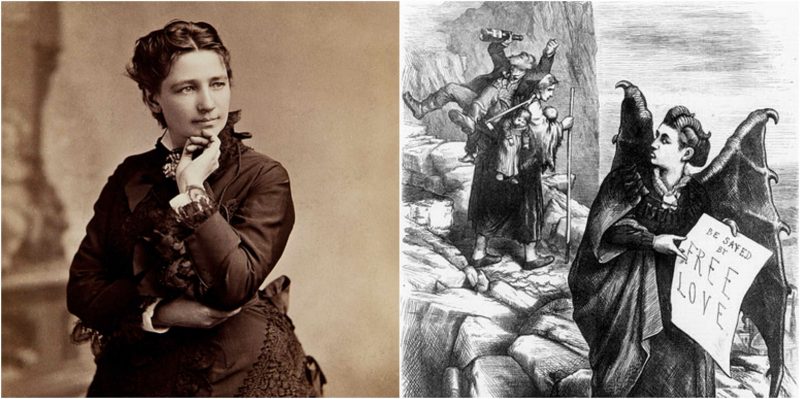

Above feminism, above courage, above intelligence is Victoria Woodhull.

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin was an American leader of the woman’s suffrage movement. In 1872, Woodhull was the first female to run for President of the United States.

An activist for women’s rights and labor reforms, Woodhull was also an advocate of free love, by which she meant the freedom to marry, divorce, and bear children without government interference.

Upon moving to New York City in 1868, Victoria and her sister, Tennessee began working as clairvoyants for the railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt, who distrusted medically trained doctors. During the 1869 gold panic, the sisters claimed to have netted around $700,000.

With Vanderbilt’s financial backing, Victoria and Tennessee then opened their own highly publicized firm named Woodhull, Claflin & Co., becoming the first female stockbrokers on Wall Street. Nonetheless, they never gained a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, something no woman would achieve until 1967.

Woodhull attended a female suffrage convention in January 1869 and became a devout believer in the cause. Women are citizens, she argued, and “the citizen who is taxed should also have a voice in the subject matter of taxation.” Although the committee rejected her petition to pass “enabling legislation,” her history-making appearance immediately propelled her into a leadership position among suffragists.

Woodhull was the first woman to run for president and she spent Election Day in jail

Woodhull ran under the banner of the Equal Rights Party, formerly the People’s Party, which supported equal rights for women and women’s suffrage. The party nominated her in May 1872 in New York City to run uphill against incumbent Republican Ulysses S. Grant and Democrat Horace Greeley and selected as her running mate Frederick Douglass, former escaped slave-turned-abolitionist writer and speaker.

On paper, it was an impressive pick, but not really: Douglass never appeared at the party’s nominating convention, never agreed to run with Woodhull, never participated in the campaign and actually gave stump speeches for Grant.

But that’s just one more of many caveats about Woodhull, who, throughout her long life never much cared for rules or regulations of a game she considered egregiously rigged against women.

Woodhull was furthermore hurt by embarrassing details about her private life, which came to light during a lawsuit that her mother brought against her second husband. In the end, Woodhull’s name appeared on ballots in at least some states. No one knows how many votes she received because they apparently weren’t counted.

A few days before the 1872 presidential election returned Grant to the office, Woodhull published an article in her newspaper aimed at exposing popular preacher Henry Ward Beecher as an adulterous hypocrite. The backlash was immediate, as Beecher’s supporters helped garner arrest warrants for Victoria and Tennessee on charges of sending obscene material through the mail.

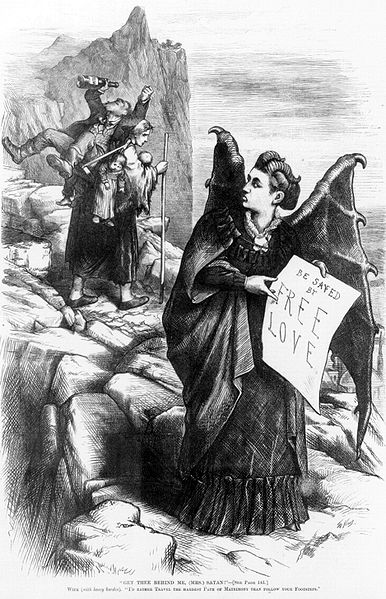

They also faced libel charges over a second article that accused a Wall Street trader of getting two teenage girls drunk and seducing them. Police took the sisters into custody on November 2, and they remained in jail for about a month. Additional arrests followed, including one after a briefly on-the-lam Woodhull snuck up on stage in disguise in order to give a speech. The sisters were eventually found not guilty, but not before taking a beating in the press. Their harshest critics included Harriet Beecher Stowe, Beecher’s sister and the author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” who called Woodhull a “vile jailbird” and an “impudent witch,” and cartoonist Thomas Nast, who depicted Woodhull as “Mrs. Satan.”

Woodhull was a proponent of free love

Woodhull often spoke about sex on the lecture circuit, saying, among other things, that women should have the right to escape bad marriages and control their own bodies. Even more shocking to Victorian sensibilities, she espoused free love.

“I want the love of you all, promiscuously,” she once declared. “It makes no difference who or what you are, old or young, black or white, pagan, Jew, or Christian, I want to love you all and be loved by you all, and I mean to have your love.” Woodhull practiced what she preached, at one point living with her ex-husband, her husband and her lover in the same apartment.

Yet she also knew when to hold back her amorous affections. “Let women issue a declaration of independence sexually, and absolutely refuse to cohabit with men until they are acknowledged as equals in everything, and the victory would be won in a single week,” she wrote.

Her opposition to abortion is frequently cited by opponents of abortion when writing about first wave feminism. The most common Woodhull quotations cited by opponents of abortion are:

- “the rights of children as individuals begin while yet they remain the fetus”

- “Every woman knows that if she were free, she would never bear an unwished-for child, nor think of murdering one before its birth.

One of her articles on abortion not often cited by opponents of abortion is from the September 23, 1871, issue of the Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. She wrote:

Abortion is only a symptom of a more deep-seated disorder of the social state. It cannot be put down by law…. Is there, then, no remedy for all this bad state of things? None, I solemnly believe; none, by means of repression and law. I believe there is no other remedy possible but freedom in the social sphere.

New life in England

In October 1876, Woodhull divorced her second husband, Colonel Blood. Less than a year later, exhausted and possibly depressed, she left to start a new life. When Commodore Vanderbilt died, his son William Henry Vanderbilt gave Victoria and Tennessee a large sum of money to leave the country and set up in England.

She made her first public appearance as a lecturer at St. James’s Hall in London on December 4, 1877. Her lecture was called The Human Body, the Temple of God, a lecture which she had previously presented in the United States. Present at one of her lectures was the banker John Biddulph Martin. They began to see each other and married on October 31, 1883. His family disapproved of the union but eventually gave in.

From then on, she was known as Victoria Woodhull Martin. Under that name, she published the magazine, The Humanitarian, from 1892 to 1901, with help from her daughter Zula Woodhull. After her husband died in 1901, Martin gave up publishing and retired to the country, establishing residence at Bredon’s Norton.

She died in England in 1927 at the age of 88.