Is it a car? – Kind of. Is it a boat- Kind of! It’s the fastest car on the water and the fastest boat on the road, it’s the ambitious car-boat hybrid named Amphicar. While Time declared it as one of the worst cars in history by describing it as “.

A vehicle that promised to revolutionize drowning,” we think it’s a genius solution for those who can afford to own both car and boat(tongue in cheek speaking, obviously).

However, this car or this boat, it’s a riot, especially for me, who doesn’t have the slightest knowledge or interest in cars.

Designed by Hanns Trippel, the amphibious vehicle was manufactured by the Quandt Group at Lübeck and at Berlin-Borsigwalde, with a total of 3,878 manufactured in a single generation.

A descendant of the Volkswagen Schwimmwagen, the Amphicar offered only modest performance compared to most contemporary boats or cars, featured navigation lights and flag as mandated by Coast Guard — and after operating in water required greasing at 13 points, one of which required removal of the rear seat.

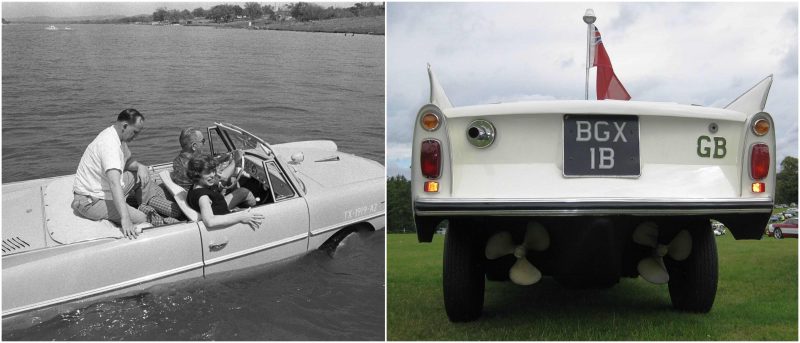

The front is slightly pointed and sharply cut away below. The wheels are set low so that the vehicle stands well above ground level when on dry land.

Front and rear bumpers are placed low on the body panels (but fairly high in relation to dry ground). The one-piece windshield is curved.

The foldable top causes the body style to be classified as a cabriolet. Its water propulsion is provided by twin propellers mounted under the rear bumper.

The powerplant was the 1147 cc (69 in³) engine from the British Triumph Herald 1200. Many engines were tried in prototypes, but the Triumph engine was “state of the art” in 1961 and had the necessary combination of performance, weight, cool running and reliability.

Updated versions of this engine remained in production in the Triumph Spitfire until 1980. The Amphicar engine had a power output of 43 hp (32 kW) at 4750 rpm, slightly more than the Triumph Herald due to a shorter exhaust.

Designated the “Model 770”, the Amphicar could achieve speeds of 7 knots in the water and 70 mph (110 km/h) on land.

Later versions of the engine displaced 1296 cc and 1493 cc and produced up to 75 bhp (56 kW). Some Amphicar owners have fitted these engines to improve performance.

One owner was quoted “It’s not a good car and it’s not a good boat, but it does just fine” largely because of modest performance in and out of the water.

Another added, “We like to think of it as the fastest car on the water and fastest boat on the road.”

In water as well as on land, the Amphicar steered with the front wheels, making it less manoeuvrable than a conventional boat. Time’s Dan Neil called it “a vehicle that promised to revolutionize drowning”, explaining, “Its flotation was entirely dependent on whether the bilge pump could keep up with the leakage.”

In reality, a well maintained Amphicar does not leak at all and can be left in water, parked at a dockside, for many days.