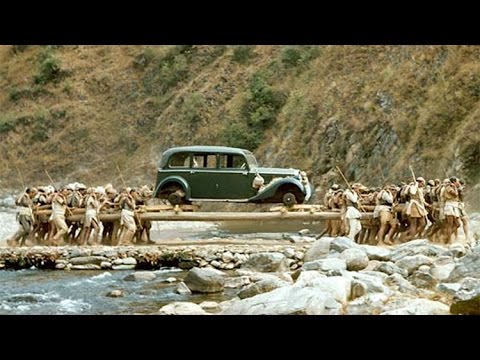

Recently, we stumbled upon an odd and fascinating photo of Nepali men carrying a German-made Mercedes on a rocky, hilly trail, and we decided to dig in deeper. This is what we’ve found.

In the 1940’s, Adolf Hitler presented the King Truibhuvan of Nepal, with a 1938 – Model Mercedes-Benz, and that was the first car even seen in Nepal.

Before this Himalayan nation had built its first serpentine Tribhuvan Highway in 1956, there were no modern roads in Nepal, except in the capital, so the workers were supposed to carry the car on the rocky, hilly trail to Kathmandu.

The use of humans to transport cargo dates to the ancient world, prior to domesticating animals and development of the wheel. Historically it remained prevalent in areas where slavery was permitted, and exists today where modern forms of mechanical conveyance are rare or impractical, or where it is impractical or impossible for mechanized transport to be used, such as in mountainous terrain, or thick jungle or forest cover.

Over time slavery diminished and technology advanced, but the role of porters for specialized transporting services remains strong in the 21st century. Examples include bellhops at hotels, red-caps at railway stations, skycaps at airports, and native bearers on adventure trips engaged by foreign travelers.

Porters, frequently called Sherpas in the Himalayas (after the ethnic group most Himalayan porters come from), are also an essential part of mountaineering: they are typically highly skilled professionals who specialize in the logistics aspect of mountain climbing, not merely people paid to carry loads (although carrying is integral to the profession). Frequently, porters/Sherpas work for companies who hire them out to climbing groups, to serve both as porters and as mountain guides; the term “guide” is often used interchangeably with “Sherpa” or “porter”, but there are certain differences. Porters are expected to prepare the route before and/or while the main expedition climbs, climbing up beforehand with tents, food, water, and equipment (enough for themselves and for the main expedition), which they place in carefully located deposits on the mountain. This preparation can take months of work before the main expedition starts. Doing this involves numerous trips up and down the mountain until the last and smallest supply deposit is planted shortly below the peak. When the route is prepared, either entirely or in stages ahead of the expedition, the main body follows. The last stage is often done without the porters, they remain at the last camp, a quarter mile or below the summit, meaning only the main expedition is given the credit for mounting the summit. In many cases, since the porters are going ahead, they are forced to free climb, driving spikes and laying safety lines for the main expedition to use as they follow. Porters (such as Sherpas for example), are frequently local ethnic people, well adapted to living in the rarified atmosphere and accustomed to living in the mountains. Although they receive little glory, porters or Sherpas are often considered among the most skilled of mountaineers and are generally treated with respect, since the success of the entire expedition is only possible through their work.