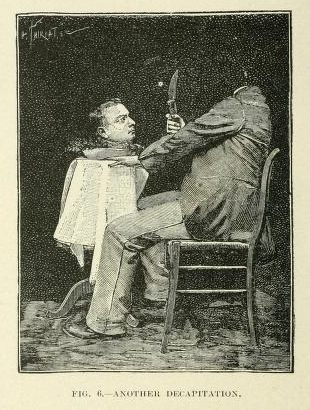

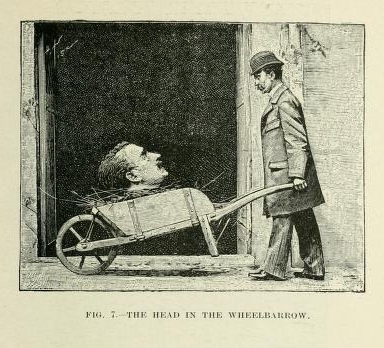

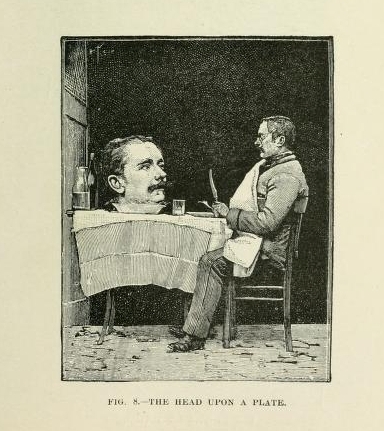

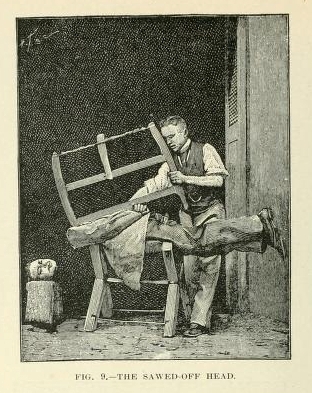

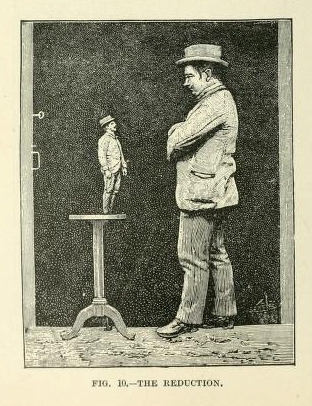

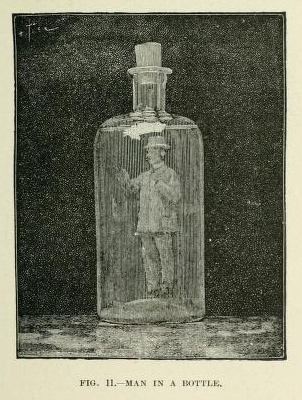

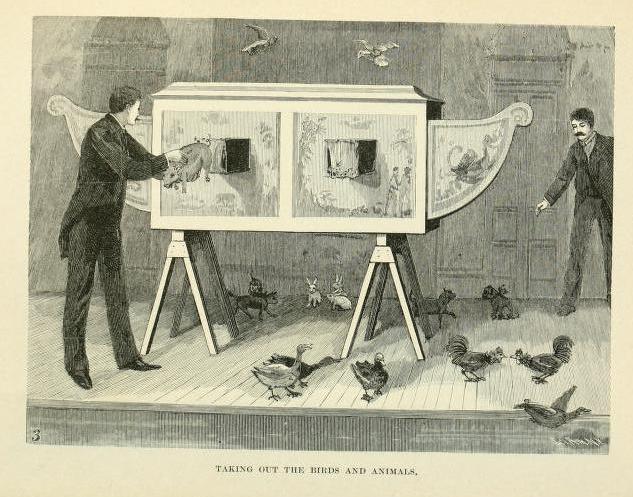

Selected images from a massive late 19th-century tome entitled Simply Magic, subtitled Stage Illusions and Scientific Diversions, including Trick Photography, compiled and edited by Albert A. Hopkins (1869 – 1939). The book takes a thorough tour through the popular magic tricks and illusions of the day, including along the way many delightfully surreal diagrams and illustrations, the top pick of which we’ve included here – often especially great when seen out of context. Towards the end are some particularly great “decapitation” trick photographs.

Magic, Stage Illusions And Scientific Diversions: Including Trick Photography is divided into five “books”: The Mysteries of Modern Magic, Conjurers’ Tricks and Stage Illusions, Ancient Magic, Science in the Theater, Automata, and Curious Toys, and Photographic Diversions.

During the 1890’s, Scientific American magazine published elaborate explanations of magic illusions. For several years, the identity of Scientific American’s “spy” remained a mystery to other magicians. But soon William Robinson’s name was slowly linked to the magazine. Harry Kellar was particularly upset to find descriptions of some of his most popular illusions, including the rope tie that formed the basis of his Spirit Cabinet routine that Robinson’s wife, Dot, operated in the Kellar show.

At the end of 1897, the publisher of Scientific American, collected the tricks under one cover, with additional material, including descriptions of theatrical special effects. It has an introduction by Henry Ridgely Evans and William Robinson along with H. J. Burlingame were thanked for their contributions.

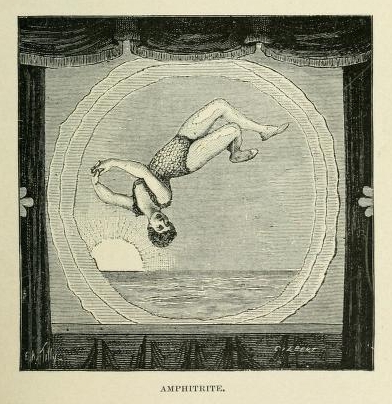

A few of the topics were “Conjurers Tricks and Stage Illusions”, “Jugglers and Acrobats”, “Fire Eaters and Sword Tricks”, “Ventriloquism”, “Shadowgraphy”, “Mental Magic”, “Temple Tricks of the Greeks”, “Stage Effects”, “Theater Secrets” and “Automata”.

Automata are mechanical figures which perform tasks that imitate a living person. Real automata have complex movements that are able to do many actions after being wound. Many were not made as children’s toys but were meant to be played by adults.

The period 1860 to 1910 is known as “The Golden Age of Automata”. During this period, many small family based companies of Automata makers thrived in Paris. They exported thousands of clockwork automata and mechanical singing birds around the world. It is these French automata that are collected today, although now rare and expensive they attract collectors worldwide. The main French makers were Vichy, Roullet & Decamps, Lambert, Phalibois, Renou and Bontems.

Magicians, over the years, have demonstrated both real and fake ones (using a hidden assistant).

Photos: California Digital Library