In California in the 1600s, Loggers were required to cut down redwood trees, some aged up to 1500 years old.

After the logs were separated, they were hitched to oxen and taken to the rivers for transport to riverside sawmills.

Hardwood logs that were not able to go downriver were chained to buoyant softwoods and rafted to mills for processing.

Many of the logs that were floated downriver became waterlogged, or were caught in a log jam and ultimately sank to the bottom of the stream.

Once the logs sank they were preserved in the river bottoms.

The minerals in the water where the logs rested played an important part in the color of the finished lumber.

Many factors can harm the quality of the logs; oxygen, direct sunlight and pests. However, while resting underneath the water they were being protected from these enemies.

After centuries, the sunken treasure has finally been recovered.

These logs are prized for their possible uses, including flooring and paneling due to the wood’s tight grain, rich color and intriguing grain patterns.

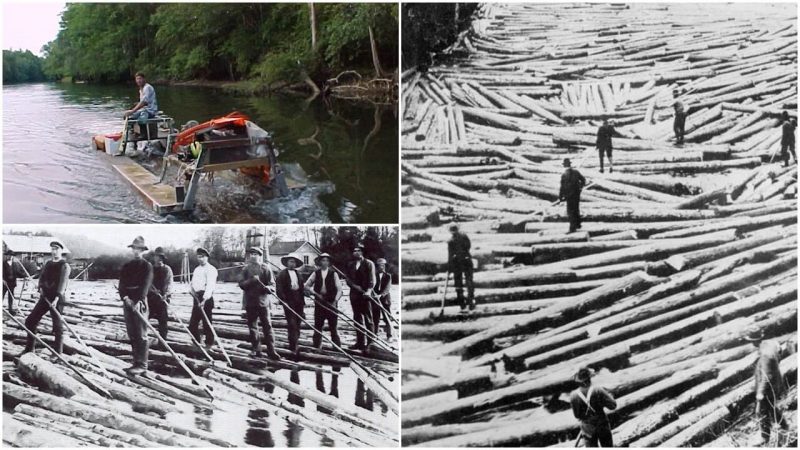

DeadHead Lumber Company has been focused on reclaiming the sunken logs from Maine rivers and lakes.

Because the weather on northern Maine lakes and rivers changes so quickly and dramatically, many of the rafts transporting the logs were either lost or abandoned during the storms.

The rivers and lakes served as highways for moving the logs from forest operations to sawmills.

It is now estimated that one out of every ten logs that floated on the commercial waterways sank to the bottom, before reaching their destination in North America.

Logs that sank to the bottom of a river or lake during the logging drives of the last century, or the century before that, or even the century before that are called “old-school deadheads”.

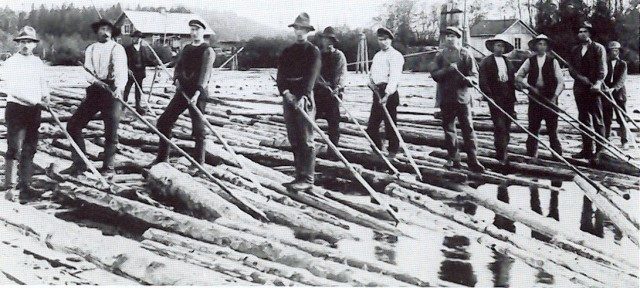

Before the railroads reached the north woods, loggers went into the forests in the winter and cut down trees with axes or cross-cut saws and dragged the logs to the river banks of the closest river.

When spring came, they would take the logs downriver to sawmills, or later papermills.

From the 1770s to mid-20th century, log dives were operated every spring, especially on the Penobscot River in Maine, which became the most important logging river in the world. Hundreds of millions feet of lumber travelled every year to the mills in Bangor, Maine.

Dangerous log jams occurred when the Penobscot was high, and water was running fast. When the water was too slow, the logs beached themselves on the rocks.

These exact same logs are now a danger to boats and fishermen.

Tommie Williams of Lyons, Maine is a Republican State Senator that sees underwater logging as a way to pay tribute to the backbreaking work of the old loggers. These numbers include four generations of his family.

“It’s really a treasure,” Williams said. “The quality of the wood and the uniqueness of the wood is something we can’t duplicate. There really aren’t any virgin forests left.”

After tying the logs together into rafts, Williams’ ancestors floated them down the Altamaha to the port of Darien, where ships waited in the harbor. “In its heyday, they say you could walk for miles on the river on the rafts waiting to be loaded”, he said.

Down at the bottom of the rivers and lakes, the logs eventually lose their bark and become slimy, but the wood is perfectly preserved in cold water and can be used in a huge number of ways.

While millions of logs are floating by on the top of the water, it is not economical to salvage the deadheads on the bottom.