In 1776, fifty-seven years after Daniel Defoe wrote Robinson Crusoe, eight people were rescued from a desert island in the Indian Ocean, where they had survived for fifteen years. S

even of the eight were women and were all former slaves. The eighth was a boy who had been born there.

Now, nearly 230 years later, archaeologists have uncovered the shameful history of their extraordinary ordeal. The team, hailing from France, had spent a month searching the wreck of the ship and excavating the treeless island.

The archaeological investigation was sponsored by UNESCO, as part of its year commemorating the struggle against slavery.

Their mission was to rediscover the almost-forgotten story of human’s cruelty against fellow humans. They did find that, but they also discovered a tale of human tenacity, determination to survive, and the ability to organize in the face of adversity.

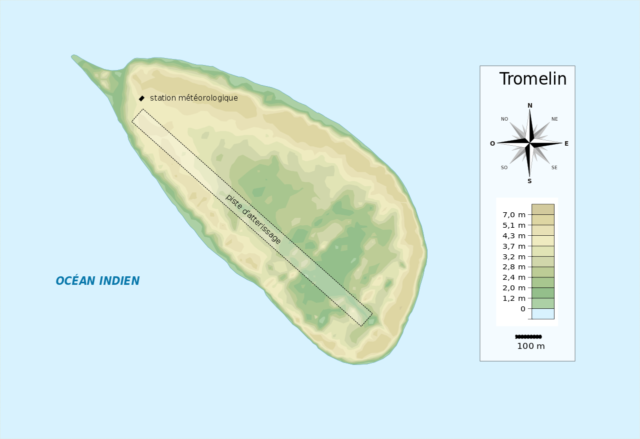

In July of 1761, a French ship foundered near the island of Tromelin, east of Madagascar. It carried an illicit cargo of slaves.

Twenty sailors drowned. So did seventy (or more) slaves, as they were unable to escape the flooding below deck—the hatches had been locked or nailed down.

The survivors, a group of about sixty people, made it to Tromelin Island, which is frequently wiped clean by typhoons. After six months on the island, the remaining sailors completed a seaworthy craft and escaped—the others were left on the island for a simple, brutal reason.

They were slaves. The nearest land was 300 miles away. The sailors did promise to return for those who remained, but it was a promise never fulfilled.

Despite this abandonment, the castaways didn’t give up. They kept the same signal fire going for all fifteen years, feeding it with driftwood and wood from the wreck.

They built houses from blocks of coral and impacted sand—the remains of which have been found by the archaeologists. Their diet consisted of turtles, seabirds, and shellfish that they cooked with the communal oven.

Thanks to the archaeological expedition, more information is now known about the castaways. According to Max Guérout, a marine archaeologist, former French naval officer, and leader of the expedition, “These were not people who were overwhelmed by their fate.

They were people who worked together successfully in an orderly way.” It was an elaborate, close-knit community that sprung up in the wake of the disaster. “We have found evidence of where they lived and what they ate. We have found copper cooking utensils, repaired, over and over again, which must originally have come from the wreck of the ship.”

He continued, “It is a very human story, a story of the ingenuity and instinct for survival of people who were abandoned because they were regarded by some of their fellow human beings as less than human.”

Aside from excavating the island, M. Guérout, who also founded the Groupe de Recherche en Archéologie Navale, followed a paper trail that lead through French and British archives of that period.

Among other things, he discovered a log book of the ship, Utile (Useful in French), that was wrecked on the island in 1761 with at least 150 illicit slaves on board.

Today, the island is claimed by both Madagascar and Mauritius, and since 1952, it has been the site of a French meteorological station. But back in 1761, the island was just an uncharted speck in the Indian Ocean.

In the year before the wreck, the Utile, which had served as a warship for France and was then owned by the East India Company, set sail from Bayonne, in southwest France. They were bound for Ile de France, or Mauritius, as it is now known.

At the time, France was engaged in the Seven Years’ War with Britain and the governor of Il de France was expecting an attack from India. So, he banned the import of slaves, fearing that they would be more mouths to feed in the event of a siege.

Regardless of this, the captain of the Utile dropped anchor at Madagascar and bought at least 150 Malagasy slaves.

Unfortunately for them, after the ship resumed its course eastwards, it was caught in a storm and ran aground on the submerged coral reef that breaks the surface as the island of Tromelin.

The shipwreck was documented in a terse, yet dramatic account by the ship’s official log keeper, Hilarion Dubuisson de Keraudic. This logbook would later be discovered by Guérout in the maritime archives at Lorient in Brittany.

