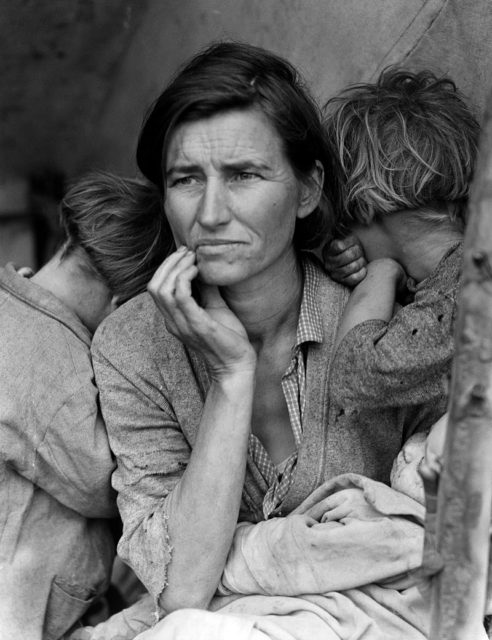

“Migrant Mother,” 1936, California

The photograph that has become known as “Migrant Mother” is one of a series of photographs that Dorothea Lange made of Florence Owens Thompson and her children in February or March of 1936 in Nipomo, California. Lange was concluding a month’s trip photographing migratory farm labor around the state for what was then the Resettlement Administration. In 1960, Lange gave this account of the experience:

I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean- to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it. (From – Popular Photography, Feb. 1960).

Lange’s photo became a defining image of the Great Depression, but the migrant mother’s identity remained a mystery to the public for decades because Lange hadn’t asked her name. In the late 1970s, a reporter tracked down Owens (whose last name was then Thompson), at her Modesto, California, home.

Thompson claimed that Lange never asked her any questions and got many of the details incorrect. Troy Owens recounted:

“There’s no way we sold our tires because we didn’t have any to sell. The only ones we had were on the Hudson and we drove off in them. I don’t believe Dorothea Lange was lying, I just think she had one story mixed up with another. Or she was borrowing to fill in what she didn’t have.”

Thompson was critical of Lange, who died in 1965, stating she felt exploited by the photo and wished it hadn’t been taken and also expressing regret she hadn’t made any money from it. Thompson died at age 80 in 1983. In 1998, a print of the image, signed by Lange, sold for $244,500 at auction.

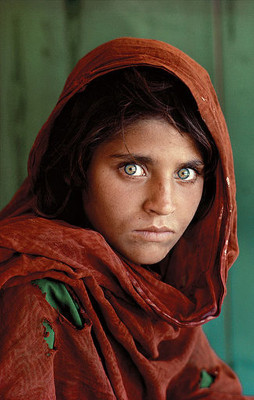

“Afghan Girl”, 1984, Pakistan

Afghan Girl is a 1984 photographic portrait by journalist Steve McCurry which appeared on the June 1985 cover of National Geographic. It is an image of a young woman with green eyes in a red headscarf looking intensely at the camera. It has been likened to Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of the Mona Lisa and has been called “the First World’s Third World Mona Lisa“. The image became “emblematic” of “refugee girl/woman located in some distant camp” deserving of the compassion of the Western viewer.

McCurry took his most recognized portrait, “Afghan Girl”, in December 1984 of an approximately 12-year-old Pashtun orphan in the Nasir Bagh refugee camp near Peshawar, Pakistan. The image itself was named as “the most recognized photograph” in the history of the National Geographic magazine and her face became famous as the cover photograph on the June 1985 issue.

The photo has also been widely used on Amnesty International brochures, posters, and calendars. The identity of the “Afghan Girl” remained unknown for over 17 years until McCurry and a National Geographic team located the woman, Sharbat Gula, in 2002. McCurry said, “Her skin is weathered; there are wrinkles now, but she is as striking as she was all those years ago.”

Pashtun by ethnicity, Gula’s parents were killed during the Soviet Union’s bombing of Afganistan when she was around six years old. Along with her grandmother, brother, and three sisters, she walked across the mountains to Pakistan and ended up in the Nasir Bagh refugee camp in Pakistan in 1984.

She married Rahmat Gul between the age of 13-16 and returned to her village in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s. Gula has three daughters. A fourth daughter died in infancy. She expressed hopes that her children will be able to get an education.

