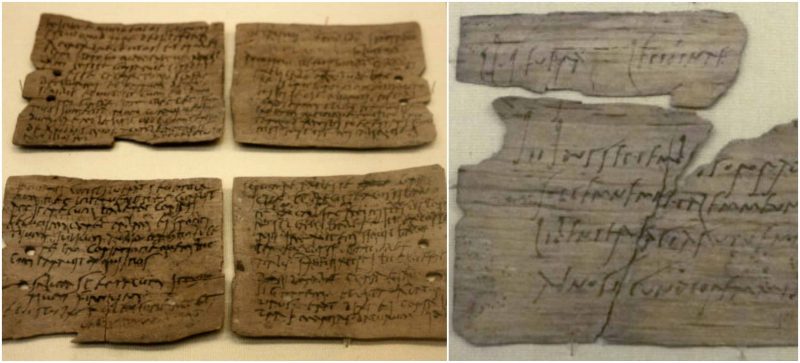

The Vindolanda tablets are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain. They are also probably the best source of information about life on the northern frontier of Roman Britain.Written on fragments of thin, post-card sized wooden leaf-tablets with carbon-based ink, the tablets date to the 1st and 2nd centuries AD (roughly contemporary with Hadrian’s Wall). Although similar records on papyrus were known from elsewhere in the Roman Empire, wooden tablets with ink text had not been recovered until 1973, when archaeologist Robin Birley discovered these artefacts at the site of a Roman fort in Vindolanda, northern England.

The documents record official military matters as well as personal messages to and from members of the garrison of Vindolanda, their families, and their slaves. Highlights of the tablets include an invitation to a birthday party held in about 100 AD, which is perhaps the oldest surviving document written in Latin by a woman. Held at the British Museum, the texts of 752 tablets have been transcribed, translated and published as of 2010. Tablets continue to be found at Vindolanda.

The wood tablets found at Vindolanda were the first known surviving examples of the use of ink letters in the Roman period. The use of ink tablets was documented in contemporary records andHerodian in the third century AD wrote “a writing-tablet of the kind that were made from lime-wood, cut into thin sheets and folded face-to-face by being bent”.

The Vindolanda tablets are made from birch, alder and oak that grew locally, in contrast to stylus tablets, another type of writing tablet used in Roman Britain, which were imported and made from non-native wood. The tablets are 0.25–3 mm thick with a typical size being 20 cm × 8 cm (7.9 in × 3.1 in) (the size of a modern postcard). They were scored down the middle and folded to form diptychswith ink writing on the inner faces, the ink being carbon, gum arabic and water. Nearly 500 tablets were excavated in the 1970s and 1980s.

First discovered in March 1973, the tablets were initially thought to be wood shavings until one of the excavators found two stuck together and peeled them apart to discover writing on the inside. They were taken to the epigraphist Richard Wright, but rapid oxygenation of the wood meant that they were black and unreadable by the time he was able to view them. They were sent to Alison Rutherford at Newcastle University Medical School for multi-spectrum photography, which led to infra-red photographs showing the scripts for researchers for the first time. The results were initially disappointing as the scripts were undecipherable. However, Alan Bowman at Manchester University and David Thomas at Durham University analysed the previously unknown form of cursive script and were able to produce transcriptions.

The tablets were produced in periods 2 and 3 (c. AD 92–103), with the majority written before AD 102. They were used for official notes about the Vindolanda camp business and personal affairs of the officers and households. The largest group is correspondence of Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the ninth cohort of Batavians and that of his wife, Sulpicia Lepidina. Some correspondence may relate to civilian traders and contractors; for example Octavian, the writer of Tablet 343, is an entrepreneur dealing in wheat, hides and sinews, but this does not prove him to be a civilian.

The best-known document is perhaps Tablet 291, written around AD 100 from Claudia Severa, the wife of the commander of a nearby fort, to Sulpicia Lepidina, inviting her to a birthday party. The invitation is one of the earliest known examples of writing in Latin by a woman. There are two handwriting styles in the tablet, with the majority of the text written in a professional hand (thought to be the household scribe) and with closing greetings personally added by Claudia Severa herself (on the lower right hand side of the tablet).

The tablets are written in Roman cursive script and throw light on the extent of literacy in Roman Britain. One of the tablets confirms that Roman soldiers wore underpants (subligaria),and also testifies to a high degree of literacy in the Roman army.

There are only scant references to the indigenous Britons. Until the discovery of the tablets, historians could only speculate on whether the Romans had a nickname for the Britons. Brittunculi(diminutive of Britto; hence ‘little Britons’), found on one of the Vindolanda tablets, is now known to be a derogatory, or patronising, term used by the Roman garrisons that were based in Northern Britain to describe the locals.

The tablets are written in forms of Roman cursive script, considered to be the forerunner of joined-up writing, which varies in style by author.With few exceptions, they have been classified as Old Roman Cursive.

The writing from Vindolanda appears as if it were written in a different alphabet to the Latin capitals used for inscriptions from other periods. The script is derived from the capital writing of the late first century BC and the first century AD. The text rarely shows the unusual or distorted letter-forms or the extravagant ligatures to be found in Greek papyri of the same period.Additional challenges for transcription are the use of abbreviations such as “h” for homines (men) or “cos” for consularis (consular), and the arbitrary division of words at the end of lines for space reasons such as epistulas(letters) being split between the “e” and the rest of the word.

The ink is often badly faded or survives as little more than a blur, so that in some instances transcription is not possible. In most cases the infra-red photographs provide a far more legible version of what was written than the original tablets. However, the photographs contain marks which appear similar to writing, but which certainly are not letters; additionally, they contain a great many lines, dots and other dark marks which may or may not be writing. Consequently, the published transcriptions have often had to be interpreted subjectively in deciding which marks should be regarded as writing.

The tablets are held at the British Museum, where a selection of them is on display in its Roman Britain gallery (Room 49).