Longswords, or spathas, were more than just powerful and deadly weapons.

They were also highly-valuable status symbols and, more often than not, works of art created by highly-skilled craftsmen. Those longswords that survive as artifacts tell a story of culture, artistry, warfare, religious ritual, burial customs, law, and even taxes.

During Charlemagne’s rule (768 to 814 AD), a longsword with a scabbard was valued at seven solidi, the currency of the time. We know this by referencing the Lex Ribuaria, which was a set of laws that detailed, among other things, how people could pay their taxes.

Taxes were often paid in kind rather than with currency, so the value of trade goods was pre-determined. It’s interesting that the price of a sword without a scabbard was only three solidi, indicating that a scabbard was the more valuable part of the set. By comparison, a healthy horse was valued at seven solidi, but a healthy cow only one solidi.

Since they were so valuable, swords were used almost exclusively by cavalry officers who were high born and could afford a warhorse. Although swords as weapons have been used since ancient times, the longsword was a development of the Middle Ages.

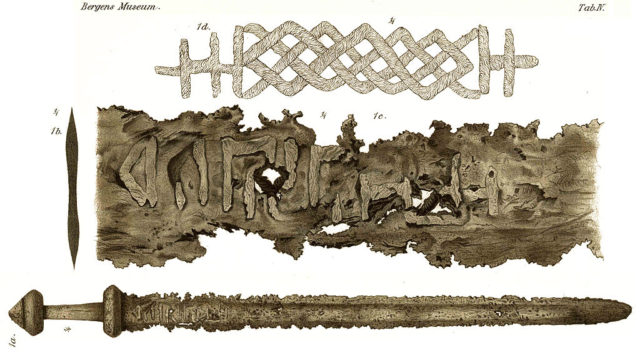

Early Viking fighters used something called a sax, which is the precursor to the Viking longsword. A sax was shorter, no more than about 24 inches as opposed to a length of up to 43 inches in the case of a longsword. Unlike the longsword, which is hilted and heavy, with a two-handed double blade, the sax is more like a long, single-edged knife.

Examples of longswords that exist today as precious relics have been recovered from graves and hoards, as well as rivers, lakes, and bogs. The Norse (Vikings) often conducted ritual sacrifice to their gods, offering valuable items like swords by depositing them in sacred water. These are some of the best-preserved swords because of the anaerobic conditions that prevented decomposition of the steel.

The exact methods and technology used for making medieval swords are not well understood. By the 9th century, however, when higher-grade steel became available, pattern welding, which had been in use for at least 600 years, became far less popular.

Continues below

Higher-quality steel allowed for blades that were narrower and tapered than older swords.

The increased tapering shifted the balance closer to the hilt, making the swords easier to wield. This was important, given the swift strikes and heavy blows necessary for hand-to-hand combat against an armored foe.

We do have some illustrated references from Carolingian times of grinders and polishers at the Abbey of Saint Gall, and another from the Utrecht Psalter. Both show workmen sharpening and polishing swords in the final stages of production.

The major features of the longsword are the hilt and pommel, necessary to aid the grip and to keep the hand from slipping as the blade is swung and engaged with another blade or body. But far beyond utilitarian, hilts and pommels were often highly decorated and even embedded with jewels or other inlays.

Frankish sword pommels of the 8th century often featured lobes in a distinctive series of three or five. This design can typically be seen elsewhere in the manuscript art of the time, for example, the Lothar Gospels, Bern Psychomachia, Utrecht Psalter, and Stuttgart Psalter. This lobe style can also be seen on walls in church frescoes like that in Mals, South Tyrol, Italy.

Inlaid inscriptions were also a custom on Frankish blades from at least the reign of Charlemagne. The Ulfberht blades are some of the most notable. The trend continued through the high medieval period and was most popular in the 12th century. With the popularity of blade inscriptions, hilt decorations lost favor, and, particularly on Viking swords, hilts of the 10th century were typically plain steel.

Frankish longswords have been found all over Scandinavia and even as far east as Volga, Bulgaria. This wide distribution is indicative of just how important Frankish arms were as export trade goods and even valuable currency. This is despite the fact that Carolingian kings sought to curtail their export for fear of the swords’ falling into the hands of potential enemies. Charles the Bald, in 864 AD, actually imposed the death penalty on anyone selling Frankish longswords to Vikings. Nonetheless, Vikings were able to acquire them, as chronicled by Ibn Fadlan’s 10th century notes stating that Vikings in the Volga region were carrying Frankish blades.

During an 869 raid by Arab pirates on Camargue, in southern France, archbishop Rotland of Arles was taken captive, and his ransom was set at 150 swords.

Read another story from us: Kirkburn Sword: Possibly the best preserved Iron Age sword in Europe

While many sword specimens exist to this day, scabbards, which as we’ve seen were even more valuable than the steel, are almost never found intact. The wood and leather construction just doesn’t survive. But several illustrations provides us with some idea as to both their decoration and design. Contemporary manuscripts like the Stuttgart Psalter, Vivian Bible, and Utrecht show that a longsword was suspended from a sword-belt with two to three metal mounts.