The infamous dictator was the target of numerous murder plots by political enemies, foreign governments, and former acolytes, many of which only missed out on changing history because of bad luck or poor timing. Learn the stories behind six assassins who nearly succeeded in killing Hitler.

1921: The Munich Beer Hall Melee

Assassination attempts on Hitler’s life began long before he ascended to political power. The first recorded attempt occurred in Munich in 1921.

In November of that year, Hitler spoke at a beer hall rally that was attended by a large audience, which included some three hundred people who were either member of opposition groups or otherwise violently hostile to him. The crowd included members of the Independent Socialist Party, the Majority Socialist Party, and the Communist Party.

Hitler’s speech “Who Are the Murderers?” was a vitriolic denunciation of the assassination on 25 October 1921, of Majority Socialist Reichstag Deputy Erhard Auer.

It was routine at such gatherings for the audience, both pro, and anti-speaker, to consume beer in inordinate quantities and to cache the empty Steins under the tables to use as ammunition in the inevitable melee. During Hitler’s speech, sharp remarks were exchanged between members of the gathering; this triggered first an avalanche of Steins, then the throwing of chairs, and finally a brawl that erupted throughout the hall.

Hitler was unhurt, however, and he even continued ranting for another 20 minutes until police arrived. Two years later, the nearby Bürgerbräukeller would be the site of the start of his infamous “Beer Hall Putsch,” a failed coup that won him national attention and a multi-year jail sentence.

1938: Maurice Bavaud’s Plot

Bavaud was a Catholic theology student, attending the Saint Ilan Seminary, Saint-Brieuc, Brittany, and a member of an anti-communist student group in France called Compagnie du Mystère.

The group’s leader, Marcel Gerbohay, had a lot of influence over Bavaud. Gerbohay claimed that he was a member of the Romanov Dynasty, and convinced Bavaud that when communism was destroyed, the Romanovs would once again rule Russia, in the person of Gerbohay.

Bavaud believed what Gerbohay and got convinced that the so-called “Führer” was a threat to the Catholic Church and an “incarnation of Satan,” and he considered it his spiritual duty to gun him down.

It began on the 9th November 1938 in Munich, few hours before the great anti-Jewish riots, called “Reichskristallnacht” by the Nazis.

Hitler marched at the top of his regime in the direction of “Feldherrnhalle”. Equipped with a pistol, which he hid in his coat pocket, Bavaud waited in the VIP lounge near the “Heiliggeistkirche”. When Hitler marched past him he tried to draw his pistol but was hampered by bystanders, who reached out their arms for the “Hitlergruss”.

Bavaud reluctantly gave up his hunt and was later arrested as he tried to stow away on a train out of Germany. When the Gestapo found his gun and maps, he confessed under interrogation to plotting to kill Hitler. In May 1941, he was executed by guillotine in Berlin’s Plötzensee Prison.

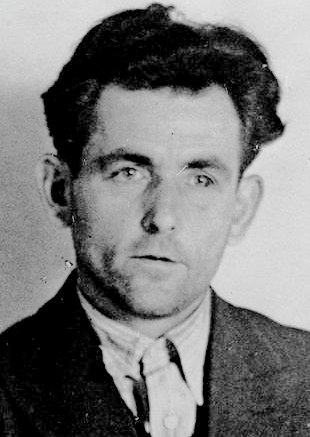

1939: Georg Elser’s Beer Hall Bomb

On 8 November 1939, Hitler was making his annual speech at a Munich beer hall. The event commemorated early Nazi struggles in the 1920s.

This time, Hitler used it to mock his international enemies and boast about Germany’s successful start to the war. But what neither Hitler nor the Nazi top brass and loyal audience realized was that, a few feet away from where the Fuehrer was standing, a bomb was about to go off .

Georg Elser was a struggling German carpenter and communist who was vehemently opposed to Nazism. He anticipated that Hitler’s regime would lead his country on the path toward war and financial ruin, and in late-1938, he resolved to do something about it.

Knowing that Hitler would speak at Munich’s Bürgerbräukeller brewery the following year on the anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, Elser spent several months building a bomb with a 144-hour timer. When his weapon was complete, he moved to Munich and began sneaking into the Bürgerbräukeller each night to hollow out a cavity in a stone pillar behind the speaker’s platform.

After several weeks of painstaking clandestine labor, Elser successfully installed his bomb. He set it to explode on November 8, 1939, at 9:20 p.m.—roughly midway through Hitler’s speech.

Hitler began this speech at the same time every year, but on this occasion, eager to return to Berlin and his military planners, the Fuehrer left early. Thirteen minutes later, the bomb exploded, causing eight deaths and massive damage. The ceiling collapsed just above where Hitler had been standing.

Elser was captured that same night while trying to steal across the Swiss border, and he later confessed after authorities found his bomb plans. He would spend the next several years confined to Nazi concentration camps. In April 1945, as the Third Reich crumbled, he was dragged from his cell and executed by the SS.

1943: Henning von Tresckow’s Brandy Bomb

Hermann Henning Karl Robert von Tresckow was an officer in the German Army who helped organize German resistance against Adolf Hitler. He attempted to assassinate Hitler in March 1943 and drafted the Valkyrie plan for a coup against the German government.

He was described by the Gestapo as the “prime mover” and the “evil spirit” behind the July 20 plot to assassinate Hitler.

