The Hollywood Ten or the Hollywood Blacklist is one of those “from hero to zero” stories, or kind of a Cinderella watched from a reverse.

It was the mid-40s, and the world was just trying to forget the devastating and terrible war. Holywood-wise, it was a good era, it was the heyday of Humprey Bogart’s career, he made his most memorable films in this decade. Orson Wells made his groundbreaking Citizen Cane. Film Noir was in its heights, to sum up, it was a starstruck era.

So, Hollywood was practically packed with high-paid directors, screenwriters, actors; oscar worth scripts were flying around, and seemingly everyone was doing just fine.. except not everyone.

They were one of the highest-paid actors, directors, and screenwriters; their movies were selling, people loved what they did, studios as well (for obvious reasons), the academy loved them, so it all seemed like these folks had chosen the right profession, but there was one teeny-weeny little problem, they had chosen the wrong party: the communist party.

So, from Hollywood “sweethearts” they became known as “Red Fascists,” Traitors, Stalin Lovers; people didn’t love their movies anymore, studios were not as welcomed as they used to be, being nominated for an Oscar was basically a “fiction,”

The Hollywood blacklist was rooted in events of the 1930s and the early 1940s, encompassing the height of the Great Depression and World War II. Two major film industry strikes during the 1930s increased tensions between the Hollywood producers and the unions, particularly the Screen Writers Guild.

The American Communist Party lost substantial support after the Moscow show trials of 1936–38 and the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of 1939. The U.S. government began turning its attention to the possible links between Hollywood and the party during this period. Under then chairman Martin Dies, Jr., the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) released a report in 1938 claiming that communism was pervasive in Hollywood. Two years later, Dies privately took testimony from a former Communist Party member, John L. Leech, who named forty-two movie industry professionals as Communists. After Leech repeated his charges in supposed confidence to a Los Angeles grand jury, many of the names were reported in the press, including those of stars Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Katharine Hepburn, Melvyn Douglas and Fredric March, among other well-known Hollywood figures. Dies said he would “clear” all those who cooperated by meeting with him in what he called “executive session”. Within two weeks of the grand jury leak, all those on the list except for actress Jean Muir had met with the HUAC chairman. Dies “cleared” everyone except actor Lionel Stander, who was fired by the movie studio, Republic Pictures, where he was contracted.

In 1941, producer Walt Disney took out an ad in Variety, the industry trade magazine, declaring his conviction that “Communist agitation” was behind a cartoonists and animators’ strike. According to historians Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, “In actuality, the strike had resulted from Disney’s overbearing paternalism, high-handedness, and insensitivity.” Inspired by Disney, California State Senator Jack Tenney, chairman of the state legislature’s Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, launched an investigation of “Reds in movies”. The probe fell flat, and was mocked in several Variety headlines.

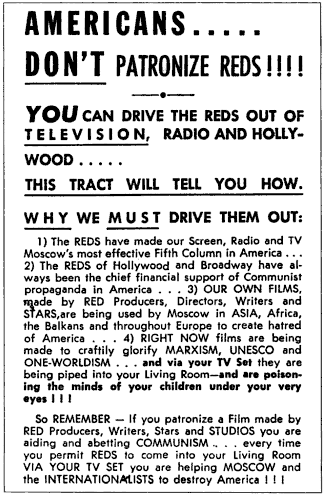

The subsequent wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union brought the American Communist Party newfound credibility. During the war, membership in the party reached a peak of 50,000.As World War II drew to a close, perceptions changed again, with communism increasingly becoming a focus of American fears and hatred. In 1945, Gerald L. K. Smith, founder of the neofascist America First Party, began giving speeches in Los Angeles assailing the “alien minded Russian Jews in Hollywood”. Mississippi congressman John E. Rankin, a member of HUAC, held a press conference to declare that “one of the most dangerous plots ever instigated for the overthrow of this Government has its headquarters in Hollywood … the greatest hotbed of subversive activities in the United States.” Rankin promised, “We’re on the trail of the tarantula now”. Reports of Soviet repression in Eastern and Central Europe in the war’s aftermath added more fuel to what became known as the “Second Red Scare”. The growth of conservative political influence and the Republican triumph in the 1946 Congressional elections, which saw the party take control of both theHouse and Senate, led to a major revival of institutional anticommunist activity, publicly spearheaded by HUAC. The following year, the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA), a political action group cofounded by Walt Disney, issued a pamphlet advising producers on the avoidance of “subtle communistic touches” in their films. Its counsel revolved around a list of ideological prohibitions, such as “Don’t smear the free-enterprise system … Don’t smear industrialists … Don’t smear wealth … Don’t smear the profit motive … Don’t deify the ‘common man’… Don’t glorify the collective”.

