Ambitious leaders tend to put forward ideas that not many around them would approve of. Nevertheless, this approval is usually not only unasked for, but rather dangerous. Joseph Stalin liked the idea of using forced labor in order to ‘catch up with and overtake the West’. Differing views would only end up increasing the population of labor camps.

During the 1930s, the Soviet government installed the Main administration of Soviet labor camps, colloquially known as the Gulag system. Some historians estimate that Gulag’s total population varied between half a million in 1934 and 1.7 million in 1953. In the aftermath of WWII, some four million Axis POWs were interned in those camps, but it was not for them that the gulag system was created.

The camps were initially formed for political prisoners, i.e. those who actively opposed the setting up of a new kind of state and society post-October revolution of 1917. After Stalin’s ascension to power, the criteria for sending people to camps drastically changed. They became the regime’s scarecrow.

You could be late to work, or a poor petty thief, stealing small quantities of food to feed your family, a foreign spy or soldier, or a dedicated Communist agitator who happened to disagree with a particular policy – either way, you’d be labeled an ‘enemy of the people’ and sent to rot in a distant and unwelcoming place, already swamped.

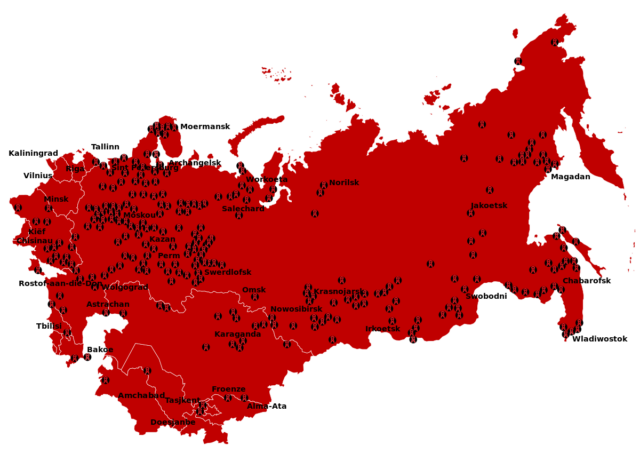

The camps differed in size, so the individual population of some 30,000 camps varied between 5,000 and 25,000 inmates. The sheer size of the Gulag system opened up the possibility of conducting gigantic infrastructural projects in this underdeveloped, post-war country. Enter forced labor.

Among the most notorious of those projects was the idea of the Salekhard–Igarka Railway, soon to become known as the Railroad of Death. The idea was to build a railroad that would connect Salekhard, the capital of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Region – and the closest town to the Polar circle – with Igarka, another small town in Krasnoyarsk Krai. The 1,300-kilometer railway would become part of the Transpolar Mainline, connecting Siberian east and west.

But the initial purpose of the project was to connect the nickel industry town of Norilsk with the to-be-built port in Salekhard, on the Ob River. After the river proved too shallow for any such endeavor, the new port was built in Igarka, and the decision was made to connect Salekhard and Igarka by a railway system, thus making it possible to link the area with the magnificent Trans-Siberian Railway at some point down the line.

In 1948, the project took off. It employed between 80,000 and 120,000 camp inmates. The huge gap in these figures testifies to the fact that almost no records were kept. The 501st Labor Camp started building the tracks from Salekhard, while the 503st Labor Camp was employed in Igarka. The working conditions were ruthless – blizzards and immense cold in winter, insects, pestilence and diseases in summer.

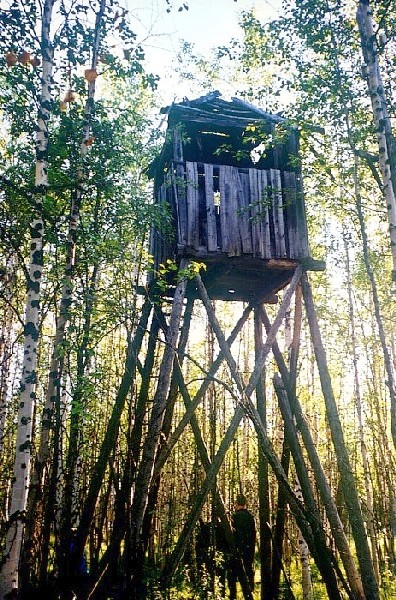

The terrain also proved to be unwelcoming. The construction was to be undertaken over permafrost. The lack of adequate machinery, supplies, and technical skill meant that everything built was far beyond the standard. The tracks ended up in bogs, the bridges burned and collapsed, while an immense number of forced laborers died. It is estimated that up to a third of workers lost their lives during this Siberian undertaking. Again, sloppy record keeping so the numbers are open to interpretation.

As the project dragged on, it became obvious that the need for such a railroad was not exactly rationally justifiable. The nickel industry that had during WWII moved to Siberia, was getting enough supplies from the south, while the very area in which the railroad was being built was so scarcely populated that it couldn’t generate enough demand. In the end, less than 700km of tracks laid, and the project was finally abandoned two weeks after Stalin’s death. The estimated cost of this endeavor totalled 42 billion rubles or $10 billion.

Nevertheless, parts of the railway remained in use for a few decades, and in 2010 220km of much of the original corridor was rebuilt to back the nickel and petroleum industry.