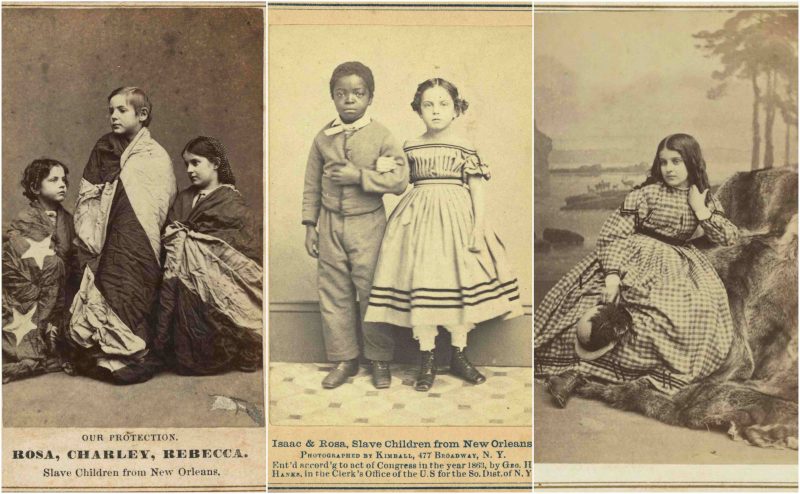

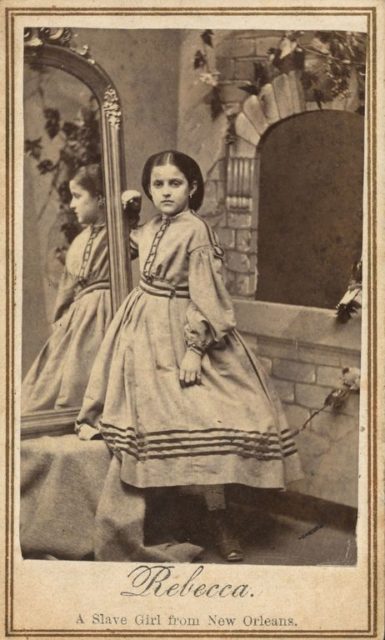

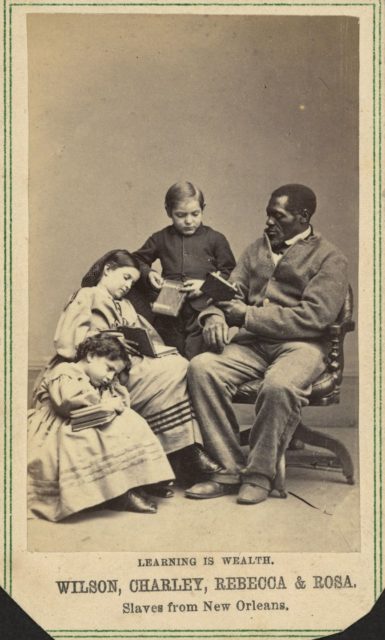

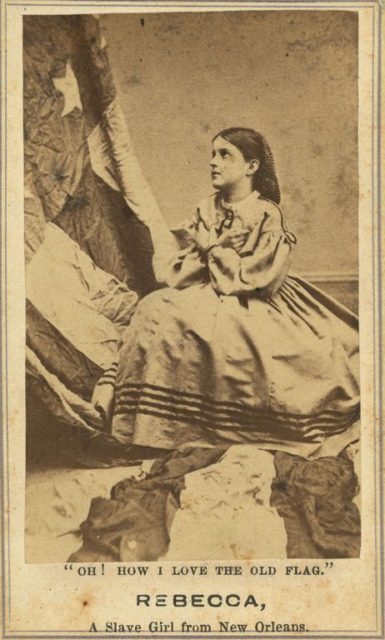

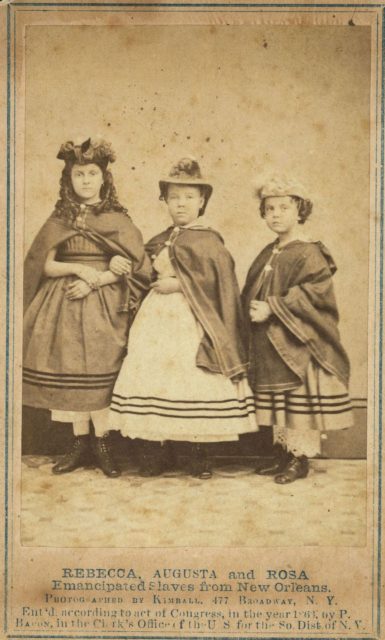

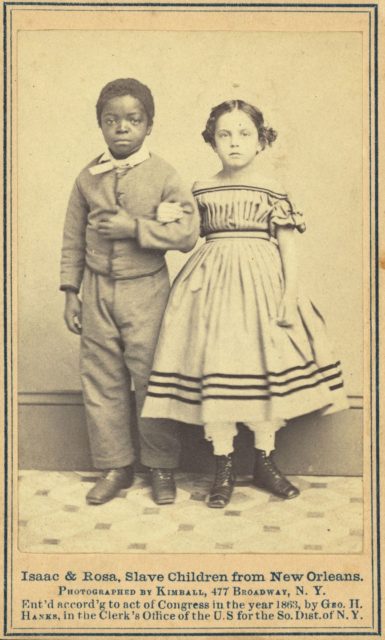

These startling photos that you are about to see below of emancipated slave children from New Orleans were used for the purposes of a campaign to raise money for their education.The campaign was called White slave propaganda and consisted of images of light-skinned former slaves during the American Civil War to elicit sympathy from northern whites.

