We often forget how things come to be. Some may remember the legendary Amiga computer, but younger generations would make no connection whatsoever with today’s iPhones. Same goes for military history – or any kind of history for that matter. This is a story of modern tank’s forgotten ancestor, the ironclad warship.

Back in the 19th-century competition was raging between two traditional European rivals and huge military forces – the United Kingdom and France. Wars were fought primarily on land, but also at sea. The British Naval forces were far superior and French were struggling to catch up. Same as in rapidly expanding industry, technological innovations were quickly changing the rules of the game. The capitalist competition was at large, somewhat comparable to the state of today’s IT sector. Little did the actors at the time know that their more or less ad hoc improvements of warships would change the course of war history altogether.

Enter mid-1850s and the late age of wooden warships. Those were pretty prone to sinking after being pierced through with shells, as one might figure. Back in the day, naval tactics could still mostly be summed up as such: get as many ships as you can, form a line, and shoot to sink as many of the opposing force’s ships as you possibly can. Last fleet standing wins.

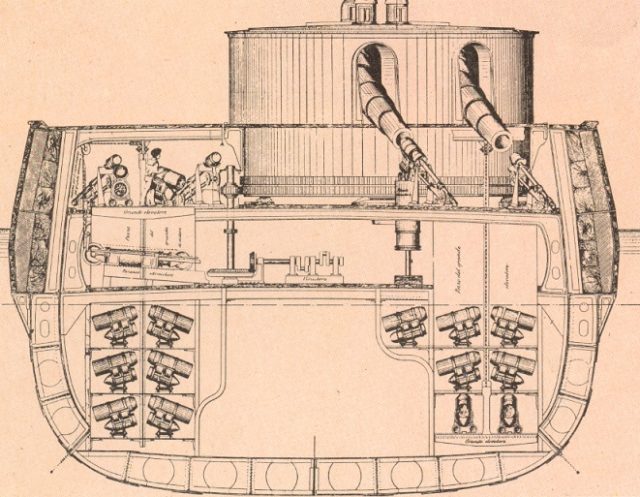

Industrial and technical innovations made possible advances in this field. As the naval historian J. Richard Hill notes, three factors proved necessary for decisively moving away from this kind of naval warfare: “a metal-skinned hull, steam propulsion and the main armament of guns capable of firing explosive shells.” Armor the ships, make them independent of wind flow and mount them with the biggest guns possible. All three were being incorporated into warship building since the beginning of the century, but it hadn’t all come together until the French, desperately trying to outmaneuver the English, built their ship Galore in November 1859. Et voila, the first ironclad ship was borne and with it, the new field of fierce competition and allocation of valuable resources towards the war industry.

One would be tempted to say that the rest is history, but this story doesn’t reach the climax on its own. History of the ironclads runs through the second half of the 19th century and kind of fades away. Why so? Well, on the one hand, even though they proved their efficacy at sea, most battles and wars were still being fought and resolved on ground. On the other hand, the invention of stronger and more durable warships made a whole lot of mess on the field of naval tactics.

