It is a widespread belief that modern humans arrived in Europe about 45,000 years ago. What is not known is how they spread across the continent before the introduction of farming techniques.

Now, the most detailed genetic analysis to date has been carried out by researchers of Upper Paleolithic Europeans, and researchers have discovered a major new lineage of early modern humans.

This group is believed to have lived in northwest Europe about 35,000 years ago and have contributed directly to the ancestry of present-day Europeans. They are, essentially, the founding fathers of Europe.

Previous archaeological studies have found that modern humans swept into Europe 45,000 years ago — this is what ultimately led to the extinction of the Neanderthals, regardless of the fact that some modern humans interbred with them.

The Ice Age ended 12,000 years ago, and its peak was between 25,000 and 19,000 years. Before the world began to heat up, glaciers had covered Scandinavia and northern Europe, all the way to northern France. These regions that were once covered with ice became repopulated during the melt.

The team that is spearheading this research is led by David Reich. He and his colleagues hail from Harvard University. In order to study the repopulation of Europe, they have analyzed genome-wide data from fifty-one modern humans who lived between 45,000 and 7,000 years ago.

The genetic data shows that beginning 37,000 years ago, all Europeans come from a single population that persisted through the Ice Age. This founding group has deep branches all across Europe, one of which is represented by a specimen from Belgium. Many present-day Europeans can trace their ancestry all the way back to this group of humans.

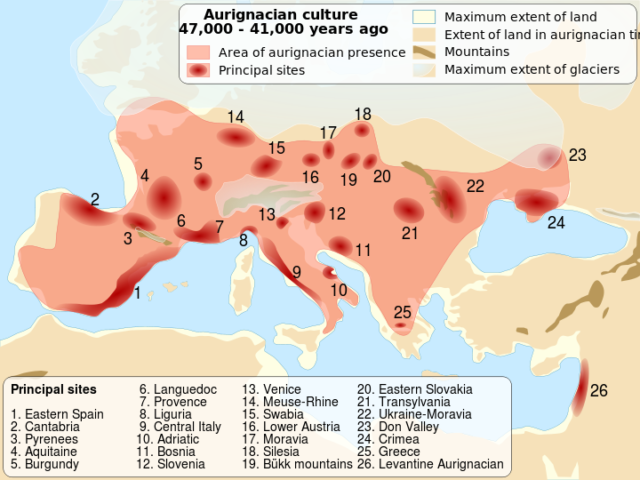

Things were not all calm for this founding population. This group is believed to have been part of the Aurignacian culture, and they became displaced when yet another group of early humans, called the Gravettian, arrived in Europe about 33,000 years ago. Then, the group related to the Aurignacian culture re-expanded across Europe around 19,000 years ago.

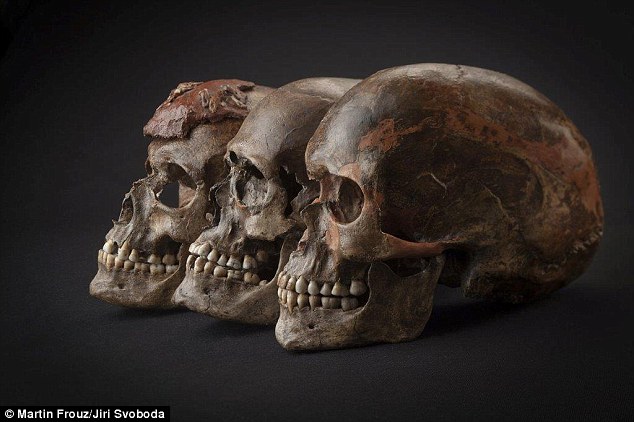

The evidence suggests that this re-expansion started from the southwest, present-day Spain. Remains found from this period include three 31,000-year-old skulls from Dolni Věstonice in the Czech Republic, the lower jaw of the 19,000-year-old ‘Red Lady of El Mirón Cave’ and the skull of a 14,000-year-old individual discovered at the Villabruna in northeastern Italy.

There was a second event that researchers detected. It happened around 14,000 years ago, when populations from the southeast, around Turkey and Greece, spread into Europe, displacing the first group of humans. Professor Reich added, “We see a new population turnover in Europe, and this time it seems to be from the east, not the west.”

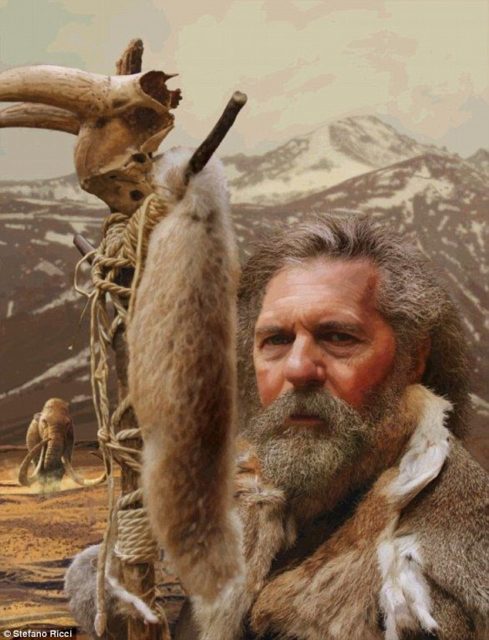

The Aurignacian culture thrived in Europe, as well as Southwest Asia, and dominated from 47,000 to 41,000 years ago, although they did emerge in smaller, scattered groups.

These people are linked with early cave art, including the animal engravings and imagery that are found in the Chauvet Cave in southern France. They made and used flint tools, such as blades and bladelets.

The Gravettians, on the other hand, were a Stone Age culture that was spread across much of Europe. This group of hunter-gatherers lived in Central and Eastern Europe between 30,000 and 20,000 years ago. One of the main staples of their diet were the large woolly mammoths.

Remains of this prehistoric culture have been found in caves in southern France and more open sites on the plains of Central Europe and Russia.

Professor Reich noted that “We see very different genetics spreading across Europe that displaces the people from the southwest who were there before. These people persisted for many thousands of years until the arrival of farming.”

Their study has been published in the journal, Nature, and has found that prehistoric human populations contained somewhere from three to six percent of Neanderthal DNA. Today, most humans only have about two percent.

“’Neanderthal DNA is slightly toxic to modern humans’ and this study provides evidence that natural selection is removing Neanderthal ancestry,” Professor Reich added.

There is a problem when examining ancient bones and DNA. The specimens that are used in such a study have frequently been contaminated with microbial DNA, as well as DNA from any archaeologist or lab technicians who have handled the remains.

To combat this problem, scientists have come up with a technique called “in-solution hybrid capture enrichment”. They used about 1.2 million 52-base-pair DNA sequences corresponding to positions in the human genome that they were interested in as bait to target specific segments of DNA. After they washed the ancient DNA over the 1.2 million probe sequences, the researchers then sequenced the ancient DNA that was captured by the probes.

Due to the fact that prior to the Harvard Medical School study there were only four samples of prehistoric European modern humans, aged 45,000 to 7,000 years old, that had available genomic data, the migration and evolution of human populations remained a mystery. Now, since new techniques have been developed, more samples can be accessed and analyzed.

“Trying to represent this vast period of European history with just four samples is like trying to summarize a movie with four still images.” Professor Reich explained, “With 51 samples, everything changes; we can follow the narrative arc; we get a vivid sense of the dynamic changes over time. And what we see is a population history that is no less complicated than that in the last 7,000 years, with multiple episodes of population replacement and immigration on a vast and dramatic scale, at a time when the climate was changing dramatically.”