A devout Muslim, Gula normally would wear a burka and was hesitant to meet with McCurry, as he was a male from outside the family. When asked if she had ever felt safe, she responded “No. But life under the Taliban was better. At least there was peace and order.” Until the National Geographic team found her again, she had never seen the photo of herself as a child. When asked how she had survived, she responded that it was “the will of God”

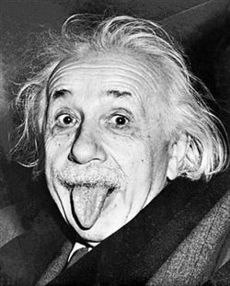

Albert Einstein, 1951, New Jersey

On March 14, 1951, photographer Arthur Sasse captured this image of Einstein leaving a 72nd birthday celebration held in his honor in Princeton, New Jersey. At the time the photo was taken, Sasse had been attempting to get the Nobel Prize-winning physicist to smile, but instead he stuck out his tongue as he sat in the back seat of a car. As it turned out, Einstein liked the shot so much he had some prints made for himself.

The German-born Einstein, who became a U.S. citizen in 1940, died four years after Sasse snapped his famous photo. In 2009, an original print signed by the renowned scientist sold at auction for more than $74,000. In 1953, in the midst of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade, Einstein had given the print to outspoken journalist Howard K. Smith, with the inscription (translated from German): “This gesture you will like, because it is aimed at all of the humanity. A civilian can afford to do what no diplomat would dare. Your loyal and grateful listener, A. Einstein.” Einstein spoke out against McCarthyism, and historians have said the gesture in the photo and its inscription represent his spirit of non-conformity.

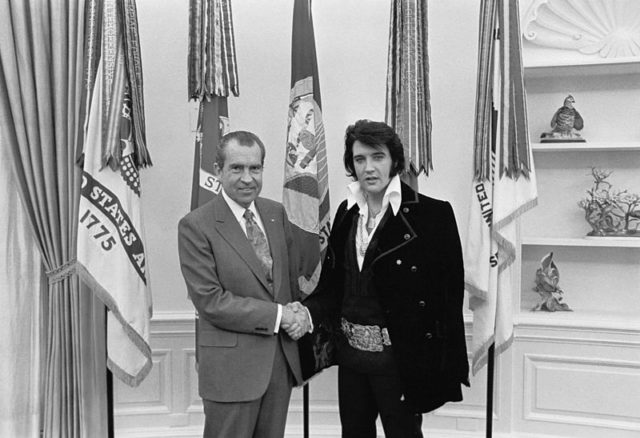

Richard Nixon & Elvis Presley, 1970, White House

Copies of this photo are requested from the National Archives more than any other image. Source

One of the most popular photographs at the National Archives is an image of two famous men. They’re not doing much, really—just standing there, clasping hands, smiling for the camera.

One day in 1970, Elvis Presley showed up at the northwest gate of the White House, bearing a five-page letter that he’d written on American Airlines stationery. “Dear Mr. President,” it began. “First, I would like to introduce myself. I am Elvis Presley and admire you and have great respect for your office.”

The letter went on to describe Presley’s concern about the problems facing the country (“the drug culture, the hippie elements . . . “) and his interest in helping out—which he felt would require credentials as a “Federal Agent at Large.” He concluded, “I would love to meet you just to say hello if you’re not too busy.”

Elvis wrote to the president on American Airlines stationery while onboard a flight to Washington, D.C. After landing, he hand-delivered the letter to a guard at the White House gate. Elvis had served his country once before when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1957.

This time, he wanted to become an undercover agent in the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, a desire the film never explains. Elvis’s wife Priscilla later claimed that her husband thought credentials from the agency would allow him to carry guns and drugs wherever he went.

President Richard M. Nixon’s appointments secretary drew up a memo recommending the meeting. “You must be kidding,” wrote Nixon’s chief of staff in the margin of the memo. Nonetheless, a meeting was arranged, and it was photographed by White House photographer Ollie Atkins.

In 1975, the photographs—along with other official records of the Nixon presidency—were transferred to NARA, where they came under the jurisdiction of the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff. In the early 1980s, the photographs were part of a set of materials that were opened for public research.

“The Situation Room,” 2011, White House

Taken on the afternoon of May 1, 2011, this image shows President Barack Obama and his national security team receiving updates about the top-secret Navy SEAL raid on the Pakistani compound of one of the most-wanted men in U.S. history, al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. At 11:35 ET that night, the president appeared on live TV to announce that the mastermind behind the 9/11 terrorist attacks had been killed by the SEALs.

White House photographer Pete Souza snapped the photo after Obama and his senior aides had crowded into a small conference room in the West Wing’s Situation Room complex, where Brigadier General Marshall “Brad” Webb was monitoring the mission. When Obama entered the room, Webb offered the president his chair. However, as Obama told NBC News, “ I said, ‘You don’t worry about it.

You just focus on what you’re doing. I’m sure we can find a chair and I’ll sit right next to him.’ And that’s how I ended up [on a] folding chair.” Obama later referred to the high-stakes raid, during which a SEAL helicopter crash-landed at bin Laden’s hideout, as the longest 40 minutes of his life, while Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said she’d been concentrating so intensely while monitoring the raid that she hadn’t been aware the White House photographer was taking pictures.