On July 29, 1946, William R. Wilkerson, publisher and founder of The Hollywood Reporter, published a “TradeView” column entitled “A Vote For Joe Stalin”. It named as Communist sympathizers Dalton Trumbo, Maurice Rapf, Lester Cole, Howard Koch, Harold Buchman, John Wexley, Ring Lardner Jr., Harold Salemson, Henry Meyers, Theodore Strauss, and John Howard Lawson. In August and September 1946, Wilkerson published other columns containing names of numerous purported Communists and sympathizers. They became known as “Billy’s List” and “Billy’s Blacklist. “In 2012, in a 65th anniversary article, Wilkerson’s son apologized for the newspaper’s role in the blacklist. He said that his father was motivated by revenge for his own thwarted ambition to own a studio.

In October 1947, drawing upon the list named in the Hollywood Reporter, the House Committee on Un-American Activities subpoenaed a number of persons working in the Hollywood film industry to testify at hearings. It had declared its intention to investigate whether Communist agents and sympathizers had been planting propaganda in U.S. films.

The hearings opened with appearances by Walt Disney and Ronald Reagan, then president of the Screen Actors Guild. Disney testified that the threat of Communists in the film industry was a serious one, and named specific people who had worked for him as probable Communists. Reagan testified that a small clique within his union was using “communist-like tactics” in attempting to steer union policy, but that he did not know if those (unnamed) members were communists or not, and that in any case, he thought the union had them under control.(Later his first wife, actress Jane Wyman stated in her biography with Joe Morella (1985) that Reagan’s allegations against friends and colleagues led to tension in their marriage, eventually resulting in their divorce). Actor Adolphe Menjou declared, “I am a witch hunter if the witches are Communists. I am a Red-baiter. I would like to see them all back in Russia.”

In contrast, several leading Hollywood figures, including director John Huston and actors Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Danny Kaye, organized the Committee for the First Amendment to protest the government’s targeting of the film industry. Members of the committee, such as Sterling Hayden, assured Bogart that they were not Communists. During the hearings, a local Washington paper reported that Hayden was a Communist. After returning to Hollywood Bogart shouted at Danny Kaye, “You [expletive] sold me out.”The group came under attack as being naive or foolish. Under pressure from his studio, Warner Brothers, to distance himself from the Hollywood Ten, Bogart negotiated a statement that did not denounce the committee, but said that his trip was “ill-advised, even foolish.” Billy Wilder told the group that “we oughta fold.”

Huston later changed his opinion of the Hollywood Ten. In a 1952 letter he told a colleague: “It was a long time afterward that I discovered that the real reasons behind the behavior of the ‘Ten’ in Washington, and when I did I was shocked beyond words. It seems that some of them had already testified in California, and that their testimony had been false. They had said they were not Communists and now, to have admitted it to the press would have been to lay themselves open to charges of perjury … And so, when I believed them to have engaged to defend the freedom of the individual, they were really looking after their own skins. Had I so much as suspected such a thing, you may be sure I would have washed my hands of them instantly. But, as I said before, the revelation was a long time coming.”

Many of the film industry professionals in whom HUAC had expressed interest—primarily screenwriters, but also actors, directors, producers, and others—were either known or alleged to have been members of the American Communist Party. Of the 43 people put on the witness list, 19 declared that they would not give evidence. Eleven of these nineteen were called before the committee. Members of the Committee for the First Amendment flew to Washington ahead of this climactic phase of the hearing, which commenced on Monday, October 27. Of the eleven “unfriendly witnesses”, one, émigré playwright Bertolt Brecht, ultimately chose to answer the committee’s questions.

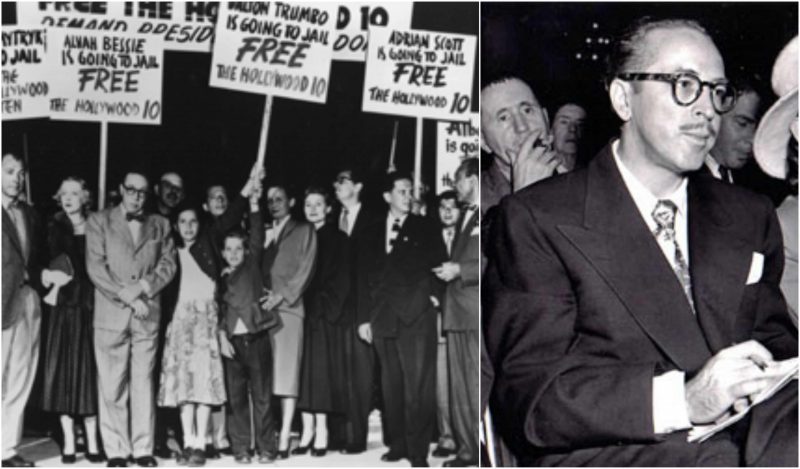

The other ten refused, citing their First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and assembly. The crucial question they refused to answer is now generally rendered as “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Each had at one time or another been a member, as many intellectuals during the Great Depression felt that the Party offered an alternative to capitalism. Some still were members, others had been active in the past and only briefly. The Committee formally accused these ten of contempt of Congress and began criminal proceedings against them in the full House of Representatives.

