Since the formation of Saint Petersburg in 1703, the waterways in the Gulf of Finland were of strategic importance for Russia. Peter I initiated the construction of forts in the Gulf of Finland and directed the foundation of the first military installation on the island of Kotlin, Fort Kronshlot, in 1704. Throughout the following two centuries, Russia continued to fortify the area.

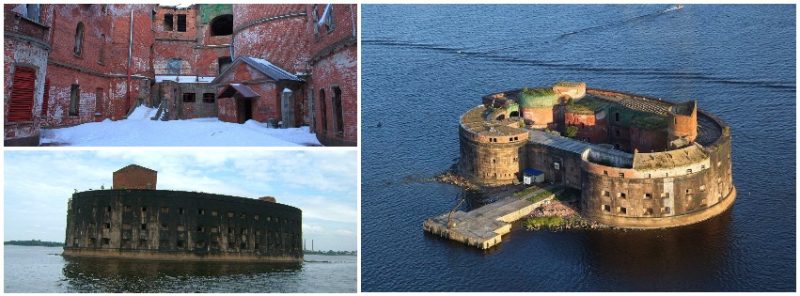

Louis Barthelemy Carbonnier d’Arsit de Gragnac (aka Lev Lvovich Carbonnier) drafted the initial blueprint for Fort Alexander. Earlier, he had planned the 1827 reconstruction of another military installation in the Gulf of Finland, Fort Citadel (later Fort Peter I). Upon Carbonnier’s death in 1836, Jean Antoine Maurice (aka Moris Gugovich Destrem), a Russian military engineer of French origin, revised the plan for a new fort. The construction began in 1838 and under the supervision of another Russian military engineer, Mikhail von der Veide. The builders drove 5535 piles, each 12-meters long, into the sea bed to reinforce the ground. They then covered the piles with a layer of sand, a layer of concrete blocks, and a layer of granite slabs. The brickwork of the fort received granite face-work. Emperor Nikolay I officially commissioned the fort on 27 July 1845; the fort was named to honor his brother, Emperor Alexander I.

The fort’s mission was to guard the Baltic waterway to Saint Petersburg south of naval base Kronstadt on Kotlin, in combination with Fort Peter I,Fort Risbank (later Fort Pavel I), Fort Kronshlot and the coastal battery Fort Constantin.

The fort never participated in any military action. Still, it played a role in the Crimean War when it protected the Russian naval base in Kronstadt against attempts by the Royal Navy and French fleets. Waters surrounding Fort Alexander and other Kronstadt fortifications witnessed the first ever deployment of galvanic naval mines designed by Moritz von Jacobi and chemical-contact naval mines developed by Immanuel Nobel. In June 1854, a squadron of the Royal Navy, under the command of Admiral Napier, approached the Kronstadt area, but evidence of mine fields and the heavy fortifications discouraged Napier from attacking Kronstadt. In the summer of 1855, an Anglo-French fleet under the command of Vice-Admiral Dundas tried to conduct minesweeping raids using small steamboats. British forces managed to raise several mines, at the cost of four vessels damaged or destroyed. Because the approach of the fleet within the range of the guns of coastal batteries and the forts would make sweeping procedures even more hazardous, Dundas gave up on his objective of attacking Kronstadt.

After 1855, Fort Alexander twice went on full alert: once in 1863, when a possible confrontation with British Empire was anticipated, and again during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). Upgrades to the fort were made in 1868–1869, 1867, and 1885. However, by the end of the 19th century, Fort Alexander was primarily used for ammunition storage, as the development of rifled artillery rendered the fort facilities, designed in an era ofsmoothbore guns, ineffective for defensive purposes. In 1896, Fort Alexander, Fort Peter I and Fort Pavel I were struck from the Russian military register.

In the 1890s, in wake of the discovery of the plague pathogen by Alexandre Yersin in 1894, the Russian government formed a special Commission on the Prevention of Plague Disease to facilitate research in this specific area of bacteriology. Fort Alexander’s isolation led the Commission to establish a new research laboratory there in January 1897. This laboratory was a part of Imperial Institute of Experimental Medicine (now Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences). Fort Alexander was renovated for the new purpose in 1897–1899, largely with funds from Duke Alexander Petrovich of Oldenburg, and featured a science library, research labs including containment labs, a stable for laboratory horses, cremation facility for lab animals, and other auxiliary facilities. Research work in Fort Alexander took off in August 1899 and was mainly focused on the study of plague disease and preparation of plague serum and vaccine from the immunized horses. In the following years, the laboratory is reported to have worked also on the development of serums against cholera, tetanus, typhus, scarlatina, and a series of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus infections. Work was hazardous and there were three pneumonic and bubonic plague cases among the staff members in 1904 and 1907 resulting in two fatalities. After the Communist takeover in 1917, the laboratory in Fort Alexander ceased operations.

After 1917, the fort was formally owned by Russian Navy, which maintained storage facilities and a repair shop there. By 1983, the fort was stripped of its fixtures and abandoned. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Fort Alexander was a popular location for rave parties. Since 2005 the fort was formally managed by the administration of the presidential conference center known as Constantine Palace in Strelna. The access inside the fort premises through the only gate of the fortress was secured since then.