“Why aren’t we exploring the oceans?…It contains more human history than all the museums on Earth combined” – Robert Ballard

Here are some of the shipwrecks that “haunt” the archaeologists and which wait to be discovered.

1. Santa Maria

On his famous voyage of 1492 to the American continents (or in his mind India) Christopher Columbus set sail with three ships – La Nina (or ‘The Girl’), La Pinta (‘The Painted’) and The Santa Maria. Santa Maria was 36 meters long, was the largest one, the leading one and the ship that never returned to Spain. Apparently, on that Christmas Evening the sailor charged with steering the flagship Santa Maria handed the wheel over to an inexperienced cabin boy, who promptly ran the vessel onto a coral reef near modern day Haiti.

Realizing that the ship cannot be repaired the crew saved most of the cargo from the ship and Columbus ordered them to strip the timbers from it which were later used for building a fort that Columbus called La Navidad (Christmas). He sailed back to Spain with the other two boats leaving 39 men to establish the new fort and settlement of La Navidad.

It is believed that most of the ships’ crew was criminals who were offered amnesty from the royal decree in Spain if they joined the voyage, but only four of the men were convicts. However, when Columbus sailed back to the Caribbean next year, none of the men left there was found alive.

The precise location of Santa Maria has since been lost to history. On 13 May 2014, underwater archaeological explorer Barry Clifford claimed that he found the wrecks of Santa Maria using information from Columbus’ journals, but an examination by UNESCO experts later found proof that the wreck belonged to a different ship from the 17th or 18th centuries.

Columbus had a hard time getting his expedition funded, and none of the boats was made especially for him. And despite the legend that he managed to make deal with King Ferdinand and the Queen Isabella of Spain to bring them whatever he finds in the new land and that the Queen used a necklace that she had received from her husband the king as collateral for a loan, the truth is that his expedition was principally financed by a syndicate of seven noble Genovese bankers resident in Seville. Hence, all the accounting and recording of the voyage was kept in Seville.

2. USS Indianapolis

In late July 1945, USS Indianapolis had been on a secret mission delivering components of the first atomic bomb to the Pacific island of Tinian where American B-29 bombers were based. Just a few days after delivering the parts successfully, the warship was sailing west towards Leyte Gulf in the Philippines in order to join the battleship USS Idaho (BB-42) to prepare for the invasion of Japan when it was attacked.

At 14 minutes past midnight, on 30 of July, the warship was hit by two torpedoes out of six fired by the I-58, a Japanese submarine. A 19-year-old seaman, Loel Dean Cox, was on duty on the bridge. Later he recalled the moment when the first torpedo had hit the boat:

“Whoom. Up in the air, I went. There was water, debris, fire, everything just coming up and we were 81ft (25m) from the water line. It was a tremendous explosion. Then, about the time I got to my knees, another one hit. Whoom.”

The first torpedo blew away the bow and the second one struck near midship almost tearing the ship in half.

“I turned and looked back. The ship was headed straight down. You could see the men jumping from the stern, and you could see the four propellers still turning.

“Twelve minutes. Can you imagine a ship 610ft long, that’s two football fields in length, sinking in 12 minutes? It just rolled over and went under”, said Cox who died in 2015 at the age of 88.

And that was just the beginning of the horror. Of the 1 196 men aboard, almost 900 made it into the water in the twelve minutes before she sank. Few life rafts were released while most survivors wore the standard kapok life jacket. And with the sunrise of the first-day shark attacks began and continued until the men were rescued from the water, almost five days later.

By the time they were accidentally spotted by a Navy plane and rescued four days later, all but 317 had perished from exposure and attacks by prowling hordes of oceanic white tips. On the fourth day, they were accidentally spotted by PV-1 Ventura Bomber on routine antisubmarine patrol and the pilot who overflew the destroyer USS Cecil Doyle (DD-368) alerted her captain of the emergency. Arriving hours ahead of the Doyle, the crew of the Bomber began dropping rubber rafts and supplies. While so engaged, they observed men being attacked by sharks.

The sinking of Indianapolis is now remembered as the worst American naval disaster of World War II. Yet despite multiple expeditions using sonar and underwater vehicles, the ship’s wreckage has never been found. Part of the problem lies in the extreme depths of the search area. According to some estimates, the cruiser may rest in over 12,000 feet of water.

3. HMS Endeavour

The ship of Captain James Cook’s voyage of discovery was last seen in 1778, by which time it was being used as a transport ship during the American Revolution.

Cook commanded the ship from 1768 to 1771 on his famous voyage mapping the uncharted waters of the south Pacific Ocean, but for years, its whereabouts have remained a mystery.

The ship was the first European vessel to visit the east coast of Australia and circumnavigate New Zealand, but only a few years after returning home, it was unceremoniously sold to a private buyer. After exploring far-flung lands the boat passed through a number of different hands before it was renamed the Lord Sandwich and used in America’s revolutionary war. During the American Revolution in 1778, Endeavour was one of the 13 ships that were intentionally sunk by the British navy in order to blockade a channel in Newport harbour against an approaching French fleet.

A research team of US archaeologists from the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP) will work with the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney to confirm the remains of a ship found in the harbour belong to the HMS Endeavour. The team is headed by marine archaeologist Kathy Abbass who uncovered new documents which allowed them to narrow down the location of Endeavour in a 500-by-500-metre area.

