Built for the super rich of 1800s, the sporting club, catered to a very wealthy clientele from nearby Pittsburgh. Some of the big names included Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick. Lake Conemaugh was held back by the South Fork Dam, a large earth-fill dam that was completed by the club in 1881. By 1889, the dam was in dire need of repairs.

The New York Times:

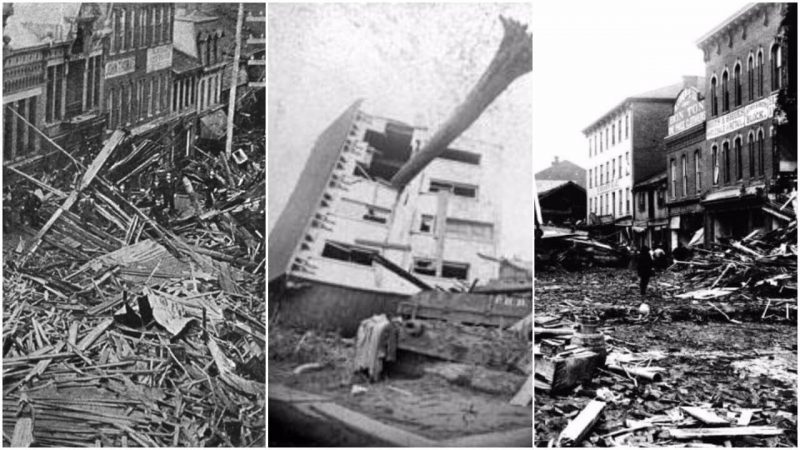

A lake on the neighboring hills bursts its barriers and sweeps everything before it – men, women and children swallowed up by angry flood – awful scenes witnessed by survivors

Pittsburg, May 31 – An appalling catastrophe is reported from Johnstown, Cambria County, the meagre details of which indicate that that city of 25,000 inhabitants has been practically wiped out of existence and that hundreds if not thousands of lives have been lost.

A dam at the foot of a mountain lake eight miles long and three miles wide, about nine miles up the valley of the South Fork of the Conemaugh River, broke at 4 o’clock this afternoon, just as it was struck by a waterspout, and the whole tremendous volume of water swept in a resistless avalanche down the mountain side, making its own channel until it reached the South Fork of the Conemaugh, swelling it to the proportions of Niagara’s rapids.

The flood swept onward to the Conemaugh like a tidal wave, over twenty feet in height, to Johnstown, six or eight miles below, gathering force as it tore along through the wider channel, and quickly swept everything before it. Houses, factories and bridges were overwhelmed in the twinkling of an eye and with their human occupants were carried in a vast chaos down the raging torrent.

High above the city, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania built the South Fork Dam between 1838 and 1853, as part of a cross-state canal system, the Main Line of Public Works. Johnstown was the eastern terminus of the Western Division Canal, supplied with water by Lake Conemaugh, the reservoir behind the dam. As railroads superseded canal barge transport, the Commonwealth abandoned the canal and sold it to the Pennsylvania Railroad. The dam and lake were part of the purchase, and the railroad sold them to private interests.

Henry Clay Frick led a group of speculators, including Benjamin Ruff, from Pittsburgh to purchase the abandoned reservoir, modify it, and convert it into a private resort lake for their wealthy associates. Many were connected through business and social links to Carnegie Steel. Development included lowering the dam to make its top wide enough to hold a road, and putting a fish screen in the spillway (the screen also trapped debris). These alterations are thought to have increased the vulnerability of the dam. Moreover, a system of relief pipes and valves, a feature of the original dam, previously sold off for scrap, was not replaced, so the club had no way of lowering the water level in the lake in case of an emergency. The members built cottages and a clubhouse to create the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, an exclusive and private mountain retreat. Membership grew to include more than 50 wealthy Pittsburgh steel, coal, and railroad industrialists.

Lake Conemaugh at the club’s site was 450 feet in elevation above Johnstown. The lake was about 2 miles long, about 1 mile wide, and 60 feet deep near the dam. The lake had a perimeter of 7 miles and held 20 million tons of water.

The dam was 72 feet high and 931 feet long. After 1881, when the club opened, the dam frequently sprang leaks. It was patched, mostly with mud and straw. Additionally, a previous owner had removed and sold for scrap the three cast iron discharge pipes that had allowed a controlled release of water. There had been some speculation as to the dam’s integrity, and concerns had been raised by the head of the Cambria Iron Works downstream in Johnstown.

On May 28, 1889, a storm formed over Nebraska and Kansas and headed east. When the storm struck the Johnstown-South Fork area two days later, it was the worst downpour that had ever been recorded in that part of the country. The U.S. Army Signal Corps estimated that 6 to 10 inches of rain fell in 24 hours.r the region. The river that ran through Johnstown was about to overwhelm its banks.

