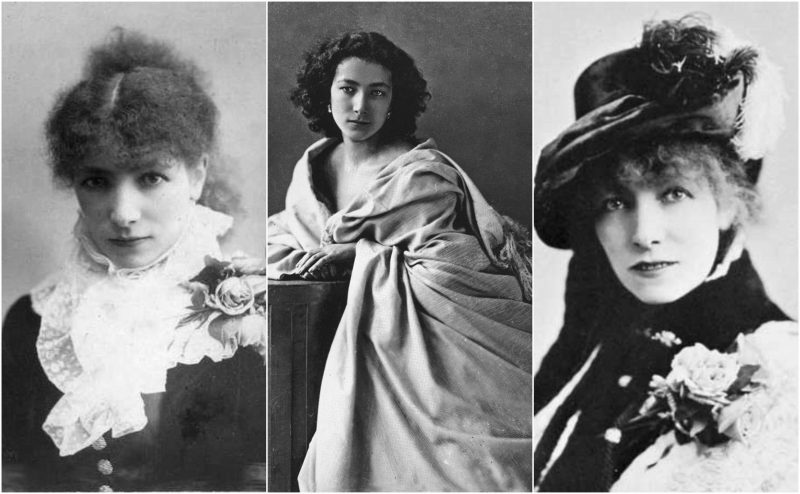

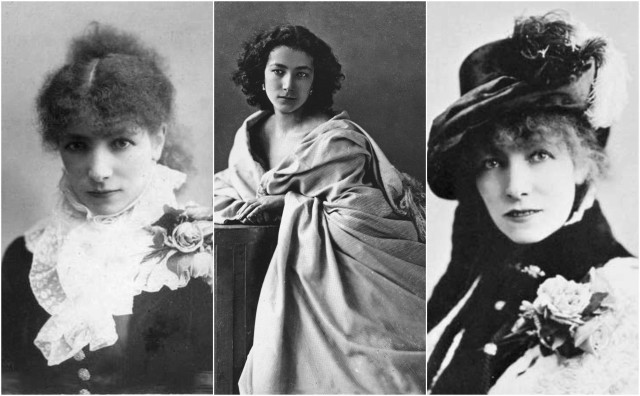

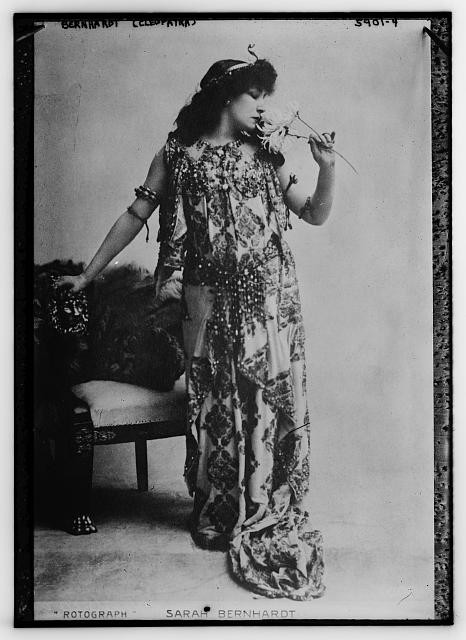

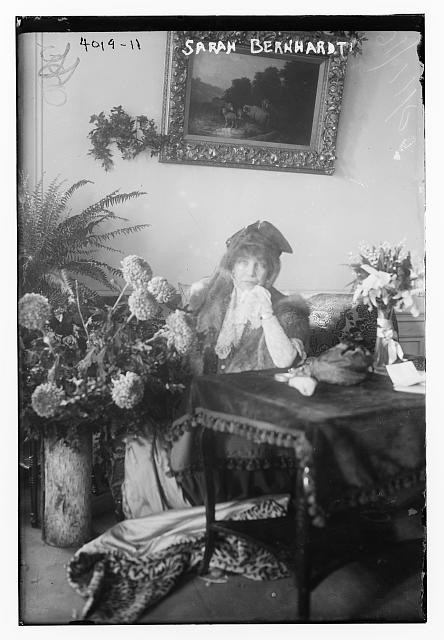

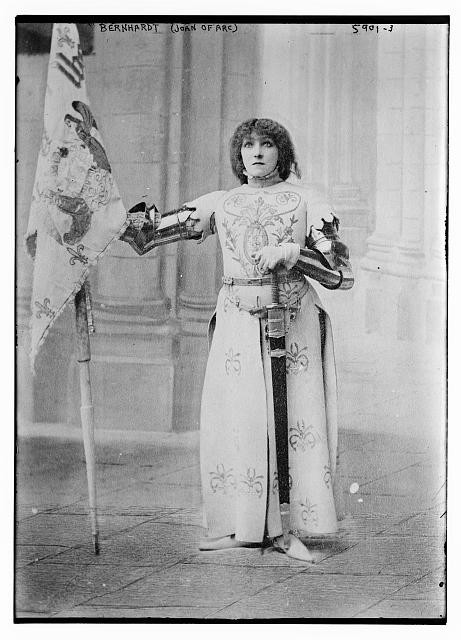

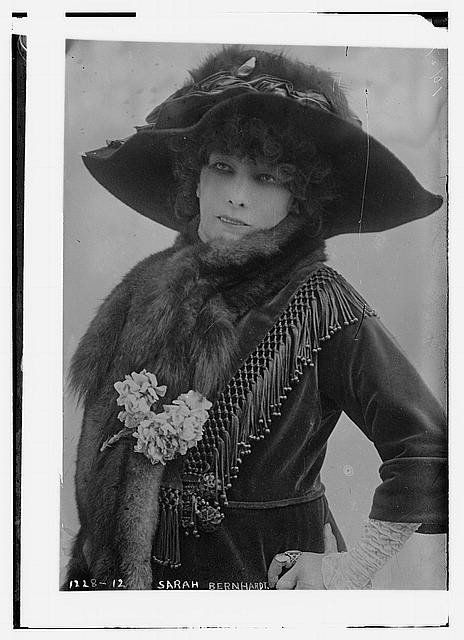

Referred to as “the most famous actress the world has ever known”, and is regarded as one of the finest actors of all time, Sarah Bernhardt made her fame on the stages of France in the 1870’s, at the beginning of the Belle Epoque period, and was soon in demand in Europe and the Americas. She developed a reputation as a sublime dramatic actress and tragedienne, earning the nickname “The Divine Sarah”. In her later career, she starred in some of the earliest films ever produced.

Bernhardt’s stage career started in 1862 while she was a student at the Comédie-Française, France’s most prestigious theater. She decided to leave France and soon ended up in Belgium, where she became the mistress of Henri, Prince de Ligne, and gave birth to their son, Maurice, in 1864. After Maurice’s birth, the Prince proposed marriage, but his family forbade it and persuaded Bernhardt to refuse and end their relationship.

After being expelled from the Comédie Française, she resumed the life of courtesan to which her mother had introduced her at a young age, and made considerable money during that period (1862–65). During this time she acquired her famous coffin, in which she often slept in lieu of a bed – claiming that doing so helped her understand her many tragic roles.

She made her fame on the stages of Europe in the 1870’s and was soon in demand all over Europe. Her first tour of the United States and Canada took place in 1880-81 (157 performances in 31 cities). In 1887, she toured South America including Cuba where she performed in the Sauto Theater, in Matanzas. In 1888, she toured Italy, Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. In 1891-92, she took part in a worldwide tour which included much of Europe, Russia, North & South America, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Samoa. Another tour of America took place in 1896. 1901 saw her 6th American Tour, 1906 her 7th (her “first Farewell Tour” where she concluded the Southern California leg with “La Tosca” at the Venice Auditorium), 1910 her 8th (when she made a recording on Wax Cylinder at Thomas Edison’s laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey), and 1913-1914 her 9th (on the evening of March 12th, 1913, in Los Angeles, she was involved in a motorcar accident while she was being driven in a taxi to the downtown Orpheum Theatre to appear in “La Tosca”).

