King Island is a small island in the Bering Sea. It is situated just slightly west of Alaska, approximately 40 miles from Cape Douglas and some 90 miles from Nome.

The little island was first observed by Captain James Cook back in 1778, who named it after a member of his party, Lt. James King. It is uncertain how long this island had been inhabited, despite how impossible that might sound given the island’s situation.

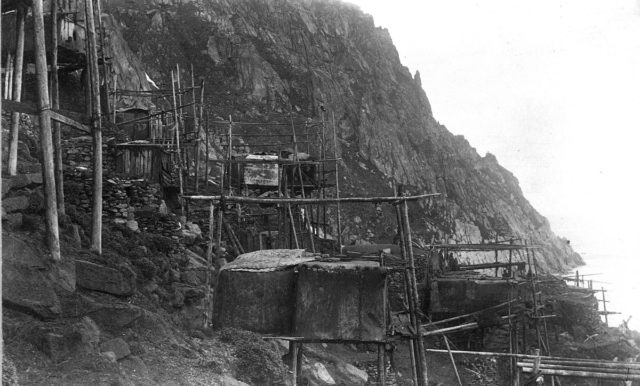

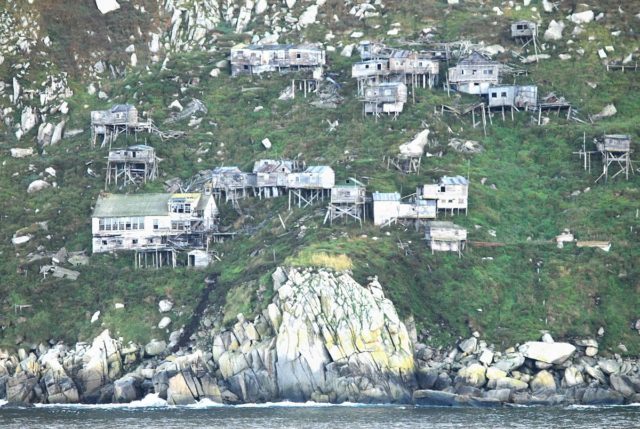

Dangerously steep rocky cliffs dominate its landscape, with the highest point reaching 700 feet while it’s only a mile in length. However, a slightly fragile-looking stilt village known as Ukivok had been built on the island. It used to be the winter seat of a native seafaring community, but it’s now been left abandoned for the last half a century.

The native Inupiat people who had overcome the challenge of inhabiting the steep slopes and cliffs of the island were no more than a community of 200. They called themselves Aseuluk, meaning “People of the Sea.” Another name they used was Ukivokmuit, formed from Ukivok, the village they built on King Island and “muit,” meaning “group of people.” The small village built on the slopes used a perilous arrangement of stilts and huts, but it was a home.

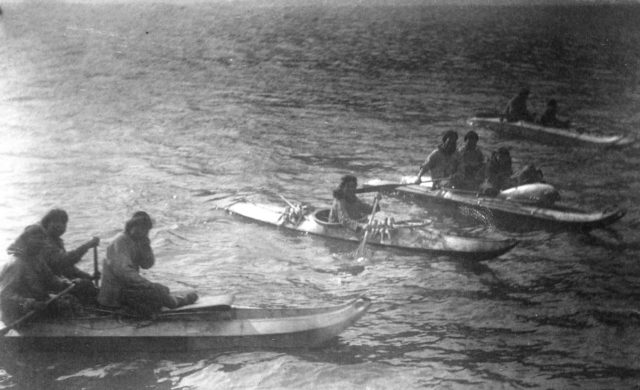

The natives lived mostly from hunting marine mammals such as seals and walruses throughout the summertime. They also gathered other food resources found on the mainland, while camping at locations near to present-day Nome, a city that is deemed to be one of the world’s largest gold pans. Crab fishing and collecting bird eggs were two of the other practices used for assuring there was enough food for everyone.

The summer and spring seasons were essential periods for gathering food for the Ukivokmuit. In winter, the hunting and fishing were still done on the ice, but as the daylight is limited in their part of the globe, they spent much of their time on activities such as dancing. Their dancing was done in the so-called “Qagri” (the men’s communal house). The month of December, for example, was known by the Ukivokmuit as “Sautugvik” or the time of drumming.

The nearby located Nome was founded only at the beginning of the 20th-century, and at one point it was the most populated city in Alaska. Slowly but steadily this city changed things around. At first, the Ukivokmuit maintained their tradition and camped near Nome each summer and engaged in trade by selling their authentic ivory carvings.

The real change occurred during the 1900s. At that point, the Bureau of Indian Affairs shut down the school on Ukivok, which caused the people to start abandoning the village. Reportedly, the village children were forcefully taken to school on mainland Alaska. Initially, this caused trouble regarding food security. In the absence of the youths, it was now down to the adults and elders to collect the much-needed food supplies for the winter. As they were left with little choice, the older people also migrated to the mainland to make a living.

By 1970, all King Island people had moved to Nome, and ever since the village of Ukivok has lain abandoned, decaying on the cliffs of the Island. Despite no longer living on their home island, the Ukivokmuit still preserve their cultural identity. In 2005 and 2006, the National Science Foundation funded a research project which allowed a few natives to go back to the island for the first time in some five decades. That must have been a strange experience in many ways.