When it was produced by the Dornier company of Germany in 1929, The Dornier Do X was the largest, heaviest, and most powerful flying boat in the world. First conceived by Dr. Claude Dornier in 1924, planning started in late 1925 and after over 240,000 work-hours it was completed in June 1929.

During the years between the two World Wars, only the Soviet Tupolev ANT-20 Maksim Gorki landplane of a few years later was physically larger, but at 53 metric tons maximum takeoff weight it was not as heavy as the Do X’s 56 tonnes.

The Do X was financed by the German Transport Ministry and in order to circumvent conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, which forbade any aircraft exceeding set speed and range limits to be built by Germany after World War I, a specially designed plant was built at Altenrhein, on the Swiss portion of Lake Constance.

The luxurious passenger accommodation approached the standards of transatlantic liners. There were three decks. On the main deck was a smoking room with its own wet bar, a dining salon, and seating for the 66 passengers which could also be converted to sleeping berths for night flights. Aft of the passenger spaces was an all-electric galley, lavatories, and cargo hold. The cockpit, navigational office, engine control and radio rooms were on the upper deck.

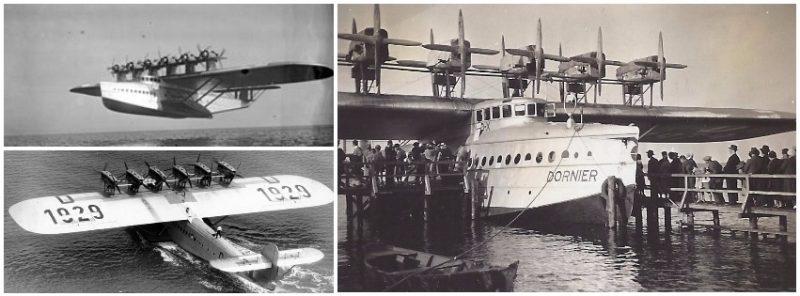

The lower deck held fuel tanks and nine watertight compartments, only seven of which were needed to provide full flotation. Similar to the later Boeing 314, the DO-X lacked conventional wing floats, instead using fuselage mounted “stub wings” to stabilize the craft in the water, which also doubled as an embarkation platform for passengers.

It was initially powered by twelve 391 kW (524 hp) Siemens-built Bristol Jupiter radial engines in tandem mountings (i.e. a “push-pull” configuration), with six tractor propellers and six pushers mounted in six strut-mounted nacelles above the wing. The nacelles were joined by an auxiliary wing whose purpose was to stabilize the mountings. The air-cooled Jupiter engines were prone to overheating and could barely lift the Do X to an altitude of 425 m (1,400 ft). The engines were supervised by a flight engineer, who also controlled the 12 throttles and monitored the 12 sets of engine gauges.

The pilot would ask the engineer to adjust the power setting, in a manner similar to the system used on maritime vessels, i.e. an engine order telegraph. Indeed, many aspects of the aircraft echoed nautical arrangements of the time, including the flight deck, which bore a strong resemblance to bridge of a vessel. After completing 103 flights in 1930, the Do X was refitted with 610 hp Curtiss V-1570 “Conqueror” water-cooled V-12 Vee engine. Only then was it able to reach the altitude of 1,650 ft necessary to cross the Atlantic.

Germany’s original Do X was turned over to Deutsche Luft Hansa, the national airline at that time, after the financially strapped Dornier Company could no longer operate it. After a successful 1932 tour of German coastal cities, Luft Hansa planned a Do X flight to Vienna, Budapest, and Istanbul for 1933. The voyage ended after nine days when the flying boat’s tail section tore off during a botched, over-steep landing on a reservoir lake near the city of Passau.

While the fiasco was successfully covered up, the Do X was out of service for three years, during which time it changed hands several times before reappearing in 1936 in Berlin, Hormann writes “Am 5.September 1933 flog Chefeinflieger Wagner die DO-X zum Bodensee zurück. Mit dem Fiasko von Passau begann für DO-X der Weg ins Museum.” (“On 5 September 1933 chief test pilot Wagner flew the DO-X back to the Bodensee (Lake Constance). The Passau fiasco started the DO-X’s trip to the museum.”) The Do X then became the centerpiece of Germany’s new aviation museum Deutsche Luftfahrt-Sammlung at Lehrter Bahnhof.

The Do X remained an exhibit until it was destroyed in an RAF air raid during World War II on the night of 23–24 November 1943. Fragments of the torn-off tail section are on display at the Dornier Museum in Friedrichshafen. While never a commercial success, the Dornier Do X was the largest heavier-than-air aircraft of its time, a pioneer in demonstrating the potential of an international passenger air service. A successor, the Do-20, was envisioned by Dornier, but never advanced beyond the design study stage.