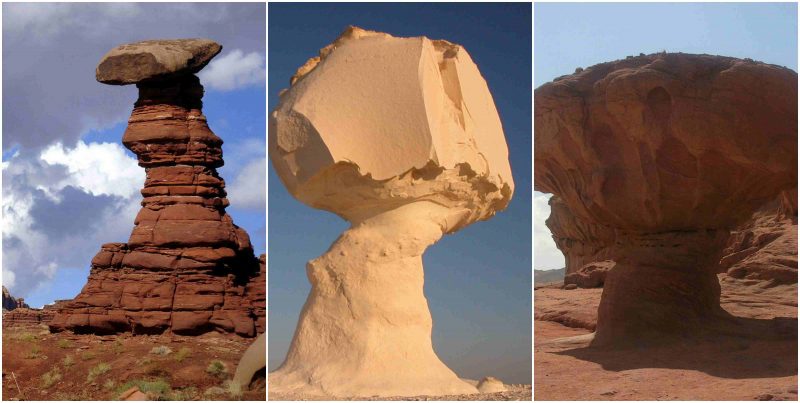

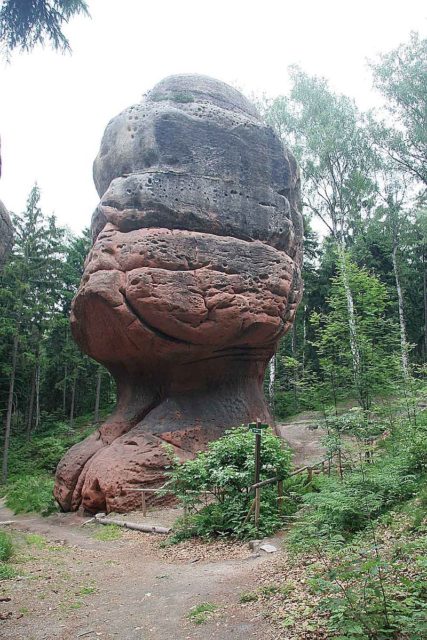

Large rock formations found in sandy areas all over the world, mushroom rocks seem to defy gravity. Also known as pedestal rocks, they take on this shape over thousands to millions of years. The rate of change is so slow that humans don’t even notice the difference; however, the formations will keep changing for as long as they stand.

That is, if people allow them to stand.

Mushroom rocks usually form in deserts, affected by varying factors such as wind and weathering, the chemical composition of the rock, and water or glacial activity. Sometimes, boulders fall and land on top of each other, forming a flat area of hard rock that covers a soft rock destined to erode more quickly.

Also, windblown sand is at its strongest at three feet off the ground, causing rock foundations to erode more rapidly than at their tops, such as in Timna Park, Israel, where there is a good example of this type of mushroom rock. Additionally, the upper part of the rock is chemically more resistant to erosion and weathering, and so it erodes more slowly than the base, resulting in the mushroom shape.

When one thinks of rock formations, the Middle Eastern deserts come to mind. In fact, the United States has more than its fair share: in Ellsworth County, Kansas, the Mushroom Rock State Park has mushroom rocks made from sandstone and sediments left on the outskirts of a Cretaceous sea over 100 million years ago. One formation has a diameter of 27 feet. Goblin Valley State Park near Green River, Utah, has mushroom rocks that resemble a crowd of people, or “goblins,” created by water and dust erosion. The Yellowstone River helped carve mushroom rocks at Makoshika State Park in Montana. A stout mushroom rock called Turnip Rock sits at the edge of Lake Huron in Port Austin, Michigan. This rock resembles a pirate ship that could be from Peter Pan’s Neverland, with a stand of 20-foot-tall trees and scrubby bushes growing on the top.

But mushroom rocks are not limited to the United States. On the coast of Barbados in Bathsheba, a volcanic mushroom rock sits in shallow water that at first glance looks like a straw hut. In the White Desert in western Egypt, an astonishing example of a mushroom rock is an enormous stone perched precariously on a tall base that leans like the Tower of Pisa.

Near the village of Oppedal in the municipality of Vågsøy in Norway, a large black mushroom rock protrudes from its base, resembling a whale’s tail. Mushroom and tortoise rocks are found among 75 other rock formations at the Tisa Walls rock formation in the Czech Republic.

Mushroom rocks are endangered most by human beings.

In September of 2016, a group of tourists destroyed a sandstone mushroom rock called the Duckbill in Cape Kiwanda, Oregon. At first, Oregon State Park workers thought it had collapsed on its own, but video footage from a drone operator was posted online showing the group pushing the rock over. The vandals have yet to be identified.

In October of 2013, two former Boy Scout leaders toppled a 20-million-year-old rock formation in Goblin Valley in less than a minute and posted a video of the destruction on Facebook. One was charged with one count of felony aiding and assisting in criminal mischief, and another with one count of felony criminal mischief. They both could be sentenced to up to five years in prison, but the district attorney wants to seek a plea deal. Facebook users were incensed, and some even sent death threats.

In both instances, the vandals claimed they were helping the community by removing the danger of the rocks toppling over and hurting someone.

Park officials and geologists’ response was that any rock could eventually fall, but no one had the right to topple them before their time. The Boy Scout Council of Utah removed the men from scouting permanently.