In light of the “Hollywood Ten”‘s defiance of HUAC—in addition to refusing to testify, many had tried to read statements decrying the committee’s investigation as unconstitutional—political pressure mounted on the film industry to demonstrate its “anti-subversive” bona fides. Late in the hearings, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), declared to the committee that he would never “employ any proven or admitted Communist because they are just a disruptive force and I don’t want them around.” On November 17, the Screen Actors Guild voted to make its officers swear a pledge asserting each was not a Communist.

The following week, on November 24, the House of Representatives voted 346 to 17 to approve citations against the Hollywood Ten for contempt of Congress. The next day, following a meeting of film industry executives at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel, MPAA president Johnston issued a press release that is today referred to as the Waldorf Statement. Their statement said that the ten would be fired or suspended without pay and not reemployed until they were cleared of contempt charges and had sworn that they were not Communists. The first Hollywood blacklist was in effect.

A key figure in bringing an end to blacklisting was John Henry Faulk. Host of an afternoon comedy radio show, Faulk was a leftist active in his union, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. He was scrutinized by AWARE, one of the private firms that examined individuals for signs of Communist sympathies and “disloyalty.” Marked by the group as unfit, he was fired by CBS Radio. Almost alone among the many victims of blacklisting, Faulk decided to sue AWARE in 1957. Though the case would drag through the courts for years, the suit itself was an important symbol of the building resistance to the blacklist.

The initial cracks in the entertainment industry blacklist were evident on television, specifically at CBS. In 1957, blacklisted actor Norman Lloyd was hired by Alfred Hitchcock as an associate producer for his anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, then entering its third season on the network. On November 30, 1958, a live CBS production of Wonderful Town, based on short stories written by then-Communist Ruth McKenney, appeared with the proper writing credit of blacklisted Edward Chodorov, along with his literary partner, Joseph Fields. The following year, actress Betty Hutton insisted that blacklisted composer Jerry Fielding be hired as musical director for her new series, also on CBS. The first main break in the Hollywood blacklist followed soon after: on January 20, 1960, director Otto Preminger publicly announced that Dalton Trumbo, one of the best known members of the Hollywood Ten, was the screenwriter of his forthcoming film Exodus. Six-and-a-half months later, with Exodus still to debut, the New York Times announced that Universal Pictures would give Trumbo screen credit for his role as writer on Spartacus, a decision star Kirk Douglas is now recognized as largely responsible for. On October 6, Spartacus premiered—the first movie to bear Trumbo’s name since he had received story credit on Emergency Wedding in 1950. Since 1947, he had written or co-written approximately seventeen motion pictures without credit. Exodus followed in December, also bearing Trumbo’s name. The blacklist was now clearly coming to an end, but its effects continue to reverberate even until the present.

John Henry Faulk won his lawsuit in 1962. With this court decision, the private blacklisters and those who used them were put on notice that they were legally liable for the professional and financial damage they caused. This helped to bring an end to publications such as Counterattack. Like Adrian Scott and Lillian Hellman, however, a number of those on the blacklist remained there for an extended period—Lionel Stander, for instance, could not find work in Hollywood until 1965. Some of those who named names, like Kazan and Schulberg, argued for years after that they had made an ethically proper decision. Others, like actor Lee J. Cobb and director Michael Gordon, who gave friendly testimony to HUAC after suffering on the blacklist for a time, “concede[d] with remorse that their plan was to name their way back to work.” And there were those more gravely haunted by the choice they had made. In 1963, actor Sterling Haydendeclared,

I was a rat, a stoolie, and the names I named of those close friends were blacklisted and deprived of their livelihood.

Scholars Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner state that Hayden “was widely believed to have drunk himself into a near-suicidal depression decades before his 1986 death.”

Into the 21st century, the Writers Guild pursued the correction of screen credits from movies of the 1950s and early 1960s to properly reflect the work of blacklisted writers such as Carl Foreman and Hugo Butler. On December 19, 2011, the guild, acting on a request for an investigation made by his dying son Christopher Trumbo, announced that Dalton Trumbo would get full credit for his work on the screenplay for the 1953 romantic comedy Roman Holiday, almost sixty years after the fact.