The team has located more than two-thirds of the scuttled ships as of this year, but they have yet to find hard evidence that any of them is Cook’s long lost Endeavour.

4. Le Griffon

Build in the 1679 Le Griffon was the first full-sized sailing ship on the upper Great Lakes of North America and she led the way to modern commercial shipping in that part of the world. On its maiden voyage the ship sailed across Lake Erie, Lake Huron and Lake Michigan with a crew of 32, through uncharted waters where only canoes have sailed before.

Le Griffon was a three-masted vessel built by the French explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle during an early expedition to the North American frontier.

The ship was never seen again after it sailed in September 1679 from an island near the entrance of Green Bay (today’s northern Wisconsin), with a crew of six and a cargo of furs.

Steve Libert, a diver and shipwreck enthusiast who has searched three decades for the Griffin, told the Associated Press in 2014 that he believes he found “Le Griffon” in Lake Michigan after extensive searching, in a debris field near where a wood slab was found the previous year. Later that same year two divers, Kevin Dykstra, and Frederick Monroe, announced the discovery of a wreck that they believe is Le Griffon, based on the bow stem, which to some resembles an ornamental griffin.

Its true fate remains a mystery, though it’s commonly believed that the ship may have foundered in a storm or been scuttled by the mutinous crew.

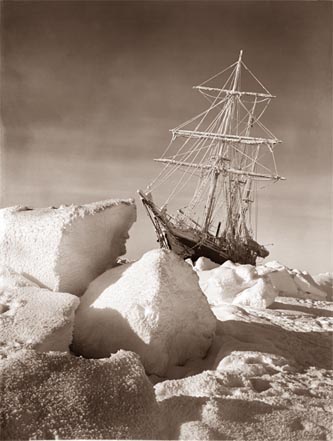

5. Endurance

Endurance was the ship of Sir Ernest Shackelton who in 1914 sailed on the Imperial Trans-Antartic Expedition. He hoped to make the first overland crossing of Antarctica but instead the ship was crushed by ice causing her to sink three years later in the Weddell Sea of Antartica.

Shackelton planned to set out from the Weddell sea region (to the south of South America) across a completely unexplored region of Antarctica, to the pole, and then to the Ross sea / McMurdo sound area (to the south of New Zealand).

Endurance was build in a Norwegian shipyard and was intended for tourist cruises in the Arctic, but instead, it endured 10 months in the heavy pack ice of the Antarctic before the pressure finally cracked it. In a meantime, the expedition managed to survive the loss of their ship in the middle of the Antarctic pack ice at a time when there was no chance of contacting the outside world, let alone of being rescued. Shackelton saved his crew by sailing 800 miles in a lifeboat.

It is believed that today Endurance‘s wrecks lay at a depth of 10 000 feet beneath a 5- foot layer of ice. Titanic discoverer Robert Ballard and the marine scientist David Mearns have expressed their interest in discovering the wrecks of Endurance but nobody has expressed interest into funding an expedition to the Antartic.

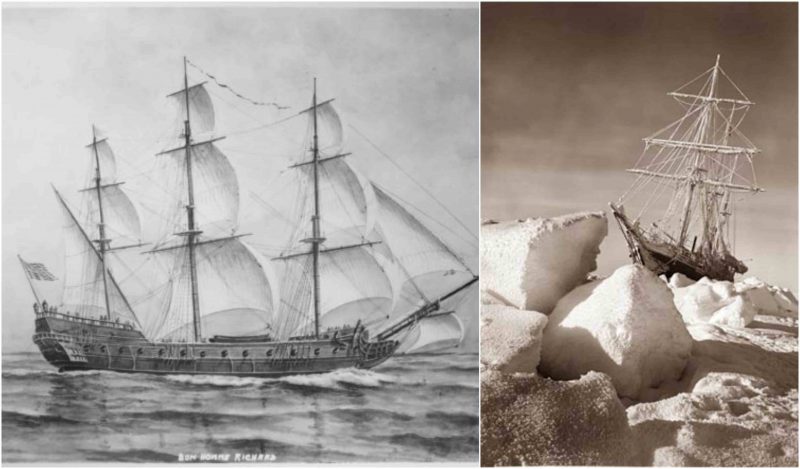

6. Bonhomme Richard

It was built as a merchant ship in France for the French East India Company in 1765. It was named The Duc De Duras and it transported freight between the Orient and France. As a result of a loan to the United States, in 1779 King Louis XVI gave the ship to the United Navy and to the Scotish-American sailor and “Father of the American Navy” – John Paul Jones. As a big admirer of Benjamin Franklin, John Paul Jones named the boat Bohomme Richard which translated in English means “The poor Richard” – the pen name Franklin used when he wrote “Poor Richard’s Almanac”.

On September 23, it squared off against HMS Serapis and another Royal Navy ship in a ferocious battle off the northeast coast of England. Brushing off an early call to surrender with the immortal words “I have not yet begun to fight,” Jones rallied his men and successfully captured Serapis after several hours of combat and the British captain was forced to surrender.

However, it was too late to save the Bonhomme Richard which had caught fire and taken several shots below its waterline. After spending 36 hours trying to keep it afloat, Jones and his crew reluctantly abandoned the ship and let it sink in the choppy waters of the North Sea.

The location of Bonhomme Richard’s wrecks is presumed to be in approximately 55 meters of water off Flamborough Head, Yorkshire, a headland near where her final battle took place.