The roller ship, or roller steamer, was an unconventional – and unsuccessful – ship design of the late nineteenth century, which attempted to propel itself by means of large wheels. Only one such vessel was constructed and it was called the Ernest Bazin, after its inventor.

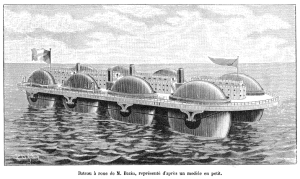

The principle behind the design was similar to that of the slightly later hydrofoil; by avoiding as much hull contact with the water as possible, the amount of drag could be reduced and – in theory – the vessel could be made to move much faster for a given amount of power. As envisaged by Bazin, the main hull was lifted out of the water, with large hollow discs attached to each side. These discs would provide the buoyancy of the ship, as well as part of its propulsive power. These wheels were independently driven, with a separate screw lowered into the water from the hull to propel the boat.

The discs were lenticular: they tapered to a point, like the hulls of ships. Indeed, when pushed forwards through the water, without any rotational movement, they behaved exactly like a conventional hull. When rotated, however, they proved in testing to be much more efficient, due to the propulsive force being expended both vertically and horizontally. It was found that the overall speed ought to be roughly two-thirds the speed of rotation of the wheels.

An early attempt to produce such a ship was made in the early 1880s by Robert Fryer, who built the Alice at a cost of some £14,000 after twelve years of experimentation. It consisted of three paddle wheels in a rough triangular layout, with a flat deck mounted above them; there was apparently no other propulsion. The project was a complete failure, perhaps due to the lack of any propulsion other than the paddles.

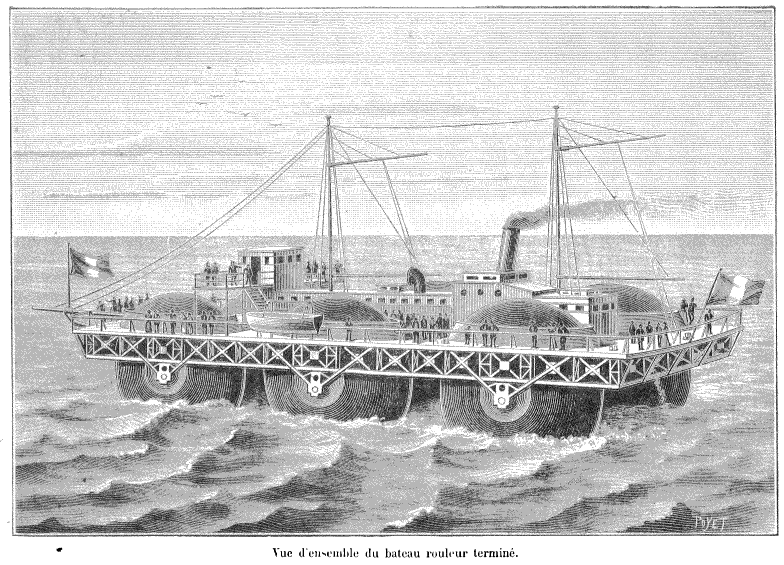

The first and only operational roller ship, the 280-ton Ernest-Bazin, was designed by the French inventor Ernest Bazin after five years of model-based tests and launched at Saint-Denis on August 19, 1896. It had three pairs of discs ten-metres in diameter and three-metres thick; each pair was independently driven by a fifty-horsepower engine and, under normal conditions, about one-third submerged. The main hull was supported just above the axes of these discs, 4m above the sea level, and was about 40 by 12 metres; it contained the engines as well as the crew housing.

Bazin predicted the ship would be able to make about eighteen knots, perhaps pushing twenty at full power, but hoped that a ship of similar build with the power that could propel a convention ship to 20 knots could achieve speeds of 47 knots; many observers estimated, however, that the design was theoretically capable of thirty-two knots based on the size and power of the wheels and on early model tests. This compared very favourably with contemporary steamships; the fast ocean liners of the day could manage slightly over twenty knots, whilst high-powered military Torpedo boat destroyers could break thirty. The fuel consumption was also anticipated to be sharply reduced; a full-scale vessel was predicted by Bazin to consume only 800 tons of coal for a thirty-knot Atlantic crossing, compared to 3000–4000 tons for a 22-knot crossing by a conventional liner.

The Ernest-Bazin was a test ship, meant to test the design. If its test succeeded, a roller ship with 4 disc pairs was to be constructed to transport passengers from Le Havre to New York City. The roller ship proved it’s seaworthiness in march 1897 in Rouen, a month later in the port of Le Havre and when it crossed the English Channel in the direction for England. During the time following this, it navigated along the east coast of England, entered several ports and caLled forth a lot of excitement everywhere. But the tests remained unsatisfying. The ship turned out to be unstable, it was undermotorised. The ship propeller was dimensioned too small. The wheels slowed down the ship instead of pulling it forwards because the resistance of the water churned up by the wheels was too big. Result: Even though Bazin had calculated on a minimal speed of 30 knots, the ship never made more than seven. The brothers Bazin’s imagination of a functional, fast and economical “roller ship” should remain an unfulfilled dream. The boat’s construction was too deficient to revolutionise naval architecture.

In 1897, Frederick Knapp, a lawyer in Prescott, Ontario, designed another type of vessel which he termed a “roller boat”; this was essentially a single long cylinder which sat in the water. An engine inside, supported on rotating bearings, caused the outer surface of the cylinder to rotate, acting as a paddle wheel. However, it suffered much the same flaws as Bazin’s design; the hypothetical “mile a minute” was, in practice, no more than five knots, and the vessel proved difficult to control. In 1927 that area of the harbour was being redeveloped and the hull of the old ROLLER BOAT was dug out and cut up for scrap.