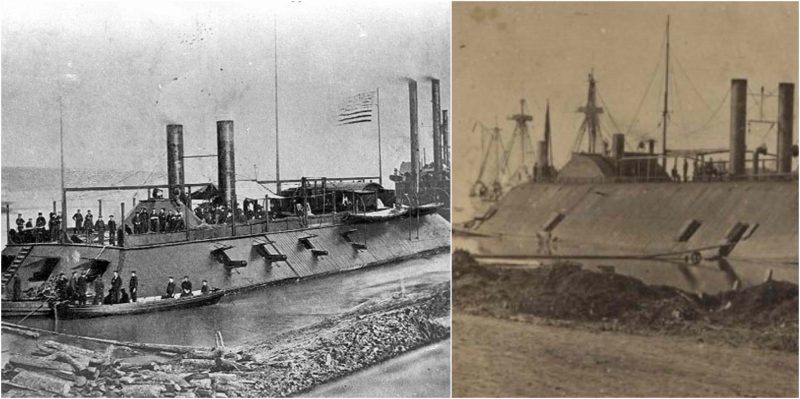

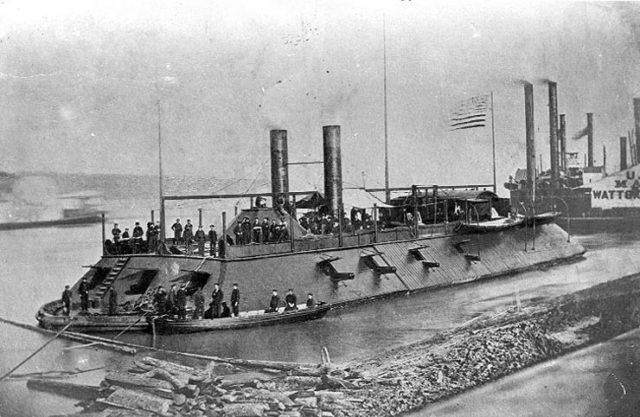

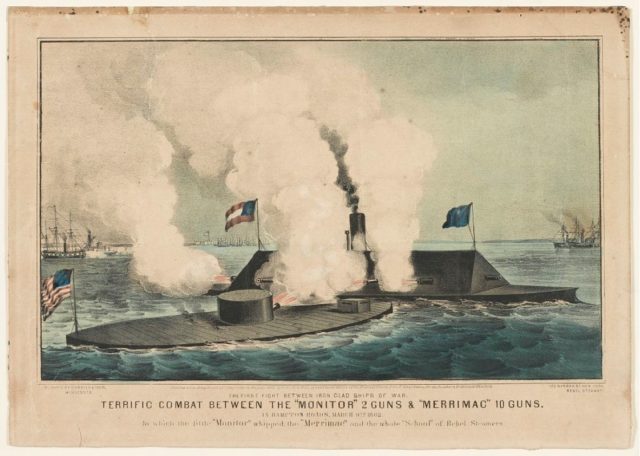

Two of the most prominent wars where ironclad ships found their meaning of existence didn’t even involve Britain or France. One was the great American Civil War (1861–1865) and the other was historically less significant Battle of Lisa, fought between Italian and Austrian fleets in 1866. Both proved important for the development of ironclad’s structure and possibilities, or rather to the transition to the full-on battleships of today. Oh, tanks as well.

The idea of a ship being resistant to enemy fire obviously opened up new horizons. But once most of the relevant naval forces acquired ironclad warships a new problem arose – how does either one of them ever win the battle? Thus ensued further development of naval armament, strong enough to pierce through the opponent’s armor. This posed various difficulties, least of which is the fact that the competition drove all of the leading forces to perfect the alloys they cover their ships in. For a time being it was thought that there will be a revival of ramming technique, where one ship attempts to sink another by piercing its hull via an underwater prolongation of the ship’s boat. Even though there was little proof of this technique being effective in ironclad clashes, the notion was widespread.

Nevertheless, as is often the case, this problem gave way for some creatively destructive ideas. Thus the decades-long experimenting with different types of torpedoes. The first torpedoes were static mines, some of which proved useful for sinking Confederate ironclads. But the Civil War was a fertile ground for developing this further into a spar torpedo. This kind of explosive missile could be used by a smaller and agiler boat, so for the first time, the size didn’t really matter anymore. Despite the constant work in progress, larger and more equipped ironclads were still very heavy and tended to be slower than desired.

Their basic construction was usually made of wood or iron. Both had their pros and cons. So, for example, wooden hulls would need a long period of seasoning before they could be put to practice. On the other hand, iron was prone to malfunctions and countries like France seriously lacked in iron reserves. In 1870s steel was incorporated into the shipbuilding industry. It was another small revolution within a small revolution. Steel proved to be both lighter and more durable. Steel had also been tested as an armor material a decade earlier, but it proved to be too brittle on its own. Further alloys and improvements led to it being the ultimate material in shipbuilding.

The history of ironclad warships might seem more like a not so significant episode in broader military history. But that is not the case. Even if the very term ‘ironclad’ dropped out of use by the 1890s, being replaced with terms such as ‘battleship’, or ‘dreadnought’, its role extends far beyond the naval operations. These were the first heavily armored war machines ever to be used. These became an inspiration for land ships and other armored vehicles, precursors of modern day tanks. The British and French rivalry remains the issue for historians, but the products of their competition continue to shape the world today.