Elias Unger, president of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, awoke to the sight of Lake Conemaugh swollen after a night-long heavy rainfall. Unger ran outside in the still-pouring rain to assess the situation and saw that the water was nearly cresting the dam. He quickly assembled a group of men to save the face of the dam by trying to unclog the spillway; it was blocked by the broken fish trap and debris caused by the swollen waterline. Other men tried digging another spillway at the other end of the dam to relieve the pressure, without success. Most remained on top of the dam, some plowing earth to raise it, while others tried to pile mud and rock on the face to save the eroding wall.

At around 3:10 p.m., the South Fork Dam collapsed, freeing the 20 million tons of Lake Conemaugh to cascade down the Little Conemaugh River. It took about 40 minutes for the entire lake to drain of the water. The first town to be hit by the flood was South Fork. The town was on high ground, and most of the people escaped by running up the nearby hills when they saw the dam spill over. Some 20 to 30 houses were destroyed or washed away, and four people were killed.

On its way downstream toward Johnstown, 14 miles away, the crest picked up debris, such as trees, houses, and animals. At the Conemaugh Viaduct, a 78-foot high railroad bridge, the flood temporarily was stopped when debris jammed against the stone bridge’s arch. But within seven minutes, the viaduct collapsed, allowing the flood to resume its course. Because of this, the surging river gained renewed hydraulic head, resulting in a stronger wave hitting Johnstown than otherwise would have been expected. The small town of Mineral Point, one mile below the Conemaugh Viaduct, was hit with this renewed force. About 30 families lived on the village’s single street. After the flood, only bare rock remained.

The village of East Conemaugh was next. One witness on high ground near the town described the water as almost obscured by debris, resembling “a huge hill rolling over and over”. From his locomotive, the engineer John Hess heard the rumbling of the approaching flood. Throwing his locomotive into reverse, Hess raced backward toward East Conemaugh, the whistle blowing constantly. His warning saved many people who reached high ground. When the flood hit, it picked up the locomotive and tossed it aside; Hess himself survived, but at least 50 people died, including about 25 passengers stranded on trains in the town.

Before hitting the main part of Johnstown, the flood surge hit the Cambria Iron Works at the town of Woodvale, sweeping up railroad cars and barbed wire in its moil. Of Woodvale’s 1,100 residents, 314 died in the flood. Boilers exploded when the flood hit the Gautier Wire Works, causing black smoke seen by the Johnstown residents. Miles of itsbarbed wire became entangled in the debris in the flood waters.

Some 57 minutes after the South Fork Dam collapsed, the flood hit Johnstown. The residents were caught by surprise as the wall of water and debris bore down, traveling at 40 miles per hour and reaching a height of 60 feet in places. Some, realizing the danger, tried to escape by running towards high ground but most people were hit by the surging floodwater. Many people were crushed by pieces of debris, and others became caught in barbed wire from the wire factory upstream. Those who reached attics, or managed to stay afloat on pieces of floating debris, waited hours for help to arrive.

At Johnstown, the Stone Bridge, which was a substantial arched structure, carried the Pennsylvania Railroad across the Conemaugh River. The debris carried by the flood formed a temporary dam at the bridge, resulting in the flood surge rolling upstream along the Stoney Creek River. Eventually, gravity caused the surge to return to the dam, causing a second wave to hit the city, but from a different direction. Some people who had been washed downstream became trapped in an inferno as the debris piled up against the Stone Bridge caught fire; at least 80 people died there. The fire at the Stone Bridge burned for three days. After floodwaters receded, the pile of debris at the bridge was seen to cover 30 acres, and reached 70 feet in height. It took workers three months to remove the mass of debris, largely because it was bound by the steel wire from the ironworks. Dynamite was eventually used to clear it. Still standing and in use as a railroad bridge, the Stone Bridge is a landmark associated with survival and recovery from the flood. In 2008, it was restored in a project including new lighting as part of commemorative activities related to the flood.

The total death toll was 2,209, making the disaster the largest loss of civilian life in the United States at the time (perhaps with exception of the Peshtigo Fire). It was later surpassed by fatalities in the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Some historians believe the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane and 1906 San Francisco earthquake killed more people in the U.S. than did the Johnstown Flood, but the official death toll was lower.

Ninety-nine entire families died in the flood, including 396 children. One hundred twenty-four women and 198 men were widowed, 98 children were orphaned. One-third of the dead, 777 people, were never identified; their remains were buried in the “Plot of the Unknown” in Grandview Cemetery in Westmont.

It was the worst flood to hit the U.S. in the 19th century. Sixteen hundred homes were destroyed, $17 million in property damage levied, and 4 square miles of downtown Johnstown were completely destroyed. Clean-up operations continued for years. Although Cambria Iron and Steel’s facilities were heavily damaged, they returned to full production within a year and a half.