In the midst of WWII, far off in the mountains of New Hampshire, something strange was taking place. A group of enemy POWs was forging strong links with their guards, foremen, and the local community. The unlikely story of Camp Stark would redefine the meaning of war and camaraderie for many.

Our story begins in 1986, when a Dartmouth College professor of History, Allan Koop, set out on a trip to Germany. He was determined to find as many of the former POWs as he could and interview them for a book about the little known Camp Stark. He didn’t just mean to publish an academic work, but to honor the memory of their unique experience.

Thus he managed to persuade five of them to return to the US for the first out of many future reunions between former prisoners and guards. The very same year, the first German-American Friendship Day was organized.

In 1998, his book – “Stark Decency, German Prisoners of War in a New England Village” – was published. Within its pages lies an abundance of great, heartwarming, and at times bizarre recollections of prisoners, guards, foremen, and locals. But, let us start from the beginning.

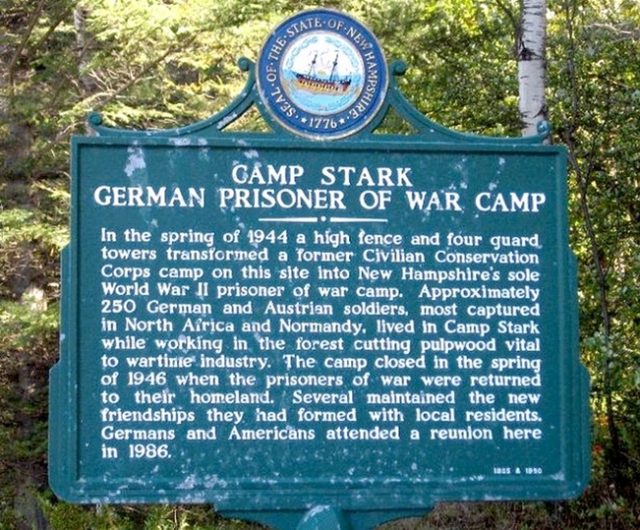

Welcome to Stark, New Hampshire, a remote logging town located some 30 miles from Canadian border. During the 1940’s its population was around 400 people. Their only experience of the war was the usual rationing of food and tobacco. In spring of 1944, that was to be changed.

On the other side of the globe, battles were raging in Tunisia as part of the broader North African Campaign which saw heavy combat between the Allies and the Axis. As the campaign dragged on, the Third Reich began to run out of soldiers. In October 1942, Hitler decided to raid German prisons and concentration camps in order to form a penal military unit, the 999th Afrika Brigade. It was made up mostly of political prisoners – Communists and Socialists who prior to the war fought against Nazism. Their purpose was to serve as a human shield between the combating forces, led by Britain and Germany.

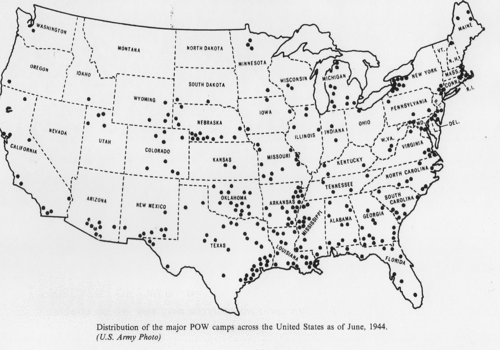

By the time they got to be sent to the front lines, the Axis had suffered a decisive defeat in North Africa. The few battalions that did get to Tunisia gladly surrendered to the British troops. More victories meant more prisoners of war for the allies, by September 1943 160,000 POWs had been transported to camps in the United States.

Some of them were Anti-Nazis who were forced to serve, but they ended up in prisons nonetheless. Once admitted, they were subjected to the same vicious treatment they had only just escaped. Their fellow Nazi POWs threatened, intimidated, and even killed them. The US Army didn’t pay much attention until the things started getting out of hand and the opposed sides were eventually segregated into different camps.

The American war efforts were making running a business ever tougher for many since the workforce was fighting overseas. Among the stricken companies were the Brown Paper Co., a pulp, and paper-making company. It was in desperate need of woodcutters. Using political ties it managed to secure for itself some POW labor in exchange for the company building a new POW camp.