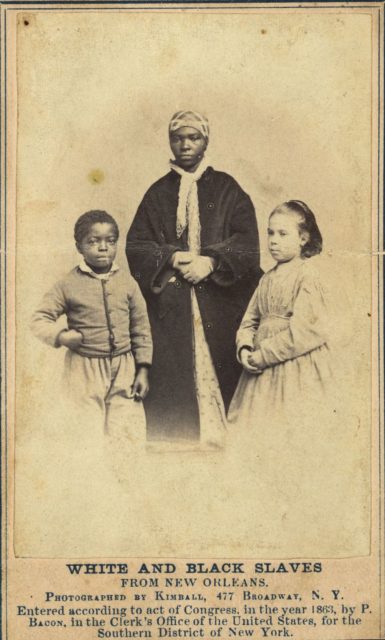

The images themselves consisted of light-skinned slave children photographed alongside dark-skinned adult slaves in an attempt to make the children look Caucasian. In turn, the hope was that northern whites would purchase the photographs of the children to help fund the education of former slaves in liberated parts of Louisiana. All Photos by Library of Congress

In December 1863, a large portion of the state of Louisiana was controlled by the Union Army. In this region, there were ninety-five schools, containing 9,500 students. Due to the strain of the war, extra funding was needed to continue to run the schools. As a result, the National Freedman’s Association, in collaboration with the American Missionary Association and sympathizing Union officers, launched a campaign in which five children and three adults who were all former slaves were sent to the north on a publicity campaign accompanied by Colonel George H. Hanks. A woodcut of them was commissioned and appeared in Harper’s Weekly in January 1864 with the caption “EMANCIPATED SLAVES, WHITE AND COLORED.”

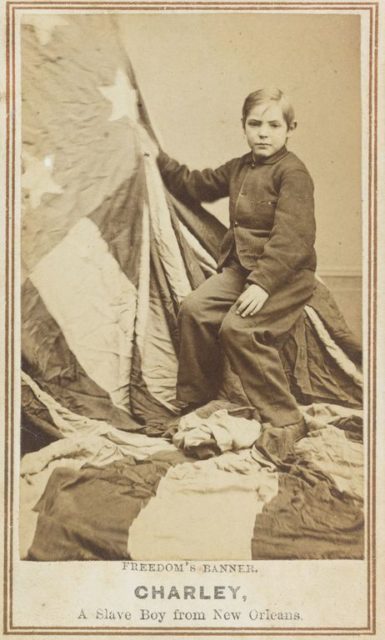

Eight persons were transported from New Orleans to the North. Of these, four children appeared to be white. According to the Harper’s Weekly article, they were, “‘perfectly white;’ ‘very fair;’ ‘of unmixed white race.’ Their light complexions contrasted sharply with those of the three adults, Wilson, Mary, and Robert; and that of the fifth child, Isaac—’a black boy of eight years; but nonetheless [more] intelligent than his whiter companions.'”

The group was accompanied by colonel from the 18th Infantry Regiment, and posed for photos at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and in Philadelphia. The resulting images were produced in the small format of carte de visite and were sold for a quarter each, with the profits of the sale being directed to Major General Nathaniel P. Banks back in Louisiana. On each of the photos, it was explained that the proceeds from the sale would be “…devoted to the education of colored people…”

Of the many prints that were commissioned, at least twenty-two remain in existence today. Most of these were produced by Charles Paxson and Myron Kimball, who took the group photo that later appeared in Harper’s Weekly.

Modern scholars have recently begun investigating the causes of the White slave campaign’s success. Mary Niall Mitchell in “Rosebloom and Pure White, Or So It Seemed,”has argued that because the slaves were depicted as being white through both their skin color and style of dress, this meant that the argument could be made that the war was independent of class status, something which was needed after the draft riots in New York City that year.

Carol Goodman in “Visualizing the Color Line,” has argued that the photos stemmed from allusions of physical abuse, an argument which is strengthened when paired with the comments of the editor of the Harper’s Weekly article when they said, that it permits slave-holding, “‘gentlemen’ [to] seduce the most friendless and defenseless of women.” Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, in “Portraits of a People,” has argued that the usage of props such as the American flag and books helps to not only make the photo relateable to Northern whites, but also show that the purpose of the photos are for education and the raising money for schools in Louisiana.