After establishing herself on the stage, by age 25 Bernhardt began to study painting and sculpture under Mathieu Meusnier and Emilio Franceschi. Her early work consisted mainly of bust portraiture, but later works were more ambitious in design. Fifty works have been documented, of which 25 are known to still exist, including the naturalistic marble Après la Tempête (National Museum of Women in the Arts). Her work was exhibited at the Salon 1874 – 1886, with several items shown during the Columbia Exposition in Chicago and at the 1900 Exposition Universelle. Bernhardt also painted, and while on a theatrical tour to New York, hosted a private viewing of her paintings and sculpture for 500 guests. She may be best known for her 1880 Art Nouveau decorative bronze inkwell, which portrays a self-portrait with bat wings and a fish tail (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). This may have been inspired by her 1874 performance in Le Sphinx

Bernhardt was one of the pioneer silent movie actresses, debuting as Hamlet in the two-minute long film Le Duel d’Hamlet in 1900. (Technically, this was not a silent film, and in fact, it is cited as one of the first examples of a sound and moving image syncing system created with the new phono-cinema-theatre system). She went on to star in eight motion pictures and two biographical films in all. The latter included Sarah Bernhardt à Belle-Isle (1912), a film about her daily life at home.

In 1905, while performing in Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca in Teatro Lírico do Rio de Janeiro, Bernhardt injured her right knee when jumping off the parapet in the final scene. The leg never healed properly. By 1915, gangrene set in and her entire right leg was amputated; she was required to use a wheelchair for several months. Bernhardt reportedly refused a $10,000 offer by a showman to display her amputated leg as a medical curiosity. (While P.T. Barnum is usually cited as the one to have made the offer, he had been dead since 1891.)

She continued her career, sometimes without using a wooden prosthetic limb, which she did not like. She carried out a successful tour of America in 1915, and on returning to France she played in her own productions almost continuously until her death. Later successes included Daniel (1920), La Gloire (1921), and Régine Armand (1922). According to Arthur Croxton, the manager of London’s Coliseum, the amputation was not apparent during her performances, which were done with the use of the artificial limb.

Her physical condition may have limited her mobility on the stage, but the charm of her voice, which had altered little with age, ensured her triumphs.