The company found an abandoned camp in the town of Stark, N.H. and swiftly refitted it to serve as a prison. In early April 1944, the first round of one-hundred German and Austrian POWs boarded the trains and left the overcrowded Fort Devens camp for the newly established Camp Stark.

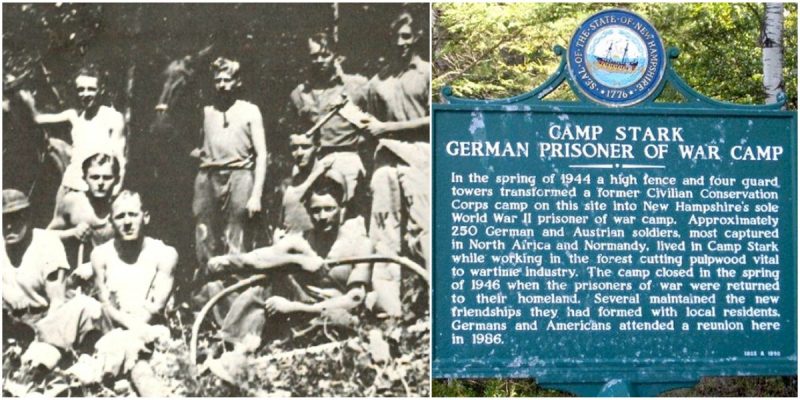

They were met by a group of curious and anxious locals who didn’t really know what to expect from their first contact with the enemy. They probably didn’t get what they expected. Most of the newcomers were soldiers of the 999th Afrika Brigade. They were generally not how one would imagine the enemy.

Among them one could find some very interesting, well-educated, cosmopolitan and open-minded figures – artists, newspaper editors, leftist politicians, doctors. In other words, this quiet provincial town basically received a gift from the heavens. During the course of the next two years of camp’s existence, a total of around 250 POWs integrated into this community.

This unlikely social mixture, gathered in a tiny town no one ever heard of, provided countless examples of solidarity and humanity unseen within a broader frame of war that set their nations against each other. That is when they weren’t out in the woods chopping trees.

Even though Camp Stark housed some real Nazis as well, they were in a minority and unable to impose the terror seen in other camps. Moreover, they were forced to accept the very same conditions they detested. So, for example, the German cook prepared special meals for Sgt. Ted Tausig, US Army’s interpreter. Tausig was an Austrian Jew who fled the Nazi regime.

The prisoners gave out tobacco to their fellow Brown Paper Co. workers and handmade toys to their kids. The camp’s German doctor was even doing rounds through Stark, treating locals, as well as some guards. In return, guards and foremen treated them with the utmost respect and even helped them saw wood when they couldn’t meet the quotas.

But they still lived imprisoned and many tried to escape. The most bizarre story is of a man called Franz Bacher, who first became popular in Stark for painting portraits of the guards and townspeople.

He was a 27-year-old Austrian left-wing activist and painter, who spent years in Nazi prisons. One day he simply disappeared into the woods, leaving a note that read: “I am going to escape today. The reason I am doing this is I live for my art. If I continue to cut wood, my hands will become so mutilated that I will be unable to paint. If I can’t paint, I can do nothing.”

He ended up in New York City, making a living by selling his works in Central Park. One day, while walking through the Penn Station he stumbled upon a friend from the camp – Sgt. Tausig, who was on a short leave. While in camp, they realized that they used to live only a few blocks apart in Vienna. They chatted and then parted. Some days later, FBI arrested Bacher and sent him back to Fort Devens.

Decades later, professor Koop’s efforts rescued this remarkable experience from oblivion. Camp Stark is no more, but the bonds forged between 1944 and 1946 last for generations. Today, even grandchildren of former prisoners visit the reunions organized in Stark. A reminder of what makes a friend and what makes an enemy. In 1988, a former POW, Francis Lang, wrote a poem whose final verses read:

“These young boys now grey-haired men,

Had learned to make amends,

Those enemies from a distant past,

Had now become good friends.

There’s nothing where the camp once was,

Just a plaque that reads with pride,

An equal tribute to those men,

Who came from either side.”