A tale found in 18th century English folklore, deeply carved into the very roots of popular culture, tells of three little pigs and the manner in which each dealt with the outside threat of the big bad wolf.

The first little piggy, merry as he undoubtedly was, built himself a house out of straw, leaving time for fun and play. The second pig made his home out of sticks, taking a little longer in the process, yet still left time for life’s enjoyments. Meanwhile, the last little pig put in some extra effort after having learned enough about the threat at hand, and built himself a house of bricks and sand.

A poetic story with an ending most of us are familiar with, it represents a lesson that hard work and dedication result in success, and it pays to plan ahead and not take shortcuts. Except for, of course, when the shortcut is indeed the plan itself, or as Sam Ewing, a former baseball player for the Chicago White Sox, once put it, “it’s not the hours you put in your work that counts, it’s the work you put in the hours.” For it was not the walls of bricks and stones that stopped the big bad wolf, but the preparation and initiative to set up a trap on the inside that overcame the threat.

Reflecting on this, we are reminded of a civilization of master craftsmen, mankind’s greatest shipbuilders, who fully understood what their outer threats were. Doing what they did best, they used some of their astounding knowledge and found a shortcut, building homes and precious shrines exactly as they built their ships. Between the 11th and 13th century, instead of using steel and stone, the Nords built thousands and thousands of churches entirely out of wood. They were, in fact, the first to do that, in contrast to popular belief, and some, having endured the test of time, still stand precisely as they were built more than eight centuries ago.

Ancient Northmen, considered among the best craftsmen in wood due to the large forests they had to work with, had a tradition of using wood in almost all aspects of their lives. They used it to such an extent that this practice led to development of a distinctive technique, one that allowed for the construction of powerful ships, the ones for which Vikings are best remembered.

Seeing their ships withstand the wrath of the ocean, Nords used the same woodworking expertise that made them such skilled shipbuilders to construct churches during the Middle Ages, when Christianity spread worldwide. Despite the fact that utilizing stone would be more logical, they knew that raising stone buildings was unnecessary in a land where the sun is rare and flames even fewer, or where foreign invaders rarely ever set foot.

CC BY-SA 2.5

Consequently, the Vikings built shrines as they would a ship, knowing for sure they could resist the only plausible threat: nature itself. Rain, snow, and blasting winds were nothing compared to an angry ocean, no matter how hard a land storm might huff and puff.

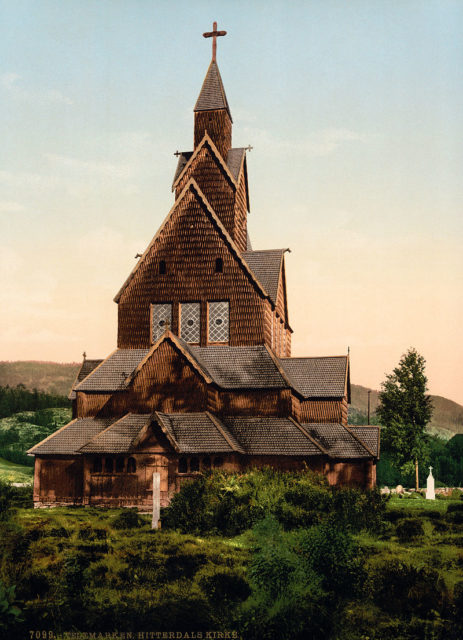

It is estimated that between the 10th and 11th centuries, when Norway shifted to Christianity, Nords built thousands of these and they were known as Stavkirke chapels, or Stave churches. They were built out of a particular kind of fir, the “malmfuru.” Now a sadly extinct evergreen coniferous tree, one that grew extremely large in size, it had a straight trunk and was tough and flexible at the same time, thus allowing for expertly crafted joints, strong beams, and large pillars.

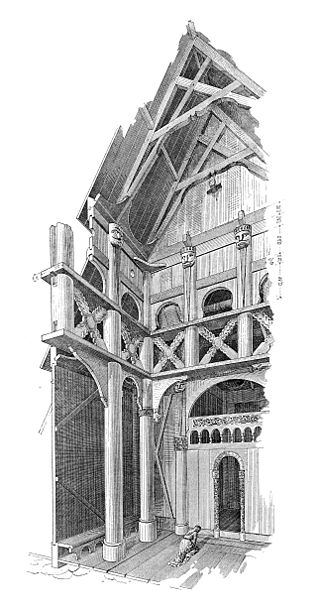

Many architects who have studied the remaining examples found the large pillars (staves) placed in such a complex manner that they consider it a miracle of engineering. Furthermore, the walls of the stave churches were composed of huge vertical planks, reinforced with four extra beams so that they could hold up the roof.

Atop of that, another smaller roof is raised, and another one on that, up until the last one, which is a narrow, pointy roof built as if it is reaching toward the sky. Upon each roof, additional beams and staves are placed in order to support it. When compared to the nearest living specimen to the tree they used most, the Douglas fir, it looks as if the Norwegians built churches almost identical to the tree itself.

Indeed, all of it, no matter how strange it might seem, was accomplished by utilizing wood only. The only piece of metal found is that of the door locks. Where nails were deemed necessary, the Nords would apply dowel pins also made out of wood, and this is what many consider to be the sole reason why some of the churches have survived for so many years.

As some of the architects who investigate the churches over the years unanimously conclude, if utilized dowels are made out of wood, they provide breathing space for a structure during seasonal changes. Simply put, a composition made out of wood could expand and contract along with nature.

If there is a shift outside, for instance, in temperature or humidity, the structure goes along with it, instead of being locked rigidly in place by iron. This also gave the structure a huge amount of elasticity. What’s more, the buildings would be placed on top of a massive foundation of flat stones, utilized in order to raise the foundation beams from the ground, thus keeping the structure safe from ground moisture and rotting.

Nowadays, there are only 28 left of the thousands built during the Middle Ages. One of the best examples of this unparalleled building technique is the Borgund stave church, frequently visited, which was built at the very end of the 12th century in devotion to the Apostle Andrew. Located deep in Sognefjord, the largest fjord in Norway, this church seems almost untouched.

Whereas in the past, foreigners almost never set foot in the North, using public transportation, Norway is accessible for anyone willing and curious. With public buses and usable roads built across Filefjell, everyone can see the Borgund stave church for themselves.