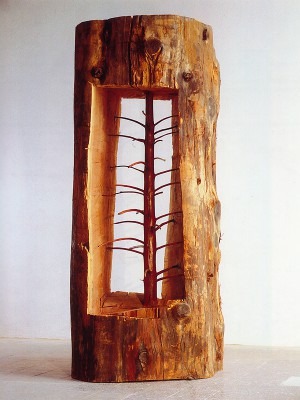

Inspired by the quiet slowness of growth in the natural world, the artist asks us to take a moment to stop and think about the concept of time and how there’s a common vital force in all living things. Art Gallery of Ontario website

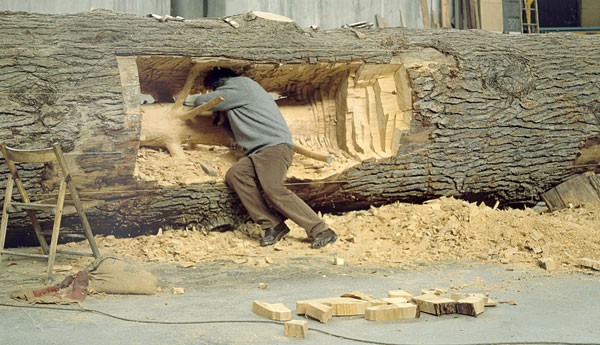

The Hidden Life Within was displayed at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2012. Would have been great to see in person.

.

.

.

Growth rings, also referred to as tree rings or annual rings, can be seen in a horizontal cross section cut through the trunk of a tree.

Growth rings are the result of new growth in the vascular cambium, a layer of cells near the bark that is classified as a lateral meristem; this growth in diameter is known as secondary growth.

Visible rings result from the change in growth speed through the seasons of the year; thus, critical for the title method, one ring generally marks the passage of one year in the life of the tree.

The rings are more visible in temperate zones, where the seasons differ more markedly.

The inner portion of a growth ring is formed early in the growing season, when growth is comparatively rapid (hence the wood is less dense) and is known as “early wood” (or “spring wood”, or “late-spring wood”).

The outer portion is the “late wood” (and has sometimes been termed “summer wood”, often being produced in the summer, though sometimes in the autumn) and is denser.

Many trees in temperate zones make one growth ring each year, with the newest adjacent to the bark. Hence, for these, for the entire period of a tree’s life, a year-by-year record or ring pattern is formed that reflects the age of the tree and the climatic conditions in which the tree grew.

Adequate moisture and a long growing season result in a wide ring, while a drought year may result in a very narrow one.

Direct reading of tree ring chronologies is a learned science, for several reasons. First, contrary to the single ring per year paradigm, alternating poor and favorable conditions, such as mid-summer droughts, can result in several rings forming in a given year.

In addition, particular tree species may present “missing rings”, and this influences the selection of trees for study of long time spans. For instance, missing rings are rare in oak and elm trees.

Critical to the science, trees from the same region tend to develop the same patterns of ring widths for a given period of historical study.

These patterns can be compared and matched ring for ring with trees growing at the same time, in the same geographical zone (and therefore under similar climatic conditions). When these tree-ring patterns are carried back, from tree to tree in the same locale, in overlapping fashion, chronologies can be built up—both for entire geographical regions and sub-regions.

Moreover, wood from ancient structures with known chronologies can be matched to the tree ring data (a technique called cross-dating), and the age of the wood can thereby be determined precisely. Cross-dating was originally done by visual inspection; computers have been harnessed to do the task, applying statistical techniques to assess the matching.