Spending the night or the weekend in a stump house may sound like an outdoors adventure or a camping holiday, but in the 1800s, when settlers headed by the thousands to the Pacific Northwest, they were forced to improvise with such dwellings, living in them until they were able to build a more conventional home.

The arrival of the settlers into this part of the North American continent was followed by numerous of challenges. After their arduous journey across mountains, valleys, rivers, making it to the Pacific Northwest meant they needed to find proper resources to build a house as well as to find a way to eat. So growing crops and taking care of livestock were priorities.

Many settlers were ingenious from the start. Finding the stumps of gigantic trees that had been felled by logging companies still rooted in the ground, they saw an opportunity too good to pass up. The loggers had opened up what was previously dense forest, but the pioneers still faced the long and arduous task of clearing these tree stumps before farming could begin. While this hard work was in progress, some of the stumps were put to various uses. For example, one might be leveled off and used as a stage for music and dancing. Then there was adapting the huge tree stumps to be a shelter, and even though it was a temporary solution, it was a brilliant one.

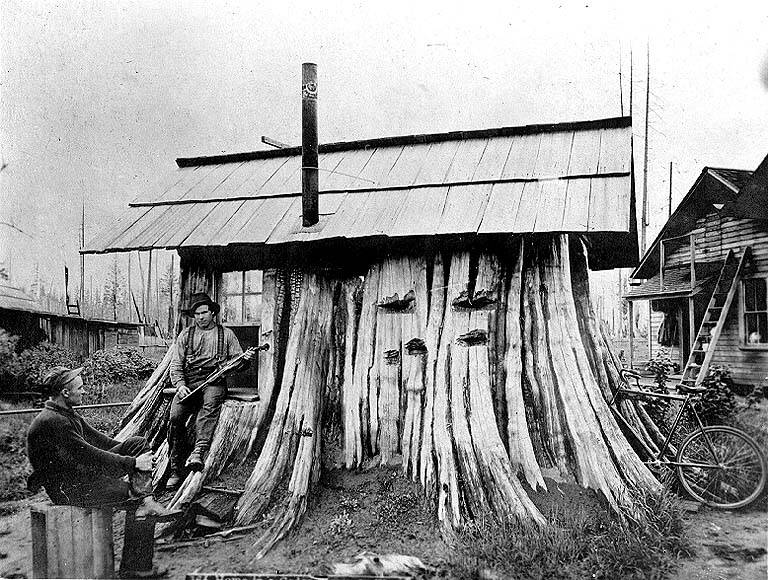

Building a stump dwelling still took a tremendous amount of effort. Obviously, not every stump would make a good home. Many were too damaged or burned. But, with limited resources, the new arrivals were creative in making the best use of what was there. First, the interior had to hollowed out, leaving a good thick wall. Putting a solid roof on the stump took careful work and patience, as did cutting doors and windows and installing a stovepipe. Some stump houses had two or even three stories and were equipped with everything a family home needed, with space to cook, sleep, and store their belongings.

Winter was probably the scariest period to spend in a stump house because severe weather hits the North Pacific during those months, with super low temperatures and snow sometimes persisting for days and months.

So they were perhaps not the perfect houses, but they look somewhat magical today, as if they were the creation of forest elves. It was not unusual for people to turn their trusty stump dwelling to another purpose, such as housing livestock, after they had moved out to a conventional home.

One man, William McDonald, even used a large abandoned stump structure as a U.S. Postal Office. His main office was in a far-off area of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, roughly 10 miles from Port Angeles.

Some of these remarkable tree-stump transformations have been well documented. Perhaps the best known belonged to the Lennstroms, a migrant family originally from Sweden. The couple, Gustav Erik Lennstrom and Brita Charlotta, had three children, and they were also joined in Edgecomb, Washington, by Brita’s brother Johan Axel Westerlund.

It is known that Westerlund was skilled in wood crafting, having experience as a cabinet-maker back in Sweden. For building the stump house, he hollowed out a particularly sizable cedar-tree stump, while Gustav finished the house by placing a door, window, and roof on it. The family also installed a wood stove inside the stump house to keep it warm during cold days. After months living in it, the family built a regular home, but Westerland reportedly continued to occupy the stump house because he liked it so much.

The Edgecomb stump house became known as a regional icon thanks to Darius Kinsey, the photographer who immortalized the Lennstroms’ house in eight photographs in 1901 and who, in the following two decades, marketed the photos both as postcards and also stereoview cards. Kinsey supposedly adored the stump house so much that in 1902 he used a tiny image of it in the stationery of his business.