A Kabuto is a helmet used by early Japanese warriors; it was an important part of the customary Japanese armor worn by samurai in Japan. These helmets were made of steel, iron, and, for the wealthiest, hammered copper. Occasionally, stiffened leather was used, and some of the helmets were lined with cloth for comfort.

The samurai were highly-skilled, elite soldiers emerging in about 900 AD during the Heian Dynasty. They were at their peak during the Edo period, beginning in 1603 and lasting until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa Ieyasu united Japan with social order, isolationism, and promotion of art and culture. The Tokugawa was the highest authority after the Emperor in Japan, and a former samurai himself. The word “samurai” has been interpreted by the leading translator of classic Samurai texts, William Scott Wilson, as “those who serve in close attendance to the nobility”.

In order to be chosen as a samurai, the soldier had to adhere to the Bushido philosophy – complete and absolute loyalty to one’s master. The warrior had to be ready to commit to years of training, including the development of strict self-discipline and willingness to sacrifice anything to demonstrate loyalty. Many began their training as children if their parents had been wealthy. If faced with a dishonorable death, a samurai would be expected to commit suicide in order to save face for himself or his master.

As they were at the top of the social order in society, samurai were held to extremely high standards and required to follow the teachings of Zen Buddhism. These soldiers were the only persons authorized to have a first and last name. Their swords, the wakizashi and the smaller daisho, represented social power and personal honor; only samurai could carry the two swords.

Important women could also be samurai and were educated in the martial arts. They did not serve in battle but were expected to defend their home and their master at all costs. Rather than swords, they usually carried daggers.

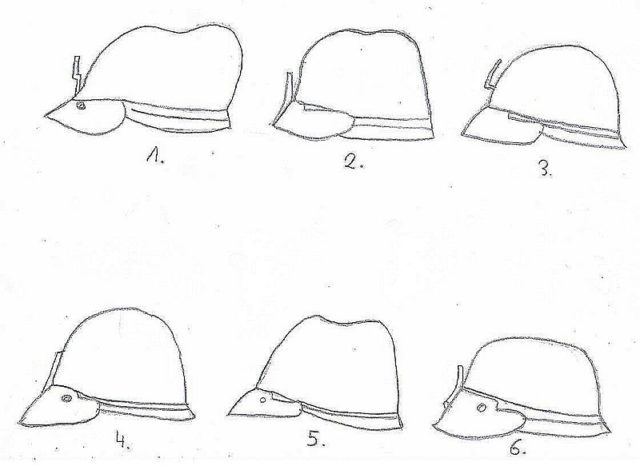

A typical kabuto consisted of a dome, the hachi, to which three to seven rows of metal plates were riveted together. The plates started from a small opening in the top, called the tehen, which was thought to accommodate the warrior’s top knot, or chomage, or else to provide ventilation.

Two helmet forms that did not have an opening at the top were the Zunari and Momonari kabutos. The rivets securing the metal plates to each other could be raised, hoshi-bachi, or hammered flat, suji-bachi. A form called hari bachi had the rivets filed down flush to the surface of the helmet. The finer hachi were invariably from one of several artisan families, the Myochin, Saotome, Haruta, or Unkai families.

The tehen was usually decorated with rings of elaborately worked, soft metal bands designed to resemble a chrysanthemum. A shikoro, or neck guard, was made from lacquered metal or ox hide held together by leather thongs or silk braids, but some had 100 or more small metal scales. The kabuto was secured to the head by a chin strap or silk cord called shinobi-no-o. Kabuto are often adorned with datemono, or crests – the maedate, or front decoration, wakidate the side decorations, kashiradate the top decoration, and ushirodate the rear decoration. Often they were family crests or sculptured objects representing animals, mythical entities, or other symbols. Horns were common, and many kabuto incorporated twin deer antlers and bull’s horns.

After the 1600s, helmets became much more elaborate. Made of papier mâché, wood, and lacquer, masks and maedate were created to resemble faces complete with mustaches, and beards, birds, statues of gods, fish, and mythical dragons.

Fortunately, enough of the helmets of early Japan have survived to allow people all over the world to see them and their accompanying armor in museums.

Writer: Donna Patterson