In November 1918 the WWI was finally over. The last ceasefire was signed between the Germans and the French in the so-called Compiègne Wagon. Inability to resolve the huge economic crisis of the 1930s inflamed the already existing dissatisfaction with ‘democracy’ and ‘pacifism’ among military officers on both sides of the Franco-German border. A decade later, a new global war was raging.

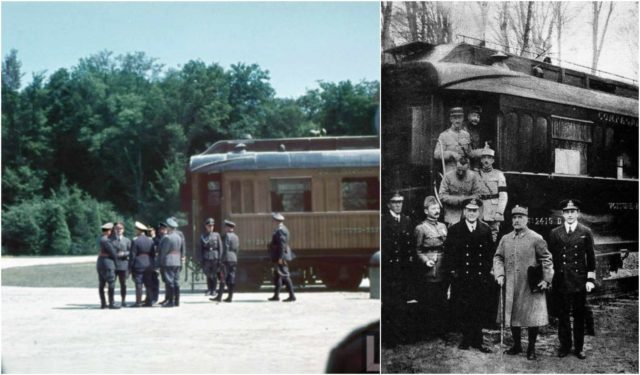

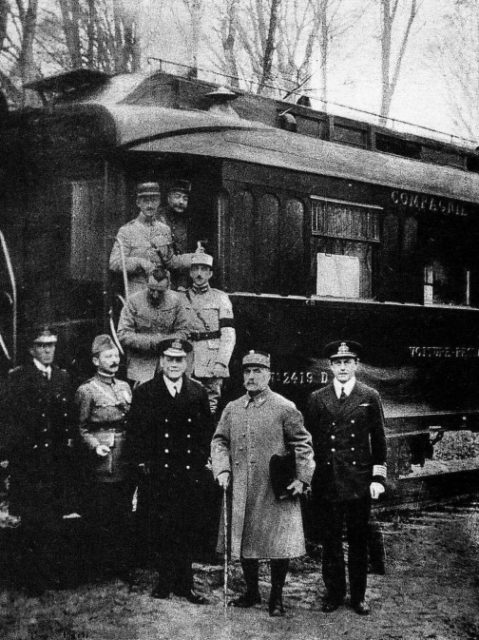

This is a story of an unlikely train wagon that remains the symbol of this wild power struggle. Compiègne Wagon was originally built in 1914 to serve as a dining car. Four years later it was adjusted so that it could host an office for the French Marshal Ferdinand Foch. On 11 November 1918 it was to become an unlikely historical site. Marshal Foch and his German counterpart sat between its walls ad signed the German Empire’s final surrender. Well, not so final.

Over the coming years, discontent among many German military officers grew. Unwilling to accept defeat, they eventually formed the notorious Freikorps, something of a precursor to the Nazi Party. Among other things, they opposed the truce previously signed with the Allied Powers. On the other side of the border, French Marshal Philippe Pétain slowly rose to power. In the final years of WWI, he served as Commander-in-Chief of the French Army. Ideologically, he despised the Republic and advocated for the restoration of ‘traditional’ values, a strong, authoritarian and unified state. In 1939 WWII broke out.

French forces suffered massive defeat against Germans in the Battle of France during the first half of 1940. Their government escaped from Paris to Bordeaux and effectively remained powerless. From May to July 1940, Marshal Pétain, politically compatible with the German enemy, advanced from being a Deputy Prime Minister to the Chief of the French State. French Republic was no more.

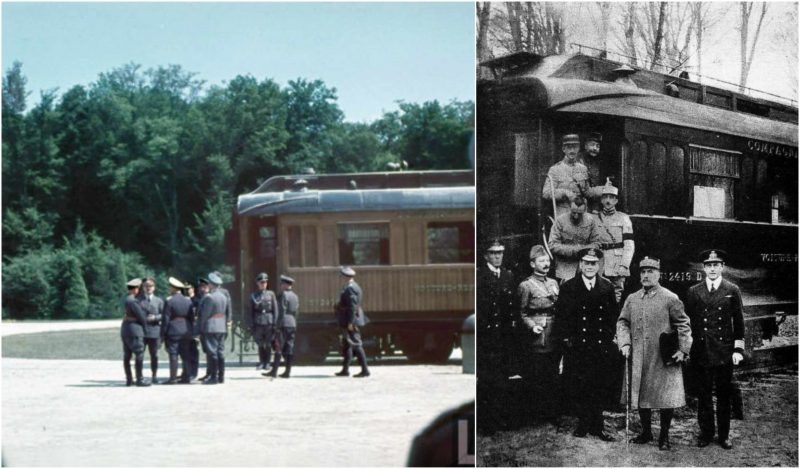

France was forced to surrender and its somewhat exiled government offered Hitler to negotiate the truce. In line with his well-known eye for symbolism, Hitler decided that the best place to sign the document was the very place where Germany surrendered 22 years ago. The Compiègne Wagon. Despite claiming that he “does not have the intention to use the armistice conditions and armistice negotiations as a form of humiliation” of France, that is exactly what happened.

First, the train had to be relocated from a specially designed museum to commemorate the truce of 1918 – even if it meant actually moving it just a couple of meters down the road. Hitler first decided to sit in the same chair which Marshal Foch had sat in the previous episode of this decades-long arm wrestle. Very soon he left the negotiations, in an intentional move to show off as the final victor. Practically the whole northwest of France was occupied, while the rest was left for Hitler’s companion Pétain to administer, according to rules and regulations (and symbolic) that were reminiscent of a Fascist and Nazi rule. For the next five years around one million French soldiers remained German POWs. This was not an armistice – it was a revenge served cold.

After the capitulation, the hero of our story traveled around Germany like enemy’s head on a stick. The symbolism was clear enough – we claimed that if we get to power Germany will finally prevail, and it did. Well, not for long. In March 1945, with their defeat creeping, the SS troops blew up the wagon. A month later Hitler followed suit. The war was over.

Fortunately or not, new armistice needed to be signed elsewhere. Remains of Compiègne Wagon were dug up from the ground and later restored by German POWs. Today it once again rests at the museum Clairière de l’Armistice, hopefully for good.