Baron Henning von Tresckow, a staff officer, had sent two brandy bottles to a friend at Rastenburg – Major-General Helmuth Stieff. In fact, the bottles disguised a bomb. Stieff was a staff officer of the Army High Command at Rastenburg. He would have had the ability to put the bombs anywhere. The bomb failed to go off and Tresckow had to spend time retrieving them.

Tresckow and his co-conspirator Fabian von Schlabrendorff hoped Hitler’s death would be the catalyst for a planned coup against the Nazi high command, but their plan went up in smoke only a few hours later, when they received word that the Führer’s plane had landed safely in Berlin.

“We were stunned and could not imagine the cause of the failure,” Schlabrendorff later remembered. “Even worse would be the discovery of the bomb, which would unfailingly lead to our detection and the death of a wide circle of close collaborators.” Upon inspection, he found that a defective fuse was all that had prevented Hitler’s plane from being blown out of the sky.

1943: Rudolf von Gertsdorff’s Suicide Mission

Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff was an officer in the German Army. He attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler by a suicide bombing in March 1943; the plan failed when Hitler left early, but Gersdorff was undetected. That same month, soldiers from his unit discovered the mass graves of the Soviet-perpetrated Katyn massacre.

Only a week after Tresckow’s brandy bomb failed to explode, he and his co-conspirators made yet another attempt on Hitler’s life. This time, the scene of the assassination was an exhibition of captured Soviet flags and weaponry in Berlin, which the Führer was scheduled to visit for a tour.

After becoming close friends with leading Army Group Center conspirator Colonel (later Major-General) Henning von Tresckow, von Gersdorff agreed to join the conspiracy to kill Adolf Hitler.

After von Tresckow’s elaborate plan to assassinate Hitler on 13 March 1943 failed, von Gersdorff declared himself ready to give his life for Germany’s sake in an assassination attempt that would end with his own death.

“At this point, it became clear to me that an attack was only possible if I were to carry the explosives about my person,” he later wrote, “and blow myself up as close to Hitler as possible.” Gersdorff decided to proceed, and on March 21, he did his best to stay glued to the Führer’s side as he guided him through the exhibit.

The bomb had a short 10-minute fuse, but despite Gersdorff’s attempts to prolong the tour, Hitler slipped out a side door after only a few minutes. The would-be suicide bomber was forced to make a mad dash for the bathroom, where he defused the explosives with only seconds to spare.

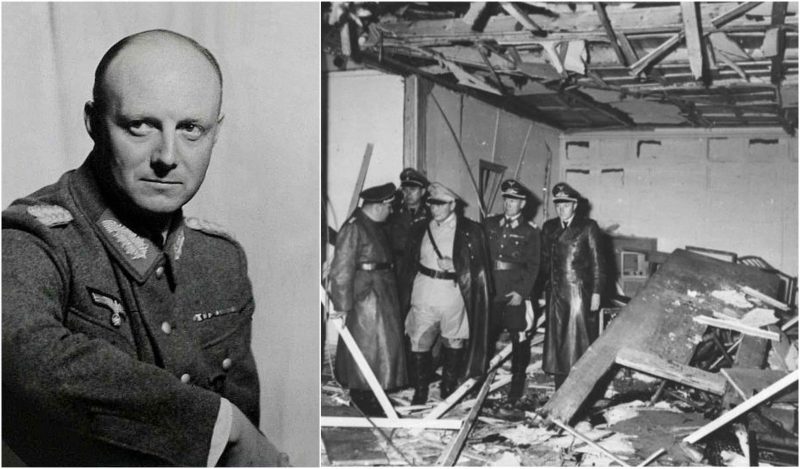

1944: The July Plot

The July Plot was an abortive attempt on July 20, 1944, by German military leaders to assassinate Adolf Hitler, seize control of the government, and seek more favorable peace terms from the Allies.

During 1943 and early 1944, opposition to Hitler in high army circles increased as Germany’s military situation deteriorated. Plans for the coup, code-named Walküre (“Valkyrie”), were set late in 1943, but Hitler, increasingly suspicious, became more difficult to access and often abruptly changed his schedule, thus thwarting a number of earlier attempts on his life.

At the center of the plot was Claus von Stauffenberg, a dashing colonel who had lost an eye and one of his hands during combat in North Africa, while the other leaders of the plot included retired colonel general Ludwig Beck (formerly chief of the general staff), Major General Henning von Tresckow, Colonel General Fridrich Olbricht and several other top officers.

Stauffenberg put the plan into action on July 20, 1944, after he and several other Nazi officials were called to a conference with Hitler at the Wolf’s Lair. He arrived carrying a briefcase stuffed with plastic explosives connected to an acid fuse. After placing his case as close to Hitler as possible, Stauffenberg left the room under the pretense of making a phone call.

His bomb detonated only minutes later, blowing apart a wooden table and reducing much of the conference room to charred rubble. Four men died, but Hitler escaped with non-life-threatening injuries — an officer had happened to move Stauffenberg’s briefcase behind a thick table leg seconds before the blast.

The planned revolt unraveled after news of the Führer’s survival reached the capital. Stauffenberg and the rest of the conspirators were all later rounded up and executed, as were hundreds of other dissidents. Hitler supposedly boasted that he was “immortal” after the July Plot’s failure, but he became increasingly reclusive in the months that followed and was rarely seen in public before his suicide on April 30, 1945.