“The coming of day and the sight of land, which diminished our terrors, reduced none of the furies of the sea. Several people threw themselves into the water with a line to try to reach the land, to no end.

A few reached the shore … We had to haul some others back over the debris, where they drowned. We were terrified all the while because the [shattered] stern of the ship, on which we were standing, opened and closed at each moment, cutting more than one person in two.” Hilarion wrote.

The logbook was full of details that would have otherwise been lost. For example, “All the remaining Gentlemen and crew were saved. Our losses were only 20 white men, and (two gentlemen) and many blacks, the hatches being closed or nailed down.”

Later, it is implied in the records that almost a third of the eighty-eight slaves who survived the initial wreck died, because the sailors kept the meagre water supplies to themselves. “We made a big tent with the main sail and some flags, and we (i.e., the gentlemen) lived there with all the supplies.

The crew were placed in small tents. We started to feel very strongly the shortage of water. A number of blacks died, not being given any.”

Eventually, the remaining 122 white men dug a well, which supplied fresh water, and after six months, they constructed a small sailing craft from the wreckage of the Utile.

Their craft was conveniently big enough to fit the white men, but not for the sixty remaining slaves. They left, leaving some food and a promise to return.

To their credit, when the Frenchmen reached Ile de France, they did try to keep their promise, according to the log book and other French records.

Sadly, the governor of the island, who was also an official of the French East India Company, didn’t want to risk the loss of another ship just to save a group of unwanted and illegal slaves.

This decision sparked a brief, public controversy in Ile de France. Despite the several local dignitaries who tried to persuade the governor to change his mind, he refused.

The former slaves had the well that they could use and some basic cooking implements. Luckily, the island was, and still is, a breeding ground for turtles and seabirds. M. Guérout, however, was determined to find out more.

His colleagues warned him that the thin soil and sand on the flat island was hardly likely to hold anything. The island also lies directly in the path of annual cyclones that sweep debris away.

Yet, Guérout has insisted that much must remain. So far, he has found intriguing references to visits to the island by Royal Navy vessels during the 19th century.

In these references, the British sailors recorded seeing the remnants of “stone” houses and neatly arranged graves.

When the team of ten French archaeologists and divers lived on the island from the 10th of October to the 9th of November of last year, they made several fascinating discoveries. Divers exploring the wreck found interesting objects, although none of these artifacts furthered the story.

The team has, however, uncovered the walls of elaborate dwellings that had been constructed from blocks of coral and from cement-like blocks of compacted sand. A large oven, with the remains of turtles, birds, and shellfish, was also found.

The copper cooking utensils found show signs of significant repairs over the years. One utensil had been repaired at least eight times. “They mended them with other pieces of copper, using hand-made copper rivets, forged in the fire of the oven. We even found some of the rivets,” Guérout noted.

The graves that were mentioned in the Royal Navy records remain elusive. “They are certainly still there,” Guérout said. “When we return next year, we will bring better digging equipment and we will find them.

Apart from anything else, the island provides us with a unique opportunity to study how a small group of people survived when plucked from their surroundings and left in hostile conditions.

Mankind has always been a migrant creature and the island can help us to study the human capacity for adaptation which makes migration possible.”

So, what happened to the eight known survivors on the island? Well, it appears that there were more than eight survivors—researchers guess that there were actually at least fourteen survivors, if not more.

In the French records that Guérout found, the women told their French rescuers that a group consisting of eighteen of the Malagasy castaways made a small sailing boat and left the island. It is not known whether they successfully reached land 300 miles to the west, or if they were lost at sea.

It appears that in 1776, a French sailor was shipwrecked on the island after he had attempted to rescue the castaways. With his help, a small craft was constructed.

Accompanied by three men and three women, he escaped to Mauritius. Soon after that, a rescue ship arrived, captained by a nobleman called Tromelin, whose name was then given to the island.

The final group of survivors was then removed. A family group of grandmother, mother, and child were some of the survivors.

By that time, a new governor was in office in Ile de France, who was more humane than his successor. He had been appointed by the King of France and had no connection with the French East India Company.

He insisted that the castaways were not slaves, but free people, since they had been bought illegally.

The family group of grandmother, mother, and child were then adopted by him, and the child was given the name Jacques Moise. Jacques was the governor’s own Christian name, and Moise is the French form of Moses—a baby rescued from the water.

What their fates were after that, the records do not say, although Guérout has searched the in France and Mauritius. He believes that the two groups of known survivors from Tromelin Island must have merged into the community of freed slaves in Mauritius, and their descendants are probably living there to this day.