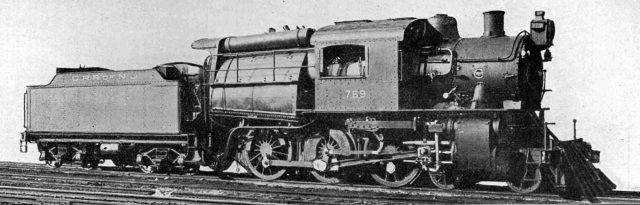

A conventional steam locomotive has a cab for the engineer and fireman behind the firebox at the rear of the boiler. The camelback locomotive has a wide firebox designed to successfully burn culm and since it was impractical to build the cab behind the very wide firebox, it was mounted astride the boiler before the firebox.

The first camelback, a 4-6-0, was built in early 1877 by the P&R’s Reading, Pennsylvania shops. It proved a success; the fuel cost saving was about $2,000 a year (approx. $30,000 in 1998 dollars). More were built for many of the railroads operating in the anthracite regions, and some others, of many different wheel arrangements.

Back in the late 19th century, anthracite or hard coal which burns slowly and with little smoke was used for home heating. Anthracite coal was only found in eastern Pennsylvania, and the railroads that hauled the coal often burned it for fuel.

This coal had to be screened to remove fine material and to carefully size the coal before shipping it from the mines. The waste of anthracite known as culm, which resulted from handling and preparation, was piled high at the mines and amounted to almost 20% of production and had no commercial value.

It was at the time when John E. Wootten became the General Manager of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. He had watched the piles of waste grow into small mountains and wanted to find a way to use this plentiful resource. So, he experimented with culm to find a way to use this abundant and cheap fuel.

He concluded that a very low firing rate worked best and the Reading began to use culm in stationary boilers at its shops and stations. Culm did not burn well in the long narrow fireboxes that were typically located between the frames of the locomotives of the day. A thick fire is required in these fireboxes and the heavy draft needed to keep them burning would blow the fine coal off the grate.

So, Wootten came up with an idea to create a locomotive that can use the culm for fuel. He designed a locomotive with a revolutionary firebox and boiler design that featured a cab that basically straddled the middle of the boiler. This locomotive was called a Camelback, or sometimes a double-cab locomotive, center-cab locomotive or a Mother Hubbard.

Even though Baltimore & Ohio Railroad developed something similar to the later Camelback in the 1840s, given the interesting name of “Muddiggers,” it didn’t catch on until Wootten patented his design in 1877.

The engineer’s cab of Wootten’s locomotive was placed above and astride the boiler making the engineer unprotected from the possible broken driving rod, while the fireman remained at the rear having to balance himself on a moving platform while stoking the fire and being exposed to the elements.

This steam locomotive with the driving cab placed in the middle, astride the boiler was unsafe, but at that moment cheap fuel was much more popular than safeness, especially in anthracite mining regions.

The camelback was an ideal passenger locomotive because the hard coal burned almost without smoke. Some impressive speeds were obtained with these locomotives as very often they would turn un an average speed of under a mile a minute.

Camelbacks became fantastically popular with the railroads which staked their livelihoods on the resource (names like Central Railroad of New Jersey; Delaware, Lackawanna & Western; Lehigh Valley; Lehigh & New England Railroad; and the Lehigh & Hudson River). Other lines which came to use the Camelback design included the B&O, Erie, Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, Santa Fe, Pennsylvania, Wheeling & Lake Erie, and Maine Central.

However, due to the inherent dangers with the design of the Camelbacks, the Interstate Commerce Commission instituted (ICC) a ban that ceased production of the locomotives; however, a few exceptions were made up through the early 1920s. It wasn’t until 1927 when the ICC finally hammered the proverbial nail in the Camelback’s coffin, banning any future orders for the versatile but dangerous locomotive.